–>

July 27, 2022

Pew Research recently released a poll showing a significant drop in the public’s trust in science — specifically, medical science. While the “trust trend” towards science has been downward for a while, the COVID-19 pandemic surfaced the issue in ways harder to ignore and exacerbated the trend.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

The results of this poll lead to two questions: Why is trust in science dropping? What can we do about it?

In a recent series of articles in Ubiquity, a publication of the Association of Computing Machinery (ACM), one article points out how much more complex science has become, using mathematical science as an example. One measure of this increasing complexity is the declining number of single-author papers and the increasing number of papers written by interdisciplinary teams. According to the article, increasing complexity reduces trust in science in two ways.

First, increasing complexity makes it harder to understand the results of science. The average person just doesn’t have the training or knowledge to parse scientific papers, and people don’t trust what they cannot understand. Increasing complexity doesn’t seem a likely culprit for the declining trust in science, however — it’s always easy to blame your audience for not understanding you. Still, it’s rarely the audience’s fault.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Second, increasing complexity reduces our ability to falsify results. Theories are proposed and accepted as truth, only to be overturned years — or worse, days — later, leading to the impression that scientists change their minds a lot and that “science-backed truth” is not really “truth” at all.

While this might play a role in the declining trust in science, it doesn’t seem decisive. Most people accept that science is a process. Things we once believed to be true will be disproven when new experiments are made possible via new techniques because someone finds a flaw in some older experiment, etc.

Another article in this special issue argues trust in science is falling because we aren’t trying hard enough to falsify broad, general claims made under a scientific mantle. The authors use examples from software development, but a recent study expands the problem to the medical field. At least some of the “science-backed” standards used for hospital care seem wasteful at best and harmful to patients at worst.

Trust in science does, however, take a hit when broad scientific claims are used for financial purposes. For instance, a recent article in the Epoch Times describes pharmaceutical companies driving the off-label use of medications for financial gain — even though this can sometimes contribute to patient harm.

The recent COVID-19 vaccines are another potential instance of this. From the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic, medical authorities held out vaccines as the “only” way to move past draconian lockdowns so normal life could resume. However, it turns out the vaccines aren’t very good at preventing the disease from spreading, nor are they very good at preventing death, nor even at reducing symptoms.

When health authorities change the meaning of the word “vaccine” to match what they’ve created, evidence that naturally developed immune reactions are effective is suppressed, and treatments with mixed effectiveness and no known side effects (such as Ivermectin) are labeled “dangerous,” the average person is justified in doubting the sincerity of the medical establishment. Revelations of health officials “earning” hundreds of millions of dollars in patent royalties and record-high pharmaceutical profits make it easy to see how the average person might see “science” as just another rigged game used to make the rich richer at the expense of the middle class and poor.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

But if you really want to damage trust in science, combine assertions untethered from falsifiability with audience blaming and social control.

Masks? Early on, it was clear that they might be helpful in some — but not all — situations. Yet “science says” was used to push universal masking, even while driving in a car or walking in the woods alone.

Social distancing? Policymakers shut down worship services and small businesses, destroying community and economic wealth. After all, faith is an unnecessary chimera in the face of science, and the injection of large amounts of money guided by experts can solve all economic problems.

There was no nuance on these issues, just pure force — and force that appeared to be pushing towards greater centralized control. It shouldn’t be surprising that Anthony Fauci openly lying about masks to reach a social goal reduces the average person’s trust in science.

There was no nuance on these issues, just pure force — and force that appeared to be pushing towards greater centralized control. It shouldn’t be surprising that Anthony Fauci openly lying about masks to reach a social goal reduces the average person’s trust in science.

It’s not so much that “scientists” were making proclamations that often turned out to be untrue during the COVID-19 pandemic. They made these declarations unilaterally, squashed dissent, contradicted common sense, and didn’t appear to care about the consequences.

COVID-19 is just one in a long string of examples. Ever since the dawn of the progressive age, we’ve been told that science-backed engineering has all the answers — that we should “trust the science,” or rather “trust the scientists.” Going back to 1910, for instance, George Melville argued before the American Society of Mechanical Engineers that:

[I]n this “age of the engineer,” (the engineer) should not rest content simply with doing the work which makes for our comfort and happiness, at the command of others, men who are lawyers or simply business men, but that the engineer himself should take a vital and directing part in the administration of affairs.

Give the engineer enough control, and they can reconfigure society to improve everything using techniques grounded in science. The engineer and scientist can look down on the little people, lawyers, and “simple” businessmen, directing society towards a better end.

This is just hubris.

The hubris of scientists extends far beyond public policy. For instance, when Kraus argues that philosophers mistake the nature of “nothing” for thousands of years, it impacts “trust in science.”

The popular press piles on by adding audience blaming into the mix. For instance, one writer claims Republicans don’t accept scientific results while Democrats do, implying Republicans aren’t rational. Others posit a rural/city divide rather than a Republican/Democrat divide, arguing the problem is that rural folks are ignorant of how science works. The AP quotes “famed astrophysicist Neil deGrasse Tyson” as saying, “The struggle continues, trying to get the general public to embrace all of the science the way they unwittingly embrace the science in their smartphones.”

Is it any wonder anyone who didn’t start with absolute trust in centralized decision-making via experts might experience the COVID-19 roller-coaster ride and come away a little sick? Is the partisan divide over “trust in science” all that surprising?

How can we rebuild trust in science?

It’s tempting to try and formulate some public policy to solve the problem. Maybe there is some law legislators can pass, and some agency can be tasked with enforcing to tamp down broad scientific claims made for financial gain. Our recent experience with COVID-19, and the pharmaceutical industry at large, however, should dampen our expectations in this regard. Where power can be converted to money and leveraged into more power, it will be. The global climate change industry should reinforce our belief that people will accrue power and money to themselves despite increasingly clear evidence that their beliefs and policies are actively destroying lives.

The progressive mindset holds that humans are perfectible through government action or education. Experience teaches us otherwise.

Scientists should have a little more humility, but there’s no practical way to effect this change.

Maybe Tyson is onto something about audience education — although not in the way he wants to argue. We don’t need more education to convince people to accept everything any scientist might say as truth. We need to learn to apply the things we know to claims made in the name of science more carefully.

We must learn to separate what the scientific method is competent to show and what any individual scientist (or group of scientists), say. Bacon’s argument that we should “trust in proportion to the evidence” applies directly against broad scientific claims (much more than it applies in judging the possibility of miracles).

Being realistic about science, and what science can accomplish, would go a long way towards restoring trust in science — or rather, scientists.

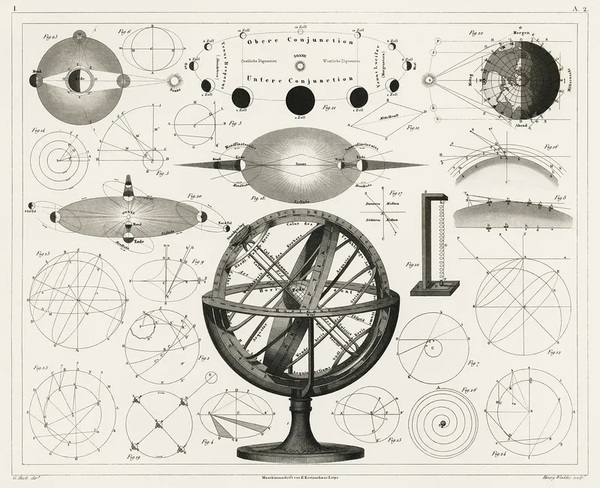

Image: RawPixel.com

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>