Cesium-soaked truffles from weapons tests after the Second World War in Central Europe and the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986 have created an unexpected consequence: Radioactive wild boar roaming forests and fields, rendering them unsafe for human consumption.

In a new study published in the American Chemical Society's (ACS) Environmental Science and Technology journal, researchers from the Vienna University of Technology said Europe was covered in radioactive cesium contamination following the Chernobyl power plant accident four decades ago. Most of the radioactivity was cesium-137, but a much longer-lived form, called cesium-135, from nuclear fission was also found. Over the years, cesium-137 declined in most wild animals, but what piqued the interest of researchers was why wild boars' radioactivity remained unchanged.

In a simplified summary, ACS explained in a press release how the researchers were able to determine nuclear explosions from the mid-20th century were responsible for today's radioactive boar in Germany:

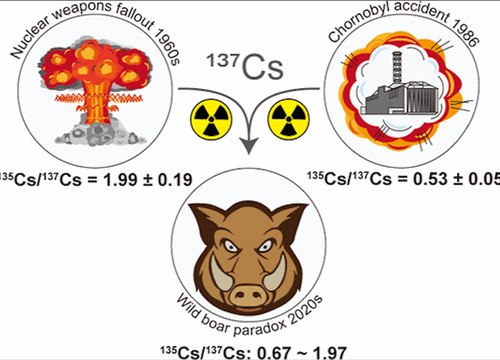

The researchers worked with hunters to collect wild boar meat from across Southern Germany and then measured the samples' cesium-137 levels with a gamma-ray detector. To determine the origin of the radioactivity, the team compared the amount of cesium-135 to cesium-137 with a sophisticated mass spectrometer. Previous studies showed that this ratio clearly indicates sources: A high ratio points to nuclear weapons explosions, whereas a low ratio implicates nuclear reactors.

Here's a summary of the findings:

The team observed that 88% of the 48 meat samples exceeded German regulatory limits for radioactive cesium in food. For the samples with elevated levels, the researchers calculated the ratios of cesium-135 to cesium-137, and found that nuclear weapons testing supplied between 10 and 68% of the contamination. And in some samples, the amount of cesium from weapons alone exceeded regulatory limits.

Researchers believe the nuclear fallout from the nuke tests contaminated the soil soaked up by underground mushrooms. These mushrooms are primarily eaten only by boars, hence why radioactivity levels in these animals were high compared with others.

"This is one of the ultimate case studies showing how legacy soil pollution can haunt generations to come," James Kaste, a geochemist at the College of William & Mary, who wasn't involved in the study, told Science.

Cesium-soaked truffles from weapons tests after the Second World War in Central Europe and the Chernobyl nuclear accident in 1986 have created an unexpected consequence: Radioactive wild boar roaming forests and fields, rendering them unsafe for human consumption.

In a new study published in the American Chemical Society’s (ACS) Environmental Science and Technology journal, researchers from the Vienna University of Technology said Europe was covered in radioactive cesium contamination following the Chernobyl power plant accident four decades ago. Most of the radioactivity was cesium-137, but a much longer-lived form, called cesium-135, from nuclear fission was also found. Over the years, cesium-137 declined in most wild animals, but what piqued the interest of researchers was why wild boars’ radioactivity remained unchanged.

In a simplified summary, ACS explained in a press release how the researchers were able to determine nuclear explosions from the mid-20th century were responsible for today’s radioactive boar in Germany:

The researchers worked with hunters to collect wild boar meat from across Southern Germany and then measured the samples’ cesium-137 levels with a gamma-ray detector. To determine the origin of the radioactivity, the team compared the amount of cesium-135 to cesium-137 with a sophisticated mass spectrometer. Previous studies showed that this ratio clearly indicates sources: A high ratio points to nuclear weapons explosions, whereas a low ratio implicates nuclear reactors.

Here’s a summary of the findings:

The team observed that 88% of the 48 meat samples exceeded German regulatory limits for radioactive cesium in food. For the samples with elevated levels, the researchers calculated the ratios of cesium-135 to cesium-137, and found that nuclear weapons testing supplied between 10 and 68% of the contamination. And in some samples, the amount of cesium from weapons alone exceeded regulatory limits.

Researchers believe the nuclear fallout from the nuke tests contaminated the soil soaked up by underground mushrooms. These mushrooms are primarily eaten only by boars, hence why radioactivity levels in these animals were high compared with others.

“This is one of the ultimate case studies showing how legacy soil pollution can haunt generations to come,” James Kaste, a geochemist at the College of William & Mary, who wasn’t involved in the study, told Science.

Loading…