Evanston, Illinois has been referred to as the new epicenter of the civil rights movement, when in 2019, it became the first city in America to guarantee funding for reparations to black residents. The program has been hailed by other cities looking to implement something similar, but it has brought unintended, unfortunate consequences. In part two of this series, Reparations Nation, the Washington Examiner looks at how the controversial scheme hasn’t always worked for recipients as intended.

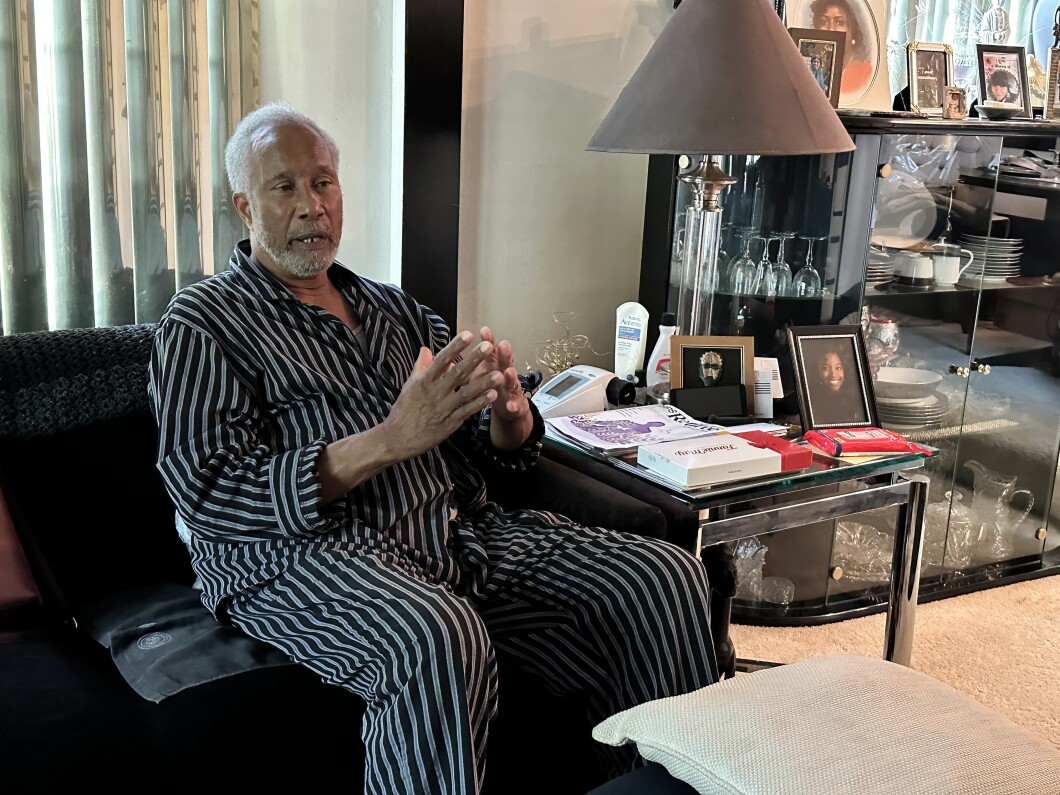

EVANSTON, Illinois — Anthony Swope still remembers the first time he saw his wife, Eleanor. He was coming up the stairs at a new church, and the sun had caught her silhouette.

“I just froze,” he told the Washington Examiner about the woman standing before him. “She saw me staring, and she even tried to hide a little, but we both knew. It was love at first sight.”

Swope was supposed to move to California, where there were more opportunities for young black men, but he couldn’t say goodbye to Eleanor. So he stayed — first at the YMCA, where he rented a room by the week, and then to her house in Evanston, where they would live together for the next 40 years.

Life in the small Illinois city on the outskirts of Chicago took some adjusting and was different from what Swope had experienced growing up in Kentucky.

“We had a black high school, a black junior high school, a black grade school, and we even had bars, taverns, and nightclubs,” he said. “When I moved to Evanston, I was so shocked.”

The inequality was deafening, and the line between the haves and the have-nots was impossible to miss, Swope said, adding that he tried to create a sense of community but was shot down by elders who had written Evanston off as an enclave where racism and unfairness fostered. Even today, the median white household income in Evanston is $108,000 compared to $55,000 in black households.

