By Chris Bennett of AgWeb

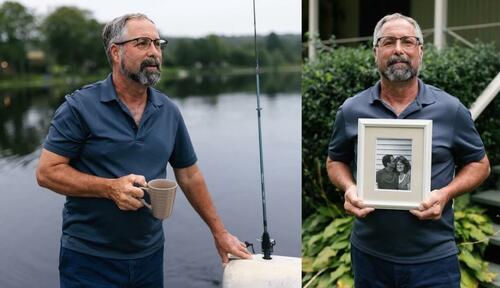

Twice accused, twice vindicated, and twice insistent on the sanctity of the Fourth Amendment. After Tim Thomas’ property was entered and searched on multiple occasions by state officials without warrant or consent in 2023, he filed a federal lawsuit challenging the power of water conservation officers to access private property.

“All other law enforcement officials at every level must have a warrant to do what a water conservation officer did around my house,” says 62-year-old Thomas. “I’m suing to get a law changed because this should never happen to anyone else. I want people to know what’s gone on at my property, and to my family, and how our rights were trampled.”

Wherever and Whenever?

On May 13, 2023, Thomas’ wife, Stephanie, was alone inside the couple’s single-story lakeside cottage at the end of a gravel road on the shoreline of 80-acre Butler Lake in Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna County. Their property encompassed less than 1 acre of ground, including a dock and 300’ of shoreline.

Together, the couple owned Thomas’ Chimneys & Stoves in nearby Kingsley. “We had the business for 42 years,” Thomas says. “I’ve always respected the law and done my best to serve the community as a deacon and citizen. People are blown away when they hear what happened on our quiet property.”

(Photo by IJ)

Diagnosed with breast cancer in 2022, Stephanie was non-ambulatory during a period of recovery following a round of stage 4 treatment. According to the complaint filed in Thomas’ subsequent lawsuit via representation by Institute for Justice (IJ), Stephanie heard someone loudly knocking on the front door of the cottage. The individual then went around the side of the house, past no-trespassing signs, entered the back yard, walked onto the back porch, and began “pounding” on the back door. Stephanie did not know the individual at her doorstep was Water Conservation Officer (WCO) Ty Moon of the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC).

Alarmed, Stephanie used a walker to retreat to a bedroom. Per the complaint: “While pounding on the front and back doors of the cabin, WCO Moon yelled, ‘I know you’re in there,’ and ‘I’m going to call the police.’”

(Citing open litigation, PFBC declined comment related to Tim Thomas’ lawsuit.)

“She peeked through the drapes and saw a man she didn’t know in dark clothes yelling, and she managed to get into our room,” Thomas describes.

While Stephanie hid, Moon peered in the windows and then moved about the property, according to Thomas, taking pictures of the home, motor vehicle, and pontoon boat.

The ball began rolling on a steady chain of glaring constitutional violations, contends IJ attorney Kirby West: “The government cannot go wherever and whenever it wants—that’s the very reason for the Fourth Amendment in the first place. We see a lot of cases where government goes overboard, but this statute is the plainest example I’ve seen that contradicts the Fourth Amendment on its face.”

Search, Seizure, Citation

On Mother’s Day, May 14, a day after WCO Moon entered their property, the Thomas duo stopped roadside, roughly 1 mile from home. “We were on our way back from church and I pulled over to pick Stephanie her favorite flowers—lilacs,” Thomas recalls.

“As I was picking, a white truck pulled in front of us, and a tall man I didn’t know came angrily towards me, shouting that he’d seen me fishing the day before and claiming I had refused to talk to him. He got up close and started yelling in my face that he’d ‘get to the bottom of things,’ but I had done nothing wrong and had no idea what he was talking about. Other than the knocks on the door the day prior, this was the first time either Stephanie or myself had met or even heard of Ty Moon.”

Four days later, a PFBC citation arrived in the mail, accusing Thomas of fishing without a license and fleeing on May 13: Def. did willfully refuse to bring boat to a stop, flee after given an audible signal. Thereafter, attempted to elude a WCO.

