By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets Live commentator and reporter

China’s vulnerability to a heavy private-debt load and the collapsing real-estate market increase the risk that the PBOC allows the yuan to weaken further, or that the fixed exchange-rate system with the dollar is dropped altogether.

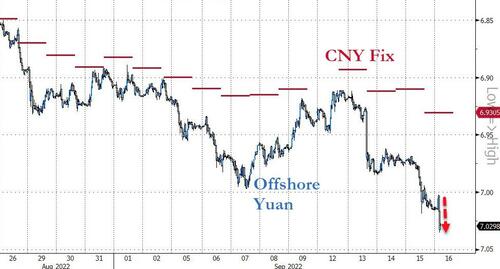

The dollar is rallying again today, putting pressure on currencies around the world. Of significance, the yuan has breached the widely-watched level of 7 for the first time since 2020.

China has started to push back more heavily against the weakening, with the official yuan fix moving from about 400 pips lower than USD/CNY at last week to 845 pips today.

The PBoC also withdrew yuan liquidity from the market Thursday, as well as last week announcing a reduction in the FX reserve ratio for banks due to take effect today.

But it is getting harder for China to keep gravity at bay for the yuan.

China’s growth model of subsidizing the export-facing state-owned enterprise sector by repressing the household one – a policy reinforced by the pandemic – means that China’s ballooning trade surplus is a sign of weakness, not strength.

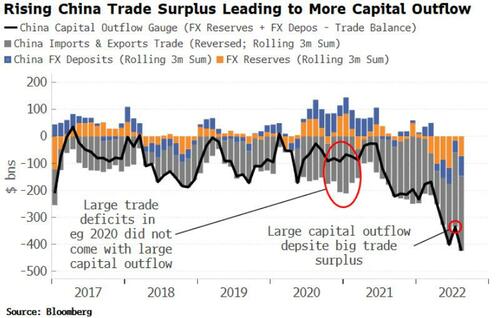

In a nominally closed capital-account country, a proxy for capital outflow is given by the difference between FX reserves and the trade surplus. If such a vast surplus was good for growth, we would expect to see FX reserves and deposits rise (even taking account of dollar-devaluation effects to existing reserves).

Instead, both are falling, highlighting that the trade surpluses are triggering a growth slowdown and net capital flight.

This puts pressure on the yuan.

Some of the weakening has been sanctioned by the Chinese authorities, easing some of the negative growth impact from capital outflow. But it is clear they are now trying to push back against the yuan’s decline.

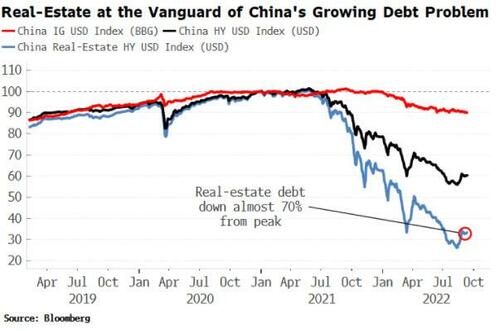

The problem is compounded by the collapse in the real-estate sector. The debt of real-estate companies is down over 60% from last year’s peak. Overall, China has seen a rapid rise in debt over the last ten years, with the cost of servicing it increasing to over 20%, a level that has previously triggered debt crises in other countries.

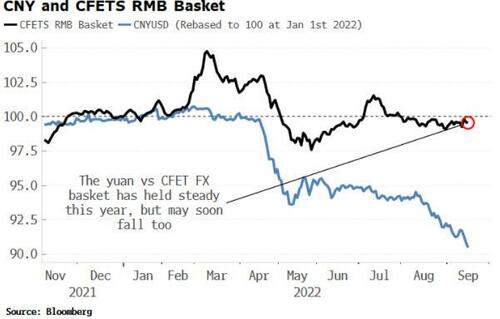

Also, while the yuan has weakened mostly against the dollar, it has actually strengthened against two of China’s largest trade competitors, Japan and Korea. We may therefore soon see the yuan’s weakness becoming more broad-based, and it also falling against the CFETS FX basket, which has held remarkable steady so far.

To try to avoid a debt-triggered crisis, one lever China can pull is allowing the yuan to weaken further, or even dropping the fixed exchange-rate altogether.

It is one way to stave off the greater evil of widespread unemployment and civil unrest, dangers China could well face if growth continues to fall.

By Simon White, Bloomberg Markets Live commentator and reporter

China’s vulnerability to a heavy private-debt load and the collapsing real-estate market increase the risk that the PBOC allows the yuan to weaken further, or that the fixed exchange-rate system with the dollar is dropped altogether.

The dollar is rallying again today, putting pressure on currencies around the world. Of significance, the yuan has breached the widely-watched level of 7 for the first time since 2020.

China has started to push back more heavily against the weakening, with the official yuan fix moving from about 400 pips lower than USD/CNY at last week to 845 pips today.

The PBoC also withdrew yuan liquidity from the market Thursday, as well as last week announcing a reduction in the FX reserve ratio for banks due to take effect today.

But it is getting harder for China to keep gravity at bay for the yuan.

China’s growth model of subsidizing the export-facing state-owned enterprise sector by repressing the household one – a policy reinforced by the pandemic – means that China’s ballooning trade surplus is a sign of weakness, not strength.

In a nominally closed capital-account country, a proxy for capital outflow is given by the difference between FX reserves and the trade surplus. If such a vast surplus was good for growth, we would expect to see FX reserves and deposits rise (even taking account of dollar-devaluation effects to existing reserves).

Instead, both are falling, highlighting that the trade surpluses are triggering a growth slowdown and net capital flight.

This puts pressure on the yuan.

Some of the weakening has been sanctioned by the Chinese authorities, easing some of the negative growth impact from capital outflow. But it is clear they are now trying to push back against the yuan’s decline.

The problem is compounded by the collapse in the real-estate sector. The debt of real-estate companies is down over 60% from last year’s peak. Overall, China has seen a rapid rise in debt over the last ten years, with the cost of servicing it increasing to over 20%, a level that has previously triggered debt crises in other countries.

Also, while the yuan has weakened mostly against the dollar, it has actually strengthened against two of China’s largest trade competitors, Japan and Korea. We may therefore soon see the yuan’s weakness becoming more broad-based, and it also falling against the CFETS FX basket, which has held remarkable steady so far.

To try to avoid a debt-triggered crisis, one lever China can pull is allowing the yuan to weaken further, or even dropping the fixed exchange-rate altogether.

It is one way to stave off the greater evil of widespread unemployment and civil unrest, dangers China could well face if growth continues to fall.