Authored by Ron Stoeferle via GoldSwitzerland.com,

1) Bonds are no longer the antifragile portfolio foundation

2022 has been a highly unpleasant year for bonds so far. Over the course of the year, 30-year US Treasuries, for example, fell by around 45%, 10-year US Treasuries by around 18% and German Bunds by around 19%. One of our central theses of the In Gold We Trust reports of the past years is now likely to come true: (government) bonds are no longer the antifragile portfolio foundation they have been over the past 40 years.

By their very nature, the price declines are particularly sharp for bonds with particularly long maturities. The second of the two 100-year Austrian government bonds issued so far has been anything but a good deal. It was issued in 2020 with a coupon of a measly 0.850% and an issue yield of 0.880%. This EUR 2bn bond was oversubscribed 12 times (!!!) when it was issued, which must have made the finance minister pretty happy. However, with inflation now running at more than 10.0%, investors are facing significant losses. The price loss since the issue is now around 62%, from the interim high in the fall of 2020, the minus is even around 70%. The chart is more reminiscent of a volatile junior miner than of supposedly safe government bonds. Many investors have thus had to learn painfully what duration risk means in practice.

2) The negative correlation of stocks and bonds is a myth

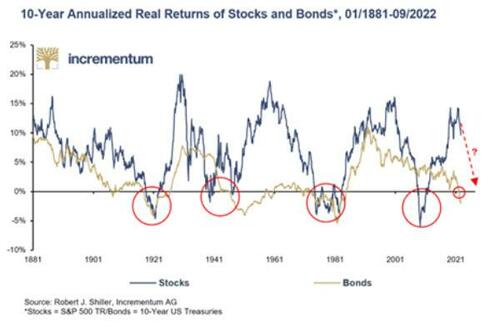

For a long time, the number combination 60/40 was considered an unarguable certainty, almost the holy grail of asset management. A portfolio with a 60% share of equities and a 40% share of bonds would ensure capital growth with manageable risk. But what was considered an eternal truth turns out to be a wealth-threatening myth upon closer inspection. The following chart shows the 10-year annualized real return of stocks (S&P 500 TR) and bonds (10-year US Treasuries) over the past 140 years.

It is noteworthy that the returns are largely symmetrical, suggesting a positive correlation between the two asset classes over the longer term. But while equities are still yielding high returns, the annualized real return on bonds is in negative territory for the first time in almost 40 years.

In the past 140 years, stock returns have only slipped into negative territory four times. The triggers were the two world wars, stagflation in the 1970s and the financial crisis of 2007/08. And each time before the long-term return collapsed, the stock market had previously been in a phase of euphoria, characterized by annualized returns of well over 10% in some cases.

However, the negative correlation is the exception rather than the rule when viewed over the long term. For example, the correlation between stocks and bonds in the US has been slightly positive in 70 of the last 100 years. The decisive factor for the negative correlation in the last 30 years was primarily the low inflationary pressure or the decreasing inflation volatility in the course of the Great Moderation.

3) The positive correlation of bonds and equities has become a problem

So what are actually the consequences, e.g. for mixed portfolios or risk parity investment strategies, if the positive correlation between equities and bonds continues? Stock-bond correlation regimes are stable for a long time, but can reverse rapidly – usually in response to higher inflation rates. The bulk of today’s market participants can hardly imagine the impact of a possible reversal of the correlation, because many investment concepts are built on a low or negative correlation between the two main asset classes.

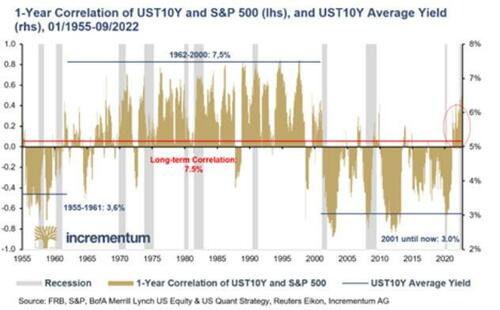

The chart below shows the one-year rolling correlation between 10-year US Treasury bonds and the S&P 500, as well as the average yield on 10-year Treasuries.

