Indian farmer protests restarted in early 2024 as talks on the producers' demands to set more legally binding minimum support prices for agricultural products have broken down.

The borders of city state and capital Delhi have been fortified but farmers from surrounding areas seem determined to push past the barricades this week armed with heavy equipment, supplies and masks to fend off tear gas deployed by police. Ahead of the presidential elections in April and May, farmers once again want to make their grievances heard. Similar protests rocked India previously in 2020 and 2021 as farmers vehemently opposed opening up the system of government-controlled wholesale markets - so-called mandis - and limiting minimum support prices. They eventually succeeded in having laws withdrawn.

However, as Statista's Katharina Buchholz reports, while guaranteed minimum prices provide security for farmers to at least sell some of their harvest at a profit, few farmers have actually been able to take advantage of the system in the past. This is tied to the fact that the government's ability to buy and redistribute agricultural products is limited.

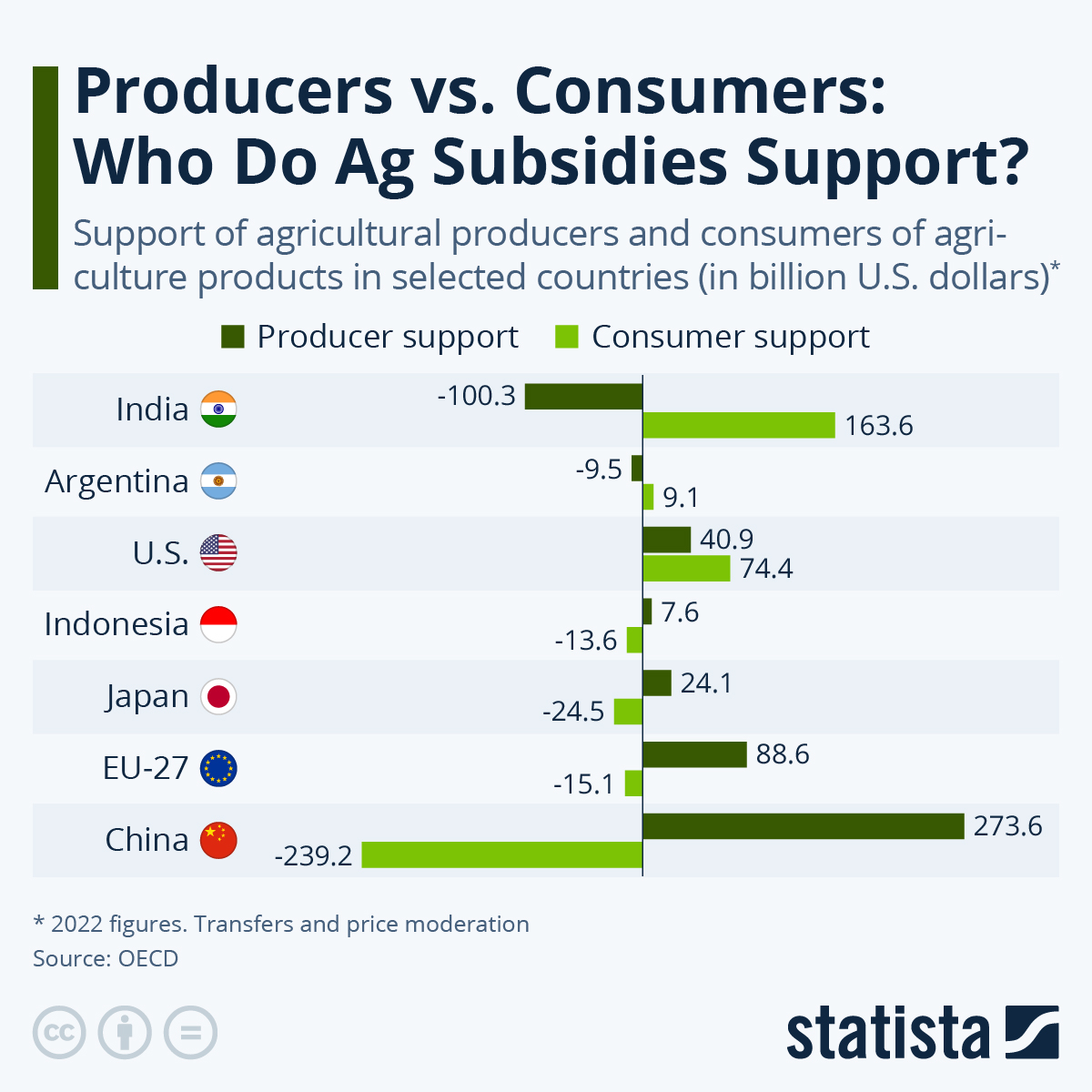

Experts interviewed by Money Control lobbied to help farmers through subsidies other than price moderation, a policy very common around the world in agriculture. In fact, many countries around the world support their farmers with financial help while at the same time asking their consumers and taxpayers to pay more for agricultural products, as seen in data by the OECD.

You will find more infographics at Statista

India, however, is not among these nations. While the country's policy issues do not exactly line up with farmers' demands for change, the grievances of the Indian agricultural sector are plentiful in an international comparison. In its 2022 Agricultural Policy Monitoring report, the OECD notes that Indian "policies that affect farm prices provide implicit support to consumers" and that between 2020 and 2022 "restrictive domestic marketing policies and border measures reduced prices below those on international markets".

This means that while minimum support prices can aid farmers, Indian agricultural policies as a whole disadvantage and implicitly tax them.

The OECD estimated losses to Indian farmers at $163.6 billion in 2022 even after deducting any financial support payments or discounts that producers also receive. Through keeping prices low in the wholesale markets and additionally helping consumers through programs like the Targeted Public Distribution System, which distributes food to poor families, the Indian government is saving consumers more than $100 billion per year.

In Argentina, which has a similar distribution of agriculture support, farmers’ incomes were suppressed by roughly $9.5 billion, while consumers were aided to the tune of $9.1 billion.

