By John Kemp, senior market analyst at Reuters

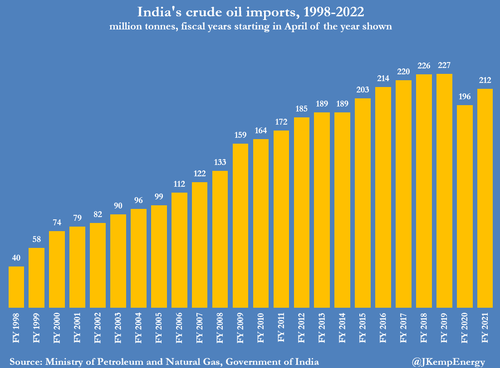

India would be one of the countries most exposed if Russia refuses to sell crude oil at the capped price under proposed sanctions to be imposed by the United States and the European Union. In 2021, India was the world’s third-largest crude importer (214 million tonnes) after China (526 million tonnes) and the United States (305 million tonnes) (“Statistical review of world energy”, BP, 2022).

India and China rely on imports by tanker from the Middle East, Russia and other regions, in contrast to the United States, which receives most of its imports by pipeline from neighbouring Canada.

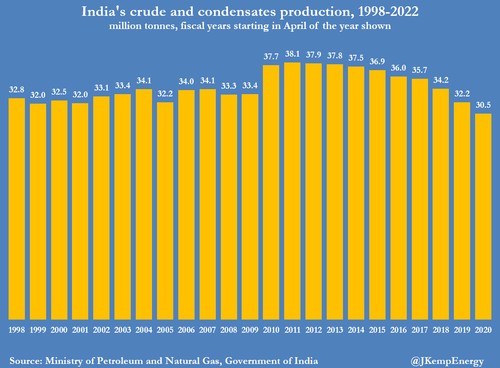

India’s domestic crude and condensate production has been stuck at 30-40 million tonnes per year for the last two decades, data from India’s Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas shows.

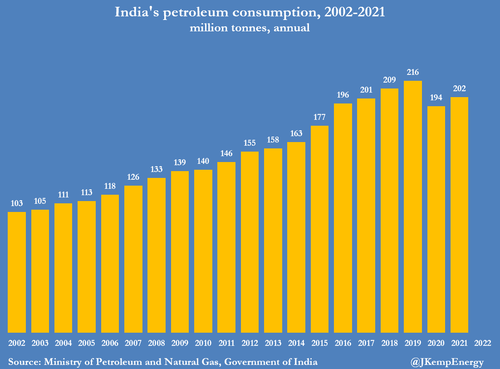

By contrast, domestic petroleum consumption has doubled to 202 million tonnes in 2021 from 103 million tonnes in 2002 (“Snapshot of India’s oil and gas data”, Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell, Nov. 10).

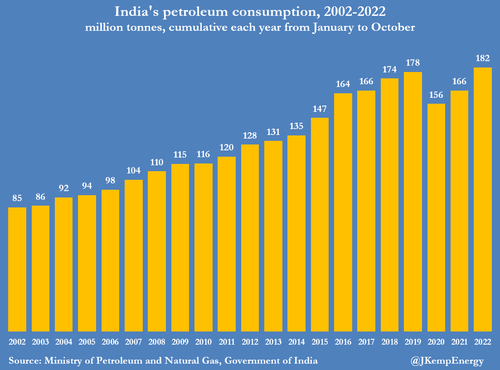

In the first ten months of 2022, India consumed a seasonal record 182 million tonnes, surpassing the previous peak of 178 million in 2019, before the pandemic.

