An attorney seeking permission to trademark the phrase “Trump too small” and print it on T-shirts for profit will have his First Amendment case weighed by the Supreme Court on Wednesday.

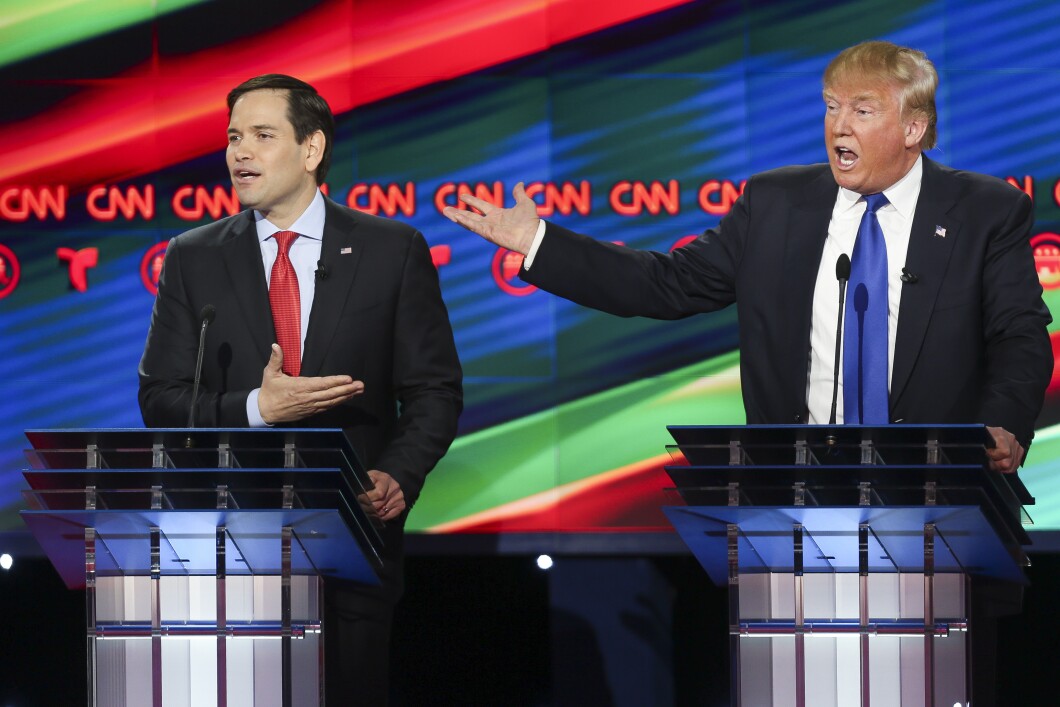

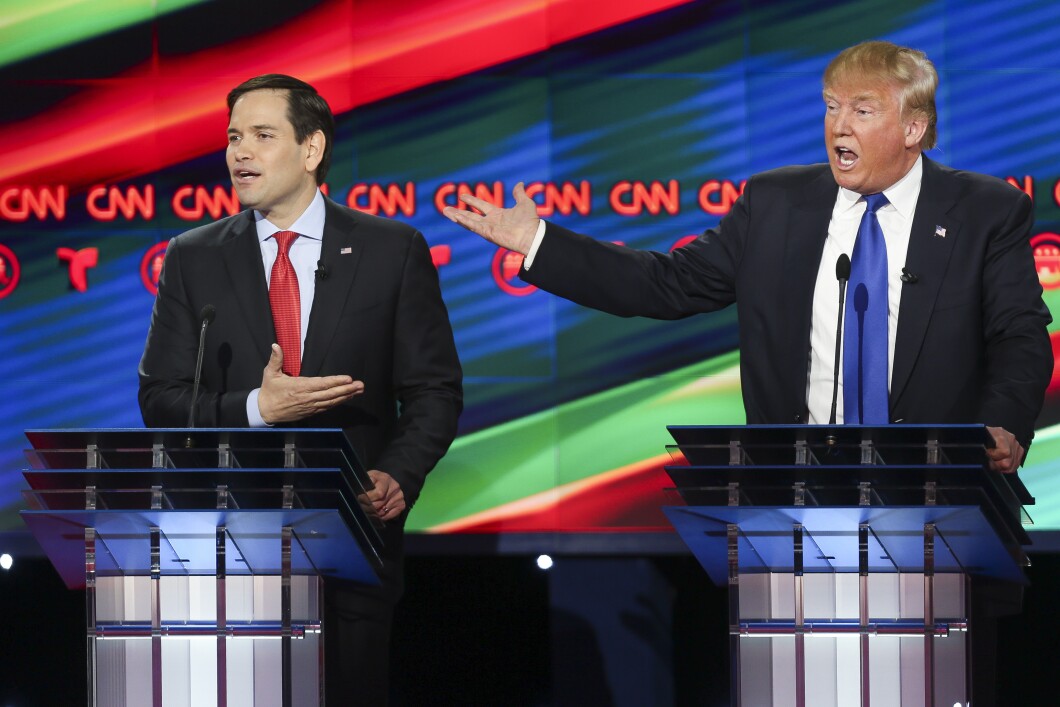

The nine justices will hear arguments over attorney Steve Elster’s bid to trademark the phrase, which originates from the 2016 primary season when the size of then-candidate Donald Trump‘s hands became a humorous rebuttal from his then-primary opponent Sen. Marco Rubio (R-FL).

LIBERAL DC AG WITH TIES TO DARK-MONEY GIANT ACCUSED OF ‘WEAPONIZING’ POWER TO TARGET CONSERVATIVES

Rubio aimed to knock his political opponent down a peg during a campaign stop after Trump had recently coined his characterization of him, “Little Marco.”

“You know what they say about men with small hands,” Rubio said then. Trump later fired back at Rubio’s rebuttal at the next presidential debate, showing his hands to the audience and declaring, “I guarantee you there’s no problem.”

That notorious exchange prompted Elster to create shirts and other merchandise sporting the phrase “Trump too small.” The attorney also planned to include an image of a lewd hand gesture as commentary over the “smallness of Donald Trump’s overall approach to governing as president of the United States.”

Fara Sunderji, a trademark attorney with Dorsey & Whitney, told the Washington Examiner the “outward appearances” of the case shouldn’t be construed as a case about Trump nor the “size of his policies (or body parts.)”

“This is a case about the intersection between trademark law, the First Amendment, rights of privacy, rights of publicity, and political criticisms,” Sunderji said, adding the case presents an opportunity to decide if the denial of trademark registrations restricts speech because the act of the denial would be “chilling.”

When Elster went to the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office to register his idea, the request was denied. The office pointed to the Lanham Act of 1946, which blocks marks on public officials’ names without their consent to avoid confusion from consumers who may think the merchandise was tied to Trump himself.

The U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit eventually ruled against the trademark office in a February 2022 decision, holding the office’s denial violated Elster’s free speech rights under the First Amendment.