One can clearly see that the 1-year correlation has recently turned into positive territory. Since 1955, the correlation coefficient between equities and bonds in the US has been around -0.033, which, when looking at the period as a whole, indicates that the two asset classes are virtually uncorrelated. On the other hand, when looking at individual time periods, we find that stocks and bonds tended to be uncorrelated in exceptional cases. Between 1960 and 2000, when high (nominal) interest rates influenced market activity for long periods, the correlation coefficient was mostly above 0.2, while in an environment of low inflation and interest rates it was mostly below -0.2. Currently, inflation is thus again positively influencing correlation properties, which is probably causing heated discussions at asset allocation committees and sleepless nights for portfolio managers.

4) The situation on the bond markets could soon become precarious

In the US, demand for US Treasuries from the Federal Reserve, US banks and foreign institutions is negative for the first time in at least 10 years each. This collapse in demand is occurring while the US deficit in fiscal year 2021/2022, which ended in late September, was significantly larger at USD 1.4trn than in the pre-Covid-19 fiscal year 2018/2019 with just under USD 1trn. In combination with the expected further interest rate hikes and the continuation of quantitative tightening (QT), this should give bond yields a further boost, at least until the investment models and algorithms that rely on perpetual disinflation face collapse.

On this side of the Atlantic, the situation is even more precarious. On September 28, the Bank of England intervened massively in the British bond market to prevent a Lehman 2.0. The sharp fall in bond prices put British pension funds in a difficult position because of the margin calls due. Two weeks later, the relief owed to the intervention was already gone. In any case, the Bank of England has shown that it will at least interrupt its tightening course in the event of a systemic risk.

This intervention is also due to the fact that mark-to-market losses on derivatives linked to liability-driven investments (LDI) could amount to over GBP 125bn, according to an estimate by JP Morgan. This is equivalent to around 6% of UK GDP.

5) Gold as a stabilizer of the 60/40 portfolio

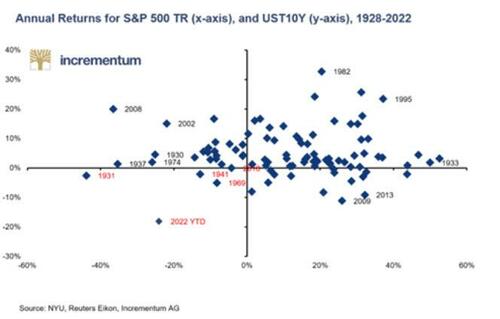

For a large proportion of mixed portfolios, simultaneously falling stocks and bonds are the absolute worst-case scenario. However, in the last 90 years, there have only been four years in which both US stocks and bonds had negative annual performance in the same year. Currently, all indications are that 2022 could be the fifth year.

In two of the four previous cases, 1931 and 1969, a dramatic devaluation of currencies against gold followed. In 1931, sharp declines in stocks and bonds led to Roosevelt’s devaluation of the US dollar against gold by 70% three years later. In 1969, it took only two years for the US to be forced to abandon the gold standard. What will happen this time? What exactly will happen, we do not yet know. But that something historic will happen is likely.

It can be seen that inflation played a central role in all the cases mentioned. For it is not only assets that are devalued by inflation, but also the business models of many companies.

The decoupling between gold and bonds that we announced in previous years has thus taken place in recent months. The bond market and the gold market are sending the same message: deflation or disinflation are no longer the biggest threat to portfolios, inflation is the new reality.

And one thing is certain: the stagflation that is now setting in will not be overcome with a classic 60/40 portfolio. Not only the historical performance of gold, silver and commodities in past periods of stagflation argue for a correspondingly higher weighting of these assets than under normal circumstances. The relative valuation of technology companies to commodity producers is also an argument for a countercyclical investment in the latter. Market strategists at BofA coined the term FAANG 2.0 early on in anticipation of the turnaround:

-

Fuels

-

Aerospace

-

Agriculture

-

Nuclear and Renewables

-

Gold and Metals/Minerals

It may sound surprising at first, but recessions are typically a positive environment for gold. As our analysis in the In Gold We Trust report 2019 has shown, periods when the bear dominates the markets and the real economy are bullish times for gold. Looking at performance over the entire recession cycle, it is notable that gold saw significant average price gains in each of the four recession phases – Phase 1: Entry Phase, Phase 2: Unofficial Recession, Phase 3: Official Recession, Phase 4: Last Quarter of Recession – in both US dollar and euro terms. By contrast, equities – as measured by the S&P 500 – were only able to post significant gains in the final phase of the recession. Gold was thus able to compensate excellently for the equity losses in the early phases of the recession. Moreover, it is noticeable that gold performed on average all the stronger, the higher the price losses of the S&P 500 were.