Indian farmer protests restarted in early 2024 as talks on the producers’ demands to set more legally binding minimum support prices for agricultural products have broken down.

The borders of city state and capital Delhi have been fortified but farmers from surrounding areas seem determined to push past the barricades this week armed with heavy equipment, supplies and masks to fend off tear gas deployed by police. Ahead of the presidential elections in April and May, farmers once again want to make their grievances heard. Similar protests rocked India previously in 2020 and 2021 as farmers vehemently opposed opening up the system of government-controlled wholesale markets – so-called mandis – and limiting minimum support prices. They eventually succeeded in having laws withdrawn.

However, as Statista’s Katharina Buchholz reports, while guaranteed minimum prices provide security for farmers to at least sell some of their harvest at a profit, few farmers have actually been able to take advantage of the system in the past. This is tied to the fact that the government’s ability to buy and redistribute agricultural products is limited.

Experts interviewed by Money Control lobbied to help farmers through subsidies other than price moderation, a policy very common around the world in agriculture. In fact, many countries around the world support their farmers with financial help while at the same time asking their consumers and taxpayers to pay more for agricultural products, as seen in data by the OECD.

You will find more infographics at Statista

India, however, is not among these nations. While the country’s policy issues do not exactly line up with farmers’ demands for change, the grievances of the Indian agricultural sector are plentiful in an international comparison. In its 2022 Agricultural Policy Monitoring report, the OECD notes that Indian “policies that affect farm prices provide implicit support to consumers” and that between 2020 and 2022 “restrictive domestic marketing policies and border measures reduced prices below those on international markets”.

This means that while minimum support prices can aid farmers, Indian agricultural policies as a whole disadvantage and implicitly tax them.

The OECD estimated losses to Indian farmers at $163.6 billion in 2022 even after deducting any financial support payments or discounts that producers also receive. Through keeping prices low in the wholesale markets and additionally helping consumers through programs like the Targeted Public Distribution System, which distributes food to poor families, the Indian government is saving consumers more than $100 billion per year.

In Argentina, which has a similar distribution of agriculture support, farmers’ incomes were suppressed by roughly $9.5 billion, while consumers were aided to the tune of $9.1 billion.

Loading…