“The Federal Circuit, in its prior decision, approached the case from the following angle: ‘The question here is whether the government has an interest in limiting speech on privacy or publicity grounds if that speech involves criticism of government officials—speech that is otherwise at the heart of the First Amendment,’” Sunderji said. “To be clear, the Federal Circuit held that the denial of a trademark registration is discrimination of speech because denying registration disfavors the speech. Thus, the First Amendment is at issue.”

The Justice Department later asked the Supreme Court to take up the case, saying in court filings that for decades, the trademark office has refused to register trademarks that incorporate the name of a living person absent written consent.

Aaron Johnson, a partner at Lewis Roca, told the Washington Examiner the high court’s case comes at a time when the justices have written recent decisions that found other restrictions of trademark registration were void due to the First Amendment, including “the prohibition on trademarks that ‘disparage … or bring … into contempt or disrepute’ any ‘persons, living or dead,’ and the prohibition on trademarks that are ‘immoral or scandalous.'”

However, a June decision over a Jack Daniel’s lawsuit against a dog chew toy company’s parody whiskey bottles dealt a blow to a canine accessory company when a unanimous Supreme Court reversed a lower court decision that said the parody toy was “non-commercial” and enjoyed First Amendment protection. The high court still upheld the precedent that the appeals court used to rule in favor of the toy company, a move that would have granted trademark holders a broad ability to sue companies that parody their marks on consumer products.

Elster contends that the 1946 law “effectively precludes the registration of any mark that criticizes public figures – even as it allows them to register their own positive messages about themselves.” He posits examples such as the trademark office allowing “Joe 2020” and “Hillary for America” but not permitting “No Joe in 2024” or “Hillary for Prison 2016” under the law.

Golden Gate University School of Law professor Samuel Ernst wrote an amicus brief in support of Elster that described the government’s position as a “heckler’s veto” for politicians seeking to silence trademarks that are critical of them, also arguing that altering the law wouldn’t create marketplace confusion.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

“Nobody would be confused into believing that Donald Trump is selling T-shirts accusing him of being too small,” Ernst told Reuters.

The justices will likely present numerous hypothetical examples for the parties to discuss on Wednesday during oral arguments in a bid to test whether the 1946 law is as chilling as Elster says it is. A decision in the case is expected by the end of June next year.