In summary, gold has largely been able to cushion stock price losses during recessions. For bonds, the classic equity diversifier, on the other hand, things look less good. High levels of debt, the zombification of the economy, and sharp bond price declines as a result of soaring interest rates not only diminish the potential of bonds as an equity corrective, but completely rob bonds of this characteristic.

If the relationship between equities and bonds is now actually reversed on a sustained basis, the basis of the 60/40 portfolio – namely a negative correlation between equities and bonds – would be structurally and thus longer-term removed. The fundamental question would then arise as to which asset would take the scepter from Treasuries. Gold, at any rate, would be a hot candidate. And in our opinion, it is high time to ask this question and act accordingly.

Authored by Ron Stoeferle via GoldSwitzerland.com,

1) Bonds are no longer the antifragile portfolio foundation

2022 has been a highly unpleasant year for bonds so far. Over the course of the year, 30-year US Treasuries, for example, fell by around 45%, 10-year US Treasuries by around 18% and German Bunds by around 19%. One of our central theses of the In Gold We Trust reports of the past years is now likely to come true: (government) bonds are no longer the antifragile portfolio foundation they have been over the past 40 years.

By their very nature, the price declines are particularly sharp for bonds with particularly long maturities. The second of the two 100-year Austrian government bonds issued so far has been anything but a good deal. It was issued in 2020 with a coupon of a measly 0.850% and an issue yield of 0.880%. This EUR 2bn bond was oversubscribed 12 times (!!!) when it was issued, which must have made the finance minister pretty happy. However, with inflation now running at more than 10.0%, investors are facing significant losses. The price loss since the issue is now around 62%, from the interim high in the fall of 2020, the minus is even around 70%. The chart is more reminiscent of a volatile junior miner than of supposedly safe government bonds. Many investors have thus had to learn painfully what duration risk means in practice.

2) The negative correlation of stocks and bonds is a myth

For a long time, the number combination 60/40 was considered an unarguable certainty, almost the holy grail of asset management. A portfolio with a 60% share of equities and a 40% share of bonds would ensure capital growth with manageable risk. But what was considered an eternal truth turns out to be a wealth-threatening myth upon closer inspection. The following chart shows the 10-year annualized real return of stocks (S&P 500 TR) and bonds (10-year US Treasuries) over the past 140 years.

It is noteworthy that the returns are largely symmetrical, suggesting a positive correlation between the two asset classes over the longer term. But while equities are still yielding high returns, the annualized real return on bonds is in negative territory for the first time in almost 40 years.

In the past 140 years, stock returns have only slipped into negative territory four times. The triggers were the two world wars, stagflation in the 1970s and the financial crisis of 2007/08. And each time before the long-term return collapsed, the stock market had previously been in a phase of euphoria, characterized by annualized returns of well over 10% in some cases.

However, the negative correlation is the exception rather than the rule when viewed over the long term. For example, the correlation between stocks and bonds in the US has been slightly positive in 70 of the last 100 years. The decisive factor for the negative correlation in the last 30 years was primarily the low inflationary pressure or the decreasing inflation volatility in the course of the Great Moderation.

3) The positive correlation of bonds and equities has become a problem

So what are actually the consequences, e.g. for mixed portfolios or risk parity investment strategies, if the positive correlation between equities and bonds continues? Stock-bond correlation regimes are stable for a long time, but can reverse rapidly – usually in response to higher inflation rates. The bulk of today’s market participants can hardly imagine the impact of a possible reversal of the correlation, because many investment concepts are built on a low or negative correlation between the two main asset classes.

The chart below shows the one-year rolling correlation between 10-year US Treasury bonds and the S&P 500, as well as the average yield on 10-year Treasuries.

One can clearly see that the 1-year correlation has recently turned into positive territory. Since 1955, the correlation coefficient between equities and bonds in the US has been around -0.033, which, when looking at the period as a whole, indicates that the two asset classes are virtually uncorrelated. On the other hand, when looking at individual time periods, we find that stocks and bonds tended to be uncorrelated in exceptional cases. Between 1960 and 2000, when high (nominal) interest rates influenced market activity for long periods, the correlation coefficient was mostly above 0.2, while in an environment of low inflation and interest rates it was mostly below -0.2. Currently, inflation is thus again positively influencing correlation properties, which is probably causing heated discussions at asset allocation committees and sleepless nights for portfolio managers.

