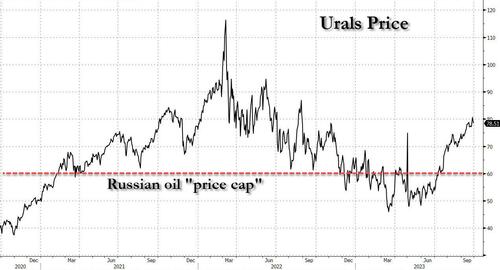

When western nations rolled out a grand plan to throttle Russian oil imports and impose sanctions on Kremlin energy exports, we - and many others - laughed: after all, we have repeatedly seen how toothless western sanctions are when seeking to contain "rogue regime" oil profits, from Iran (which is pretty much selling oil to China at max capacity) to Venezuela and onward. One year later, our laughter has been well justified, because as the FT reports, "Russia has succeeded in avoiding G7 sanctions on most of its oil exports", a shift in trade flows that will boost the Kremlin’s revenues as crude rises towards $100 a barrel, and as Russian Urals prices hit $80, the highest level in over a year.

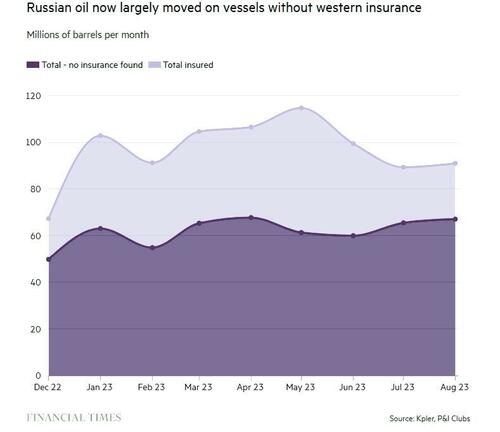

According to the report, almost 75% of all seaborne Russian crude flows traveled without western insurance in August, the only lever used to enforce the G7’s $60-a-barrel oil price cap, according to an analysis of shipping and insurance records by the Financial Times. That is up from about about half this spring, according to data from freight analytics company Kpler and insurance companies. The rise implies that Moscow is becoming more adept at circumventing the cap, allowing it to sell more of its oil at prices closer to international market rates.

More importantly, it means that few if any Russian clients are worried about retaliation by the Biden regime for purchasing Russian oil.

The FT reports that the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) has estimated that the steady increase in crude prices since July, combined with Russia’s success in reducing the discount on its own oil, means that the country’s oil revenues are likely to be at least $15bn higher for 2023 than they would have been; it is also an indication that for all its talk and posturing the West is content with allowing Putin's regime to benefit from surging oil prices as the far more draconian alternative of taking all Russian oil off the market, would have sent global oil prices much higher.

Indeed, as the FT admits, while the EU and US have largely barred imports of Russian oil, the G7 price cap was designed to keep Russian oil flowing into global markets: "The aim was to prevent a squeeze on supplies and an economically and politically damaging jump in prices."

The shift is a double blow for western efforts to restrict Russia’s revenues from oil sales — which make up the biggest part of the Kremlin’s budget — following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Not only is a higher proportion of Russian oil being sold outside the cap, but Moscow’s increasing independence as a seller has coincided with a strong rally in oil prices, which topped $95 a barrel for the first time in 13 months this week.

Worst of all for Western neocons, while Russia’s oil sector is still facing several challenges, including claims of shortages in its domestic refined fuels market and a dip in export volumes overall, the figures still suggest more oil revenues will be flowing into the Kremlin’s war chest.

Ben Hilgenstock, an economist at the KSE, said: “Given these shifts in how Russia ships its oil, it may be very difficult to meaningfully enforce the price cap in future. And that makes it even more regrettable that we did not do more to properly enforce it when we had more leverage.”

Meanwhile, in further weaponization of its commodities (in response to the US weaponization of the US Dollar), Russia this week banned the export of diesel and other fuels, a significant move from one of the biggest global sellers of diesel. The move has raised fears that Russian president Vladimir Putin is trying to disrupt the oil market as he did with natural gas, sparking last year’s energy crisis.

And while the Kremlin is steamrolling western export sanctions, it is Beijing that is allowing Russia to evade import sanctions.

A new study has found that Russia is using Chinese currency for at least a fifth of its imports, illustrating both Moscow’s increasing reliance on Beijing and its efforts to evade western sanctions.

As a reminder, sanctions imposed on Moscow by the EU, US and others as a result of its war against Ukraine have made it increasingly difficult for Russia to get hold of large amounts of western imports. It’s also made it more expensive for it to trade using the dollar, euro or other western currencies, especially after Russia was effectively kicked out of SWIFT and its banks can no longer transact in dollars.

What happened then? Well, by the end of 2022, 20% of Russia’s imports were invoiced in yuan — up from 3% a year previously, according to a research paper published this morning by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the FT reported.

While some of that increase is owing to increased imports from China itself, the use of yuan to settle imports from third countries rose to 5% from just 1% before the war was launched in February 2022.

“Yuan is being used as a vehicle currency,” said Beata Javorcik, the EBRD’s chief economist and one of the paper’s authors. “Russia is now the third-largest clearing centre for offshore yuan transactions.”

Asking trade partners to invoice them in yuan is just one way Moscow is evading sanctions, alongside tactics such as importing products through middleman countries or exporting its oil on tankers that sail without western insurance.

