Authored by Peter Tchir via Academy Securities,

As I put pen to paper (or fingers to keypad), I can’t help but wonder if this is the hill that I want to die on?

There is so much uncertainty surrounding the banking developments last week. The only things that I know for certain are that SIVB ended the previous week at $284.39 and was halted before market open on Friday at $105.95 (and is supposedly much lower since). SI, not to be confused with SIVB, closed on February 28 at $13.91 and closed on March 10 at $2.53. That is what we know for certain. We also know that KRE, a $2.13 billion market cap S&P Regional Banking ETF, saw daily trading volume spike from an average of 8.7 million sharesto 97 million shares on Friday. In addition, its market cap dropped 16% last week (let’s call this the “mid bank” index). XLF, a “big financial” ETF, fell 8.5% last week on volume that “only” tripled, but it is exposed to financials other than “big banks”.

The prudent thing is to run away and wait for clarity. That is especially true when there is so much misinformation and even “FUD” (the term crypto people like to use when they disagree with someone’s negative crypto view) that it is almost imperative to stay away from this topic. However, I keep thinking of the phrase “The Lord Hates a Coward”, so let’s dive right in.

The Disruptive Economy

Before looking to the banks and the banking system, I feel it is absolutely necessary to highlight our focus on the “Disruptive Economy”. We believe that it played a large role in not just markets, but the broader economy for the past several years. We’ve used a “broad” definition of disruptive that encompassed some big tech, but also (and far more importantly) the entirety of public and private companies and their investors. In addition, we included crypto and crypto related businesses in that mix. That has led to several important conclusions (or at least thoughts) on our side:

-

The economy and inflation were far more influenced by the disruptive economy than traditional economists acknowledged. See the Rise & Fall of Inflation Factors or the Circular Error in Disruption section from our 2023 Outlook. If the events of the past few weeks don’t have a circularity to them, I don’t know what does.

-

The Disruptive Portfolio and the attitude of many disruptive investors seemed very different from that of “traditional” investors. We are seeing some of that play out here, not just within the institutions, but within their customer bases as well.

-

Finally, as we’ve written, discussed, and even said on national TV, our best comparison is that this is like energy in 2015/2016, but the theme of “disruption” is at the epicenter of this problem! In 2015, the closer you were to energy, the more likely you were to get burned (pun intended). Not just by owning the companies themselves, but by owning companies serving those energy businesses (and the overall regions). This includes the local banks! I continue to believe that the closer you are to “disruption”, the chances are higher for further downside (even more than a year later). As you move away from that “epicenter”, the problems are smaller and might not even be felt.

-

There is one encouraging thing that I cannot resist mentioning given this line of thinking. A certain high yield ETF dropped 20% from the middle of 2014 to its low on February 11, 2016 (mostly due to energy and commodity exposure). About a month later, as the tide was already turning, a HY ETF that excluded energy companies was announced. Maybe we haven’t hit rock bottom in this particular episode, but the contrarian in me is attracted to mid banks after the events of this past week.

-

Now that we’ve set the table with that recap of our views on disruption, we can move on to another table setting section.

Not My First Rodeo

I’ve been on both sides of highly controversial issues. I’m not always bullish, and if anything, I am more often than not bearish. It’s my nature, which is probably why I liked trading credit derivatives on junk bonds and indices.

-

I hated the CPDO product (Constant Proportion Default Obligations). It took leverage on something that was BBB and made it AAA. Yes, this is where you put leverage on something and received a better rating compared to owning it outright. Seemed nonsensical, and it was, but the “math” worked. However, the math had a major “flaw” in that it ignored how many companies might see spreads widen dramatically, then lose their IG rating, and not be put back into the relevant indices when (if) they recovered. We proved that portfolios constructed in the past (2000s) would have triggered this product (circa 2006 or so). The product was so wildly profitable. You got to charge people to leverage something that was BBB (and already profitable) and had a customer base of AAA only buyers. Anyways, on a painful call to the big boss’s office I was told to stop fighting something that I was so “obviously” wrong about.

-

Roadmap to IG 200 (and the accompanying IG 200 hats). It was controversial, not quite right (only got to 198), and then I overstayed my welcome when I faded the post “JPM saving Bear” rally in CDS far too early (which has also left scars).

-

Could a VIX ETF Go Poof in a Day? I once worked with a reporter who was so passionate about a story that he fought the editors and detractors until he got the piece published. That made the follow-on piece One Did Go Poof so sweet!

I’ve also been comfortable taking the bull case. In fact, saying “buy Jefferies” in response to Steph Ruhle’s question (back when she was still on Bloomberg TV) created quite a soundbite for my independent research company. It actually turned out to be quite right (despite all the poorly thoughtout comparisons to MF Global).

More recently, at Academy, we championed credit by touting 2019 as the Year of the Debt Diet, having published a piece questioning the punishment that GE credit spreads were taking just a month or two before that.

Writing that GE piece feels eerily similar to what I’m about to embark on today. I can only hope that the results are as timely and as poignant. I’ve gotten plenty of things wrong, otherwise I’d be writing these missives from some exotic private island, but let’s do this and see where we come out!