4) The situation on the bond markets could soon become precarious

In the US, demand for US Treasuries from the Federal Reserve, US banks and foreign institutions is negative for the first time in at least 10 years each. This collapse in demand is occurring while the US deficit in fiscal year 2021/2022, which ended in late September, was significantly larger at USD 1.4trn than in the pre-Covid-19 fiscal year 2018/2019 with just under USD 1trn. In combination with the expected further interest rate hikes and the continuation of quantitative tightening (QT), this should give bond yields a further boost, at least until the investment models and algorithms that rely on perpetual disinflation face collapse.

On this side of the Atlantic, the situation is even more precarious. On September 28, the Bank of England intervened massively in the British bond market to prevent a Lehman 2.0. The sharp fall in bond prices put British pension funds in a difficult position because of the margin calls due. Two weeks later, the relief owed to the intervention was already gone. In any case, the Bank of England has shown that it will at least interrupt its tightening course in the event of a systemic risk.

This intervention is also due to the fact that mark-to-market losses on derivatives linked to liability-driven investments (LDI) could amount to over GBP 125bn, according to an estimate by JP Morgan. This is equivalent to around 6% of UK GDP.

5) Gold as a stabilizer of the 60/40 portfolio

For a large proportion of mixed portfolios, simultaneously falling stocks and bonds are the absolute worst-case scenario. However, in the last 90 years, there have only been four years in which both US stocks and bonds had negative annual performance in the same year. Currently, all indications are that 2022 could be the fifth year.

In two of the four previous cases, 1931 and 1969, a dramatic devaluation of currencies against gold followed. In 1931, sharp declines in stocks and bonds led to Roosevelt’s devaluation of the US dollar against gold by 70% three years later. In 1969, it took only two years for the US to be forced to abandon the gold standard. What will happen this time? What exactly will happen, we do not yet know. But that something historic will happen is likely.

It can be seen that inflation played a central role in all the cases mentioned. For it is not only assets that are devalued by inflation, but also the business models of many companies.

The decoupling between gold and bonds that we announced in previous years has thus taken place in recent months. The bond market and the gold market are sending the same message: deflation or disinflation are no longer the biggest threat to portfolios, inflation is the new reality.

And one thing is certain: the stagflation that is now setting in will not be overcome with a classic 60/40 portfolio. Not only the historical performance of gold, silver and commodities in past periods of stagflation argue for a correspondingly higher weighting of these assets than under normal circumstances. The relative valuation of technology companies to commodity producers is also an argument for a countercyclical investment in the latter. Market strategists at BofA coined the term FAANG 2.0 early on in anticipation of the turnaround:

-

Fuels

-

Aerospace

-

Agriculture

-

Nuclear and Renewables

-

Gold and Metals/Minerals

It may sound surprising at first, but recessions are typically a positive environment for gold. As our analysis in the In Gold We Trust report 2019 has shown, periods when the bear dominates the markets and the real economy are bullish times for gold. Looking at performance over the entire recession cycle, it is notable that gold saw significant average price gains in each of the four recession phases – Phase 1: Entry Phase, Phase 2: Unofficial Recession, Phase 3: Official Recession, Phase 4: Last Quarter of Recession – in both US dollar and euro terms. By contrast, equities – as measured by the S&P 500 – were only able to post significant gains in the final phase of the recession. Gold was thus able to compensate excellently for the equity losses in the early phases of the recession. Moreover, it is noticeable that gold performed on average all the stronger, the higher the price losses of the S&P 500 were.

In summary, gold has largely been able to cushion stock price losses during recessions. For bonds, the classic equity diversifier, on the other hand, things look less good. High levels of debt, the zombification of the economy, and sharp bond price declines as a result of soaring interest rates not only diminish the potential of bonds as an equity corrective, but completely rob bonds of this characteristic.

If the relationship between equities and bonds is now actually reversed on a sustained basis, the basis of the 60/40 portfolio – namely a negative correlation between equities and bonds – would be structurally and thus longer-term removed. The fundamental question would then arise as to which asset would take the scepter from Treasuries. Gold, at any rate, would be a hot candidate. And in our opinion, it is high time to ask this question and act accordingly.