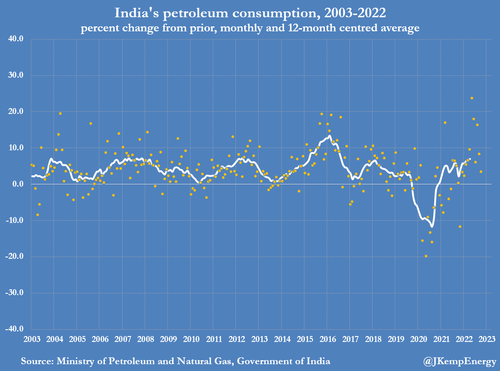

As a lower-middle income country experiencing rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, India’s consumption is growing fast but its consumers are very sensitive to both price changes and the economic cycle.

Consumption has been growing by around 7% per year in the last 12 months, though there were signs of a possible slowdown to around half that rate in October.

Voracious Oil Intake

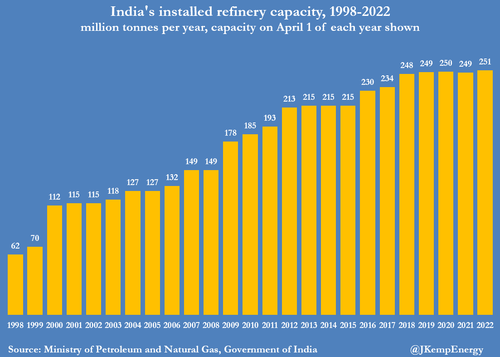

India’s refinery crude processing capacity increased to 251 million tonnes per year in 2021 from 115 million tonnes per year in 2002, and the country has emerged as a major exporter of refined products.

In 2022, India has become a big buyer of Russia’s crude following that country’s invasion of Ukraine and sanctions imposed on its exports in response by the United States, European Union and their allies.

India and China have absorbed additional crude and products imports from Russia, allowing the United States and the European Union to take more crude and fuels from non-sanctioned sources.

Because of its import dependence and price-sensitive consumers, India would be extremely vulnerable should Russia retaliate by refusing to sell crude and fuels at the capped price.

The resulting shortfall in physical crude supplies and surge in prices for both crude and fuels would hit refiners and domestic consumers hard.

Selling the Price Cap

U.S. and EU policymakers have said repeatedly they will set the cap at a level to ensure Russia continues exporting and any halt or reduction to exports would be irrational.

In remarks on Nov. 11 on a a visit to New Delhi, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said the price cap would work in India’s interest by giving it extra leverage to purchase Russian crude at deep discounts.

Russian oil “is going to be selling at bargain prices and we’re happy to have India get that bargain”, Yellen told reporters (“India can buy as much Russian oil as it wants, outside price cap, Yellen says”, Reuters, Nov.11).

Yellen has become the chief advocate for the price cap concept as the Biden administration attempts to sell the idea to sceptical oil buyers and governments in Asia.

India is also an increasingly important diplomatic partner as the United States develops an “Indo-Pacific strategy” to counter China, so the U.S. administration has been anxious to allay fears about the price cap’s impact.

In recent months, the U.S. administration has walked back plans for an ambitious and strictly enforced price cap given concerns about the impact on prices, inflation and the economy at home and in importers like India.

Remarks in the last few weeks have suggested the administration will declare the cap a success if there is any reduction in oil prices received by Russia, whether deals are done under the cap or not.

Further SPR Releases

In contrast to the United States and China, India has limited strategic oil reserves to protect itself from any interruption of imports.

Ultimately, if there is any disruption to Russia’s petroleum exports, the United States will have to ensure India’s refineries remain supplied by releasing more barrels from its own Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR).

Even after recent drawdowns, the SPR contains 396 million barrels of crude, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, equivalent to roughly 50-55 million tonnes, at standard conversion rates.

The reserve is a fixed stock so it cannot replace the flow of Russia petroleum exports indefinitely, and the crude left in the reserve is not a particularly good match for Russia’s export grades.

But further SPR releases could buy policymakers and India’s refiners time and are likely in the event Russia retaliates against the price cap.