“We were accused of trying to get away from Ty Moon while fishing. It was preposterous,” Thomas says. “My wife with stage 4 cancer fleeing from the law on the water? Supposedly Moon was onshore, and we fled by boat. We never saw him, don’t know where he was standing, and certainly didn’t run away. Bottom line, the charges were bogus, but that’s why he came knocking later at our house.”

Since age 12, Thomas had obtained Pennsylvania hunting and fishing licenses. He had never been ticketed for a wildlife violation in his life—until May 2023.

In response to the citation and a fine nearing $462, Thomas telephoned Moon’s superiors and sent a letter of complaint to Captain Tom Edwards, manager of PFBC’s northwest region. Edwards personally called Thomas; all charges were dropped.

“I considered it over,” Thomas says. “My wife didn’t. She told me, ‘Whatever is going on, I don’t think he (Moon) is through with you.’”

Several months later, Moon was back on Thomas’ property for another search, seizure, and citation.

Vendetta

At roughly 9 a.m., on Aug. 12, 2023, Thomas piloted his pontoon boat home after fishing on Lake Butler.

As Thomas pulled to his dock, WCO Moon approached Thomas’ property on foot, walked along the driveway to the side of the cabin, entered the back yard via a gap between bushes and structure, and passed by a bathroom window—ignoring a total of four no-trespassing signs, according to the complaint.

Arriving at the dock, Moon accused Thomas of exceeding regulation by fishing with eight rods/lines. “Untrue charges,” Thomas says. “But in that moment, Ty Moon’s charges weren’t my main concern. I was worried about Stephanie.”

In accessing the back yard, Moon had walked by a window where Thomas’ wife was bathing. “The house was our sanctuary after Stephanie was diagnosed, and because of the way we set up the bushes and landscaping, the bathroom provided her with a place to soak and look out at the scenery in total privacy with the curtains open, just inside the window in a clawfoot tub—the same window where a state water officer had just come within an arm’s length.”

“I wanted him off our property and away from the window where my wife—a cancer patient—was exposed.”

Thomas informed Moon he was trespassing, and insisted on continuing the conversation on the public road. Once the men were out of the back yard and on the edge of the driveway, Moon asked for Thomas’ fishing license and boat registration. Thomas provided the license. However, the registration was inside the boat.

Thomas offered to get the registration. Moon declined, announcing his intention to reenter the back yard to obtain the paperwork and perform a safety inspection on the boat. Despite Thomas’ protests, Moon walked back to the dock and boat. Moon returned—and then announced he need to return to the dock a third time to confiscate Thomas’ fishing rods.

“Three times,” Thomas says, “with me telling him no, over and over. Three violations of our private space while my wife was dying. Officer Moon knew my wife was a cancer patient because I told him. It’s hard to describe the frustration and needless abuse of power.”

After confiscating Thomas’ rods, Moon ended the encounter with a $354 citation for fishing with eight rods/lines: Def. did fish with more than the maximum amount of devices while in Commonwealth waters.

Thomas says the charges are false. “Officer Moon said he’d been watching me with binoculars since around 8 a.m. from a boat ramp several hundred yards away and could see eight lines in the water. No way, period. I had three lines in the water and no more. And who believes he just happened to be on the shore, just passing by the area, on tiny Butler Lake? I suspect he had a vendetta against me; that’s my opinion.”

29 Hours

In November 2023, several months after the second citation, Thomas appeared in Magisterial court. The PFBC citation stated Thomas had eight lines in the water—therefore Thomas owed $354. Case closed.

“The evidence didn’t matter,” Thomas says. “I was supposed to accept the fine and shut up. No. I place the highest value on individual liberty and there are tremendous repercussion effects when the government abuses power.”

Beyond his main vocation as a chimney business owner, Thomas often drove for Lyft and Uber. After the criminal citation was filed, he automatically lost both driving jobs—banned by both companies due to the legal violation.