An attempt to level the playing field took place five years ago when a first-of-its-kind plan was introduced that would give black residents in Evanston, affected by Jim Crow-era laws, $25,000 to help with a down payment on a house, mortgage, or home repairs. Unlike other reparation programs that are based around the slave trade, Evanston’s addressed unfair housing policies. It’s also different because people affected by Jim Crow and redlining, a discriminatory practice that involves the systematic denial of services such as mortgages and loans based on race, are still alive and can directly benefit from the program.

Evanston has become a prototype of sorts, and several other cities and states across the United States and beyond have been watching to see how it runs its program and navigates problems that pop up.

Swope, who had lived in Evanston long enough to call it home, convinced his wife, a cosmetologist for 61 years who had opened LaPetite House of Beauty on the first floor of their building, to apply for the reparations program. When she qualified, the couple began making plans on what to do with the funds. That came to an abrupt stop in November when Eleanor had a heart attack and died.

Swope’s world would never be the same, and he was told that the building improvements he and his wife had dreamt of would not come to fruition because there had been nothing in writing that would have allowed the funds to be transferred to him or Eleanor’s children.

So far, seven Evanstonians who were eligible to receive reparations have died waiting for their money.

The city has only spent $400,000 of the $10 million promised in 2019. Not only has the payout been slow, but there have been other problems that have plagued the program and led to unintended consequences, including identity theft and online predators targeting the elderly.

Ramona Burton, one of the first 16 recipients chosen for the city’s historic program, told the Washington Examiner her identity was stolen after her name was publicly released. Her minister told her to put out statements on social media that the money she received was not in cash form and therefore could not be handed out to people who asked.

Burton, whose husband died more than 30 years ago, spent her money on renovations which included new windows, a new roof, construction of a partial fence, and chimney repairs. The outspoken Evanstonian sent a thank you note to the reparations committee after being picked via a lottery system. She said she’s proud to represent the inaugural class but understands the pushback from some in the community who say the money is not enough to erase decades of hardship.

“I think it’s a start, but I do think it’s low compared to what we went through,” she said. “But it’s better than nothing. It’s a start.”

Being part of the first group has unfortunately made Burton the target of online scammers, and she has largely had to navigate the cyber landmines alone.

Robin Rue Simmons, a former councilwoman and the architect of the reparations program, told the Washington Examiner that she, too, has been targeted but stated there simply aren’t enough resources available to shield awardees from nefarious actors.

In March, the program faced another complication when two of its first round of recipients, Kenneth Wideman and his sister Sheila Wideman, said they were happy with their rental apartments and did not want to become first-time homeowners. That created a problem because the city’s program had explicitly prevented direct payouts. And even though $25,000 was a hefty sum, a single-family house in one of the wealthiest stretches of land in America could easily exceed $500,000, excluding upkeep, which made ownership a dream for most.

“Taking care of a house would be really a burden on me and my sister,” 77-year-old Kenneth Wideman said. “That’s why we got apartments.”

With the world watching, the city’s seven-member reparations committee decided to open up a fourth option, one that the program’s critics had been waiting for: a direct cash payout that could be used for rent or other housing expenses. Unlike the previous options, the money would be taxable and could bump recipients into another tax bracket, putting their eligibility for other government assistance programs, like SNAP and health insurance, on the line.

The committee also fast-tracked plans to create a new program that would pay an undetermined amount of money with no strings attached, something Burton predicted would be disastrous.

“If you just hand out money, who’s to say what they are going to use it for?” she said. “There has to be a check and balance. I think it’s a big mistake.”

Councilwoman Krissie Harris, a fifth-generation Evanstonian who represents the 2nd Ward, had a more optimistic take. In an interview with the Washington Examiner, Harris said growing pains were to be expected with any new program but that they would be addressed accordingly.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“I think we are the catalyst for change,” Harris, who is on the reparations committee, said. “I know everybody is watching Evanston and how we do this. We’re trying our very best to get it right each and every time, look at it, and assess it. Not everyone is going to be happy and we know that and we just have to do the best we can by our mission.”

Catch part three of this series on the reparations program’s architect battling Northwestern University tomorrow.