By John Kemp, senior market analyst at Reuters

India would be one of the countries most exposed if Russia refuses to sell crude oil at the capped price under proposed sanctions to be imposed by the United States and the European Union. In 2021, India was the world’s third-largest crude importer (214 million tonnes) after China (526 million tonnes) and the United States (305 million tonnes) (“Statistical review of world energy”, BP, 2022).

India and China rely on imports by tanker from the Middle East, Russia and other regions, in contrast to the United States, which receives most of its imports by pipeline from neighbouring Canada.

India’s domestic crude and condensate production has been stuck at 30-40 million tonnes per year for the last two decades, data from India’s Ministry of Petroleum and Natural Gas shows.

By contrast, domestic petroleum consumption has doubled to 202 million tonnes in 2021 from 103 million tonnes in 2002 (“Snapshot of India’s oil and gas data”, Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell, Nov. 10).

In the first ten months of 2022, India consumed a seasonal record 182 million tonnes, surpassing the previous peak of 178 million in 2019, before the pandemic.

As a lower-middle income country experiencing rapid industrialisation and urbanisation, India’s consumption is growing fast but its consumers are very sensitive to both price changes and the economic cycle.

Consumption has been growing by around 7% per year in the last 12 months, though there were signs of a possible slowdown to around half that rate in October.

Voracious Oil Intake

India’s refinery crude processing capacity increased to 251 million tonnes per year in 2021 from 115 million tonnes per year in 2002, and the country has emerged as a major exporter of refined products.

In 2022, India has become a big buyer of Russia’s crude following that country’s invasion of Ukraine and sanctions imposed on its exports in response by the United States, European Union and their allies.

India and China have absorbed additional crude and products imports from Russia, allowing the United States and the European Union to take more crude and fuels from non-sanctioned sources.

Because of its import dependence and price-sensitive consumers, India would be extremely vulnerable should Russia retaliate by refusing to sell crude and fuels at the capped price.

The resulting shortfall in physical crude supplies and surge in prices for both crude and fuels would hit refiners and domestic consumers hard.

Selling the Price Cap

U.S. and EU policymakers have said repeatedly they will set the cap at a level to ensure Russia continues exporting and any halt or reduction to exports would be irrational.

In remarks on Nov. 11 on a a visit to New Delhi, U.S. Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen said the price cap would work in India’s interest by giving it extra leverage to purchase Russian crude at deep discounts.

Russian oil “is going to be selling at bargain prices and we’re happy to have India get that bargain”, Yellen told reporters (“India can buy as much Russian oil as it wants, outside price cap, Yellen says”, Reuters, Nov.11).

Yellen has become the chief advocate for the price cap concept as the Biden administration attempts to sell the idea to sceptical oil buyers and governments in Asia.

India is also an increasingly important diplomatic partner as the United States develops an “Indo-Pacific strategy” to counter China, so the U.S. administration has been anxious to allay fears about the price cap’s impact.

In recent months, the U.S. administration has walked back plans for an ambitious and strictly enforced price cap given concerns about the impact on prices, inflation and the economy at home and in importers like India.

Remarks in the last few weeks have suggested the administration will declare the cap a success if there is any reduction in oil prices received by Russia, whether deals are done under the cap or not.

Further SPR Releases

In contrast to the United States and China, India has limited strategic oil reserves to protect itself from any interruption of imports.

Ultimately, if there is any disruption to Russia’s petroleum exports, the United States will have to ensure India’s refineries remain supplied by releasing more barrels from its own Strategic Petroleum Reserve (SPR).

Even after recent drawdowns, the SPR contains 396 million barrels of crude, according to the U.S. Energy Information Administration, equivalent to roughly 50-55 million tonnes, at standard conversion rates.

The reserve is a fixed stock so it cannot replace the flow of Russia petroleum exports indefinitely, and the crude left in the reserve is not a particularly good match for Russia’s export grades.

But further SPR releases could buy policymakers and India’s refiners time and are likely in the event Russia retaliates against the price cap.