Thomas appealed the PFBC citation to a Commonwealth court. On June 5, 2024, Thomas’ case was heard. “The judge actually was interested to know all the evidence, and when he heard what Moon claimed to have seen and what Moon did, he knew things weren’t adding up. We won—for the second time.”

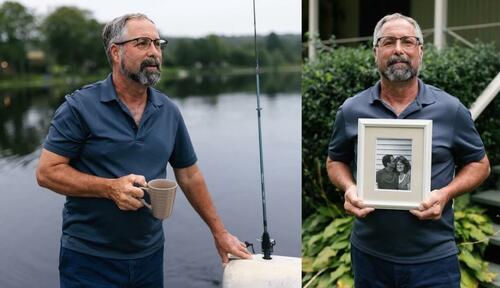

However, Thomas’ court victory was bookended by the heaviest blow of his life: 29 hours after the judge’s decision, Stephanie lost her cancer battle and passed away.

“In memory of my wife, and to ensure no other families are dealt with by the state like this, I’m making a stand,” Thomas says. “In open court, out loud, Officer Moon said he wasn’t bound by no-trespassing signs, and said he had a mandate to go anywhere. He is wrong because private property is sacred. The Fourth Amendment and its protection from search and seizure is the only thing standing between us and tyranny.”

No Monetary Gain

According to 12 words of Pennsylvania state code, PFBC officials have authority to “enter upon any land or water in the performance of their duties.” The statue provides wide latitude for PFBC to enter onto any property without consent, probable cause, or warrant—with no limits on duration, frequency, or scope.

Represented by Institute for Justice (IJ), Thomas sued PFBC in September 2024.

The PFBC statute provides water conservation officers with more latitude than all other types of law enforcement, says IJ attorney West. Even the wide-ranging Open Fields doctrine (currently under legal challenge in multiple states) denies government representatives the power to enter curtilage—the greater yard area surrounding a home. Yet, PFBC asserts power beyond Open Fields.

“The Commission believes these types of invasions, such as happened at Tim Thomas’, are within their law enforcement powers,” West adds, “but when people first hear about Tim’s case, it doesn’t make sense to them because they know it’s an obvious violation of the Fourth Amendment.”

Thomas and Institute for Justice await an answer from PFBC to the initial lawsuit filing.

“There is no monetary gain for me to fight this, I only want this statute declared unconstitutional, so the next landowner or homeowner is protected,” Thomas concludes. “Our framers would roll in their graves to see this case, and I’m willing to invest whatever time it takes so nobody else has to go through the loss of basic constitutional rights.”

By Chris Bennett of AgWeb

Twice accused, twice vindicated, and twice insistent on the sanctity of the Fourth Amendment. After Tim Thomas’ property was entered and searched on multiple occasions by state officials without warrant or consent in 2023, he filed a federal lawsuit challenging the power of water conservation officers to access private property.

“All other law enforcement officials at every level must have a warrant to do what a water conservation officer did around my house,” says 62-year-old Thomas. “I’m suing to get a law changed because this should never happen to anyone else. I want people to know what’s gone on at my property, and to my family, and how our rights were trampled.”

Wherever and Whenever?

On May 13, 2023, Thomas’ wife, Stephanie, was alone inside the couple’s single-story lakeside cottage at the end of a gravel road on the shoreline of 80-acre Butler Lake in Pennsylvania’s Susquehanna County. Their property encompassed less than 1 acre of ground, including a dock and 300’ of shoreline.

Together, the couple owned Thomas’ Chimneys & Stoves in nearby Kingsley. “We had the business for 42 years,” Thomas says. “I’ve always respected the law and done my best to serve the community as a deacon and citizen. People are blown away when they hear what happened on our quiet property.”

(Photo by IJ)

Diagnosed with breast cancer in 2022, Stephanie was non-ambulatory during a period of recovery following a round of stage 4 treatment. According to the complaint filed in Thomas’ subsequent lawsuit via representation by Institute for Justice (IJ), Stephanie heard someone loudly knocking on the front door of the cottage. The individual then went around the side of the house, past no-trespassing signs, entered the back yard, walked onto the back porch, and began “pounding” on the back door. Stephanie did not know the individual at her doorstep was Water Conservation Officer (WCO) Ty Moon of the Pennsylvania Fish and Boat Commission (PFBC).

