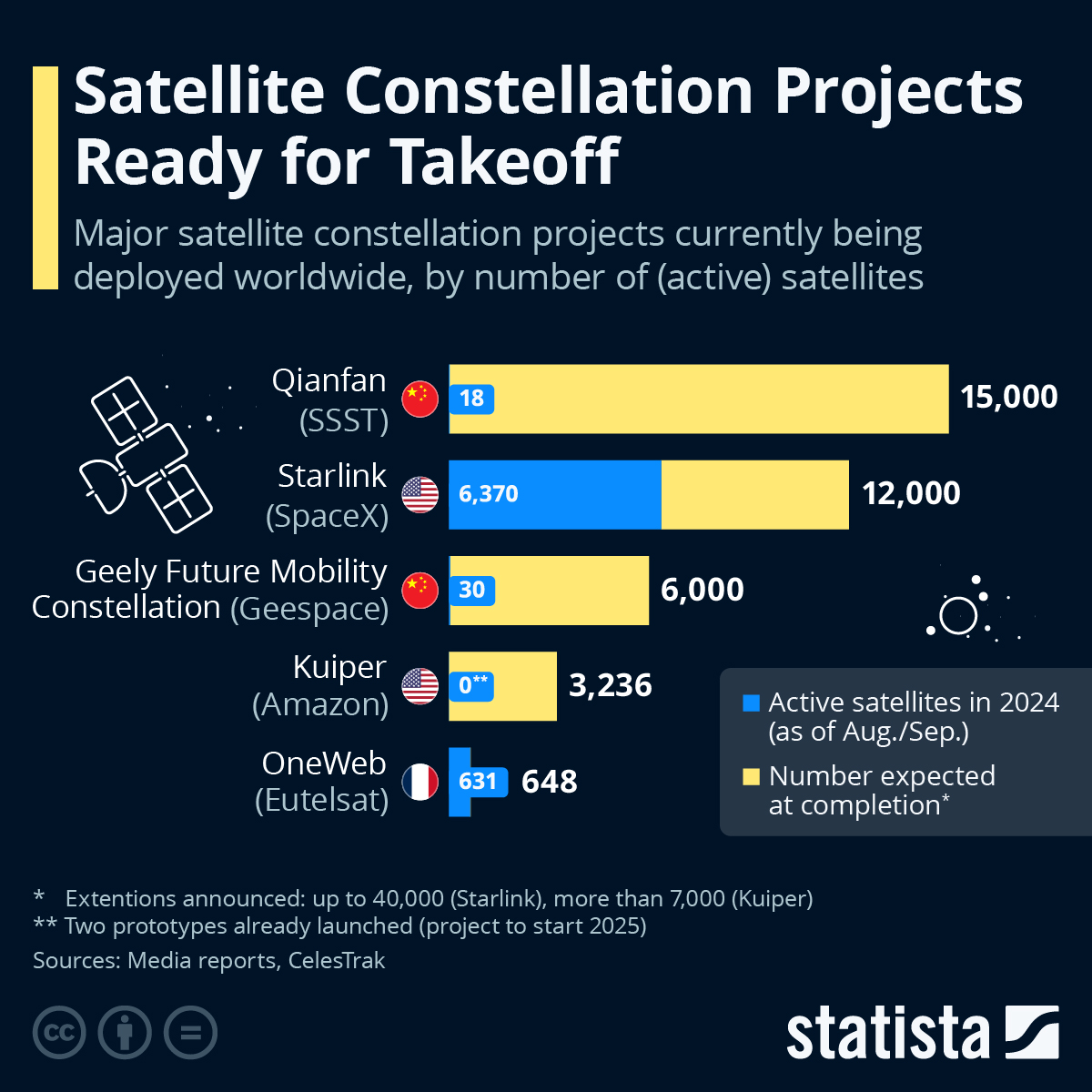

International competition is intensifying for the deployment of satellite constellations into orbit, notes Statista's Katharina Buchholz.

Satellite constellations - the most well-known being SpaceX's Starlink - are designed to provide high-speed global Internet access.

Starlink, launched in 2019, had more than 6,300 satellites in service at the beginning of September, out of 12,000 eventually scheduled to be deployed (or even 40,000 according to an announcement of a possible extension of the project).

Amazon meanwhile plans to put more than 3,200 satellites into orbit as part of its rival Kuiper project.

Following the successful launch of two prototypes last year, the American multinational plans to deploy its first commercial satellites for the project in 2025.

You will find more infographics at Statista

Elsewhere in the world, China is also embarking on large-scale satellite Internet infrastructure projects.

At the beginning of August, the state-owned Shanghai Spacecom Satellite Technology (SSST) launched the first 18 satellites of its Qianfan constellation, which could include more than 15,000 satellites by 2030.

Geespace, a subsidiary of the Chinese car manufacturer Geely, announced that its project had 30 satellites in orbit at the beginning of September, out of the nearly 6,000 planned.

In Europe, French satellite operator Eutelsat entered the fixed and mobile broadband market at the end of 2019. With the recent acquisition of the British low-orbit constellation OneWeb, which will have more than 600 active telecoms satellites by 2024, Eutelsat currently operates the world's second-largest satellite constellation fleet after SpaceX. For its part, the European Union is working on the deployment of a sovereign constellation of broadband satellites. This project, comprising 300 satellites and christened Iris2, landed on the European Commission's desk on September 2.

This massive occupation of the Earth's orbit by an ever-growing fleet of satellites does, however, raise numerous questions and concerns about the risks associated with collisions and space debris, as well as light pollution of the night sky for astronomical research.

International competition is intensifying for the deployment of satellite constellations into orbit, notes Statista’s Katharina Buchholz.

Satellite constellations – the most well-known being SpaceX’s Starlink – are designed to provide high-speed global Internet access.

Starlink, launched in 2019, had more than 6,300 satellites in service at the beginning of September, out of 12,000 eventually scheduled to be deployed (or even 40,000 according to an announcement of a possible extension of the project).

Amazon meanwhile plans to put more than 3,200 satellites into orbit as part of its rival Kuiper project.

Following the successful launch of two prototypes last year, the American multinational plans to deploy its first commercial satellites for the project in 2025.

You will find more infographics at Statista

Elsewhere in the world, China is also embarking on large-scale satellite Internet infrastructure projects.

At the beginning of August, the state-owned Shanghai Spacecom Satellite Technology (SSST) launched the first 18 satellites of its Qianfan constellation, which could include more than 15,000 satellites by 2030.

Geespace, a subsidiary of the Chinese car manufacturer Geely, announced that its project had 30 satellites in orbit at the beginning of September, out of the nearly 6,000 planned.

In Europe, French satellite operator Eutelsat entered the fixed and mobile broadband market at the end of 2019. With the recent acquisition of the British low-orbit constellation OneWeb, which will have more than 600 active telecoms satellites by 2024, Eutelsat currently operates the world’s second-largest satellite constellation fleet after SpaceX. For its part, the European Union is working on the deployment of a sovereign constellation of broadband satellites. This project, comprising 300 satellites and christened Iris2, landed on the European Commission’s desk on September 2.

This massive occupation of the Earth’s orbit by an ever-growing fleet of satellites does, however, raise numerous questions and concerns about the risks associated with collisions and space debris, as well as light pollution of the night sky for astronomical research.

Loading…