The EBRD paper makes stark just how much Moscow is avoiding western banks when trying to bypass sanctions: when it comes to sanctioned goods and dual-use equipment, which can be used by civilians but also to make weapons, “the increase in [yuan] invoicing was more pronounced,” the paper found. The research also strikes a warning for any western policymakers who might see the data as a sign that their measures are working.

“Rising geopolitical tensions in general, and the use of trade sanctions in particular, may reduce the attractiveness of the use of the US dollar as a vehicle currency in international trade,” they write. “This, in turn, might lead to a greater fragmentation of global payment systems.”

Yet despite all the signs, in a few years there will still be those who are stunned to learn that the dollar is no longer the world's reserve currency.

When western nations rolled out a grand plan to throttle Russian oil imports and impose sanctions on Kremlin energy exports, we – and many others – laughed: after all, we have repeatedly seen how toothless western sanctions are when seeking to contain “rogue regime” oil profits, from Iran (which is pretty much selling oil to China at max capacity) to Venezuela and onward. One year later, our laughter has been well justified, because as the FT reports, “Russia has succeeded in avoiding G7 sanctions on most of its oil exports”, a shift in trade flows that will boost the Kremlin’s revenues as crude rises towards $100 a barrel, and as Russian Urals prices hit $80, the highest level in over a year.

According to the report, almost 75% of all seaborne Russian crude flows traveled without western insurance in August, the only lever used to enforce the G7’s $60-a-barrel oil price cap, according to an analysis of shipping and insurance records by the Financial Times. That is up from about about half this spring, according to data from freight analytics company Kpler and insurance companies. The rise implies that Moscow is becoming more adept at circumventing the cap, allowing it to sell more of its oil at prices closer to international market rates.

More importantly, it means that few if any Russian clients are worried about retaliation by the Biden regime for purchasing Russian oil.

The FT reports that the Kyiv School of Economics (KSE) has estimated that the steady increase in crude prices since July, combined with Russia’s success in reducing the discount on its own oil, means that the country’s oil revenues are likely to be at least $15bn higher for 2023 than they would have been; it is also an indication that for all its talk and posturing the West is content with allowing Putin’s regime to benefit from surging oil prices as the far more draconian alternative of taking all Russian oil off the market, would have sent global oil prices much higher.

Indeed, as the FT admits, while the EU and US have largely barred imports of Russian oil, the G7 price cap was designed to keep Russian oil flowing into global markets: “The aim was to prevent a squeeze on supplies and an economically and politically damaging jump in prices.”

The shift is a double blow for western efforts to restrict Russia’s revenues from oil sales — which make up the biggest part of the Kremlin’s budget — following its full-scale invasion of Ukraine.

Not only is a higher proportion of Russian oil being sold outside the cap, but Moscow’s increasing independence as a seller has coincided with a strong rally in oil prices, which topped $95 a barrel for the first time in 13 months this week.

Worst of all for Western neocons, while Russia’s oil sector is still facing several challenges, including claims of shortages in its domestic refined fuels market and a dip in export volumes overall, the figures still suggest more oil revenues will be flowing into the Kremlin’s war chest.

Ben Hilgenstock, an economist at the KSE, said: “Given these shifts in how Russia ships its oil, it may be very difficult to meaningfully enforce the price cap in future. And that makes it even more regrettable that we did not do more to properly enforce it when we had more leverage.”

Meanwhile, in further weaponization of its commodities (in response to the US weaponization of the US Dollar), Russia this week banned the export of diesel and other fuels, a significant move from one of the biggest global sellers of diesel. The move has raised fears that Russian president Vladimir Putin is trying to disrupt the oil market as he did with natural gas, sparking last year’s energy crisis.

And while the Kremlin is steamrolling western export sanctions, it is Beijing that is allowing Russia to evade import sanctions.

A new study has found that Russia is using Chinese currency for at least a fifth of its imports, illustrating both Moscow’s increasing reliance on Beijing and its efforts to evade western sanctions.

As a reminder, sanctions imposed on Moscow by the EU, US and others as a result of its war against Ukraine have made it increasingly difficult for Russia to get hold of large amounts of western imports. It’s also made it more expensive for it to trade using the dollar, euro or other western currencies, especially after Russia was effectively kicked out of SWIFT and its banks can no longer transact in dollars.

What happened then? Well, by the end of 2022, 20% of Russia’s imports were invoiced in yuan — up from 3% a year previously, according to a research paper published this morning by the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development, the FT reported.

While some of that increase is owing to increased imports from China itself, the use of yuan to settle imports from third countries rose to 5% from just 1% before the war was launched in February 2022.

“Yuan is being used as a vehicle currency,” said Beata Javorcik, the EBRD’s chief economist and one of the paper’s authors. “Russia is now the third-largest clearing centre for offshore yuan transactions.”

Asking trade partners to invoice them in yuan is just one way Moscow is evading sanctions, alongside tactics such as importing products through middleman countries or exporting its oil on tankers that sail without western insurance.

The EBRD paper makes stark just how much Moscow is avoiding western banks when trying to bypass sanctions: when it comes to sanctioned goods and dual-use equipment, which can be used by civilians but also to make weapons, “the increase in [yuan] invoicing was more pronounced,” the paper found. The research also strikes a warning for any western policymakers who might see the data as a sign that their measures are working.

“Rising geopolitical tensions in general, and the use of trade sanctions in particular, may reduce the attractiveness of the use of the US dollar as a vehicle currency in international trade,” they write. “This, in turn, might lead to a greater fragmentation of global payment systems.”

Yet despite all the signs, in a few years there will still be those who are stunned to learn that the dollar is no longer the world’s reserve currency.

Loading…