Alarmed, Stephanie used a walker to retreat to a bedroom. Per the complaint: “While pounding on the front and back doors of the cabin, WCO Moon yelled, ‘I know you’re in there,’ and ‘I’m going to call the police.’”

(Citing open litigation, PFBC declined comment related to Tim Thomas’ lawsuit.)

“She peeked through the drapes and saw a man she didn’t know in dark clothes yelling, and she managed to get into our room,” Thomas describes.

While Stephanie hid, Moon peered in the windows and then moved about the property, according to Thomas, taking pictures of the home, motor vehicle, and pontoon boat.

The ball began rolling on a steady chain of glaring constitutional violations, contends IJ attorney Kirby West: “The government cannot go wherever and whenever it wants—that’s the very reason for the Fourth Amendment in the first place. We see a lot of cases where government goes overboard, but this statute is the plainest example I’ve seen that contradicts the Fourth Amendment on its face.”

Search, Seizure, Citation

On Mother’s Day, May 14, a day after WCO Moon entered their property, the Thomas duo stopped roadside, roughly 1 mile from home. “We were on our way back from church and I pulled over to pick Stephanie her favorite flowers—lilacs,” Thomas recalls.

“As I was picking, a white truck pulled in front of us, and a tall man I didn’t know came angrily towards me, shouting that he’d seen me fishing the day before and claiming I had refused to talk to him. He got up close and started yelling in my face that he’d ‘get to the bottom of things,’ but I had done nothing wrong and had no idea what he was talking about. Other than the knocks on the door the day prior, this was the first time either Stephanie or myself had met or even heard of Ty Moon.”

Four days later, a PFBC citation arrived in the mail, accusing Thomas of fishing without a license and fleeing on May 13: Def. did willfully refuse to bring boat to a stop, flee after given an audible signal. Thereafter, attempted to elude a WCO.

“We were accused of trying to get away from Ty Moon while fishing. It was preposterous,” Thomas says. “My wife with stage 4 cancer fleeing from the law on the water? Supposedly Moon was onshore, and we fled by boat. We never saw him, don’t know where he was standing, and certainly didn’t run away. Bottom line, the charges were bogus, but that’s why he came knocking later at our house.”

Since age 12, Thomas had obtained Pennsylvania hunting and fishing licenses. He had never been ticketed for a wildlife violation in his life—until May 2023.

In response to the citation and a fine nearing $462, Thomas telephoned Moon’s superiors and sent a letter of complaint to Captain Tom Edwards, manager of PFBC’s northwest region. Edwards personally called Thomas; all charges were dropped.

“I considered it over,” Thomas says. “My wife didn’t. She told me, ‘Whatever is going on, I don’t think he (Moon) is through with you.’”

Several months later, Moon was back on Thomas’ property for another search, seizure, and citation.

Vendetta?

At roughly 9 a.m., on Aug. 12, 2023, Thomas piloted his pontoon boat home after fishing on Lake Butler.

As Thomas pulled to his dock, WCO Moon approached Thomas’ property on foot, walked along the driveway to the side of the cabin, entered the back yard via a gap between bushes and structure, and passed by a bathroom window—ignoring a total of four no-trespassing signs, according to the complaint.

Arriving at the dock, Moon accused Thomas of exceeding regulation by fishing with eight rods/lines. “Untrue charges,” Thomas says. “But in that moment, Ty Moon’s charges weren’t my main concern. I was worried about Stephanie.”

In accessing the back yard, Moon had walked by a window where Thomas’ wife was bathing. “The house was our sanctuary after Stephanie was diagnosed, and because of the way we set up the bushes and landscaping, the bathroom provided her with a place to soak and look out at the scenery in total privacy with the curtains open, just inside the window in a clawfoot tub—the same window where a state water officer had just come within an arm’s length.”

“I wanted him off our property and away from the window where my wife—a cancer patient—was exposed.”

Thomas informed Moon he was trespassing, and insisted on continuing the conversation on the public road. Once the men were out of the back yard and on the edge of the driveway, Moon asked for Thomas’ fishing license and boat registration. Thomas provided the license. However, the registration was inside the boat.

Thomas offered to get the registration. Moon declined, announcing his intention to reenter the back yard to obtain the paperwork and perform a safety inspection on the boat. Despite Thomas’ protests, Moon walked back to the dock and boat. Moon returned—and then announced he need to return to the dock a third time to confiscate Thomas’ fishing rods.

“Three times,” Thomas says, “with me telling him no, over and over. Three violations of our private space while my wife was dying. Officer Moon knew my wife was a cancer patient because I told him. It’s hard to describe the frustration and needless abuse of power.”

After confiscating Thomas’ rods, Moon ended the encounter with a $354 citation for fishing with eight rods/lines: Def. did fish with more than the maximum amount of devices while in Commonwealth waters.

Thomas says the charges are false. “Officer Moon said he’d been watching me with binoculars since around 8 a.m. from a boat ramp several hundred yards away and could see eight lines in the water. No way, period. I had three lines in the water and no more. And who believes he just happened to be on the shore, just passing by the area, on tiny Butler Lake? I suspect he had a vendetta against me; that’s my opinion.”

29 Hours

In November 2023, several months after the second citation, Thomas appeared in Magisterial court. The PFBC citation stated Thomas had eight lines in the water—therefore Thomas owed $354. Case closed.

“The evidence didn’t matter,” Thomas says. “I was supposed to accept the fine and shut up. No. I place the highest value on individual liberty and there are tremendous repercussion effects when the government abuses power.”

Beyond his main vocation as a chimney business owner, Thomas often drove for Lyft and Uber. After the criminal citation was filed, he automatically lost both driving jobs—banned by both companies due to the legal violation.

Thomas appealed the PFBC citation to a Commonwealth court. On June 5, 2024, Thomas’ case was heard. “The judge actually was interested to know all the evidence, and when he heard what Moon claimed to have seen and what Moon did, he knew things weren’t adding up. We won—for the second time.”

However, Thomas’ court victory was bookended by the heaviest blow of his life: 29 hours after the judge’s decision, Stephanie lost her cancer battle and passed away.

“In memory of my wife, and to ensure no other families are dealt with by the state like this, I’m making a stand,” Thomas says. “In open court, out loud, Officer Moon said he wasn’t bound by no-trespassing signs, and said he had a mandate to go anywhere. He is wrong because private property is sacred. The Fourth Amendment and its protection from search and seizure is the only thing standing between us and tyranny.”

No Monetary Gain

According to 12 words of Pennsylvania state code, PFBC officials have authority to “enter upon any land or water in the performance of their duties.” The statue provides wide latitude for PFBC to enter onto any property without consent, probable cause, or warrant—with no limits on duration, frequency, or scope.

Represented by Institute for Justice (IJ), Thomas sued PFBC in September 2024.

The PFBC statute provides water conservation officers with more latitude than all other types of law enforcement, says IJ attorney West. Even the wide-ranging Open Fields doctrine (currently under legal challenge in multiple states) denies government representatives the power to enter curtilage—the greater yard area surrounding a home. Yet, PFBC asserts power beyond Open Fields.

“The Commission believes these types of invasions, such as happened at Tim Thomas’, are within their law enforcement powers,” West adds, “but when people first hear about Tim’s case, it doesn’t make sense to them because they know it’s an obvious violation of the Fourth Amendment.”

Thomas and Institute for Justice await an answer from PFBC to the initial lawsuit filing.

“There is no monetary gain for me to fight this, I only want this statute declared unconstitutional, so the next landowner or homeowner is protected,” Thomas concludes. “Our framers would roll in their graves to see this case, and I’m willing to invest whatever time it takes so nobody else has to go through the loss of basic constitutional rights.”

Loading…