Bank Runs!

I hate even writing those two words! It seems incredibly flammable. Like shouting fire in a crowded theater. I’m not even sure who I keep checking for over my shoulder when I write or say “bank runs”. Is it compliance? Is it the regulators? I don’t know, but this is a term that I rarely use because I think that it is shocking and dangerous, but I couldn’t figure out a better way to start the analysis of what is going on because this phrase is coming up with more frequency.

Banks are “strange” beasts. In some ways their business model is so simple (take deposits, lend money, and make the spread in between). But not only is that simplistic, it misses the key ingredient, leverage. You cannot take enough deposits and lend them out “one to one” to make a reasonable return.

VCSH, a 1 to 5-year corporate bond ETF, has a spread of about 110 bps. No one is buying a bank making 1%, so it needs leverage. Maybe the bank could take a lot of duration risk (I don’t know why it would, since banks learned a lot during the S&L crisis). But even with duration risk, banks aren’t an interesting thing without leverage!

So, we will talk about leverage, at least initially.

Banks have capital from several different sources at various levels of the capital structure.

-

Equity capital. This is what drives everything. The amount of assets a bank can hold on its books is largely determined by its equity capital (and portfolio quality).

-

Subordinated capital. Not as good as equity capital, but it enables the bank to do more than it could with just regular debt, and it is at a lower cost than raising equity.

-

Debt.

-

Deposits. Deposits are generally the “holy grail” of the bank balance sheet (post Covid banks were turning away deposits, but that was unique). You pay far less interest on funds on deposit than other forms of borrowing. They are typically viewed as “sticky”. People keep money in a bank account for a lot of reasons, probably the least of which is the interest they are earning. People (and companies) do most of their transactions through banks (and credit cards). The bank account is the “home base” of financial activities and thus tends to be more stable than other forms of debt which are more subject to market vagaries.

-

Bonds. At the risk of annoying some of our banking clients, I think one of the “best” things that came out of the GFC (on the regulatory front) was rules to largely enforce longer-dated borrowing. There is a cost to banks (and everyone) to switch to longerdated funding. It is generally far cheaper to borrow overnight than it is for 30 years (though with our current yield curve, that isn’t as obvious today as it normally is). The problem with that is you need to fund yourself every night. Banks could argue that this should be part of their risk decision, but stricter rules were imposed anyway. Since we saw what happened when bank credit quality gets called into question (ability to borrow can dry up quickly), this was a logical way to protect the system. Yes, it is a cost to banks, but I think that it really promoted a new level of “safety” on the funding side. I disagree with much of Dodd Frank and think that the Volcker Rule could only have been written by someone who had never seen a trading floor, let alone stepped onto one. One of the first things that I learned about the bond business was when I asked why almost every high yield bond was a 10 non-call 5. The answer was outrageously simple. “Because investors need to be compensated for at least 5 years of lending to the company in their current state and the company needs a 5-year window where their business is good enough (or the market is strong enough) that they can re-fi”. So, yes, I like less refinancing risk.

-

A bank run is when depositors and lenders stop funding the bank, which normally occurs due to credit quality concerns!

When I think of a bank run, I think of a fear that the bank’s assets are not solid and would incur significant losses (if sold today or those losses would be realized over time as borrowers failed to pay the bank back). Accrual accounting, not held for sale, etc. are accounting provisions used to dampen volatility in asset prices on the bank’s balance sheet. There is a difference between a loan going down in price a bit because of rates (or overall market concern) and the likelihood of that loan getting paid off. During the GFC, it was apparent that massive amounts of mortgage debt were impaired and were never coming back. Again, I think that the regulators have done a very good job with CCAR (Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review). It incorporates many tough scenarios, but what I like most about it is that it is a “random” day, picked after the fact. Bank capital rules were almost exclusively quarterly and annual. There were massive quarter end trades done by banks. There were huge year-end trades done (especially between Asian and North American banks which had different year-ends) and these trades were less sensitive to certain annual measures. CCAR does a lot to capture the risk side of the balance sheet. It is designed so that “we” (collectively) can sleep at night “knowing” that banks are safe and won’t go through another GFC. Some of this may be questioned in light of recent events and disclosures, but I for one suspect that CCAR is serving its purpose, which is one reason why I’m heavily leaning towards this being isolated and not an industrywide issue.

On a cursory glance and from what I’ve read, there were some issues linked to the performance of “safe” (from a credit perspective) long-duration assets. From what I’ve seen so far, I’m surprised by the duration risk that was being run. I’m a big believer in “match funding” as much as possible. That tends to reduce NIM, but also greatly reduces risks, like the ones we seem to be seeing now. Sure, hindsight is 20/20, but that is something that I strongly believe in at all times.

Neither Moody’s nor S&P seemed to see much amiss at SIVB (no material rating action for years, until this past week). It seemed like business as usual, at least from a NRSRO (Nationally Recognized Statistical Ratings Organization) perspective.

I will attempt to demonstrate that this is a unique situation and is linked more to the types of depositors that these banks had than to anything that is reflective of a broad trend across the industry.

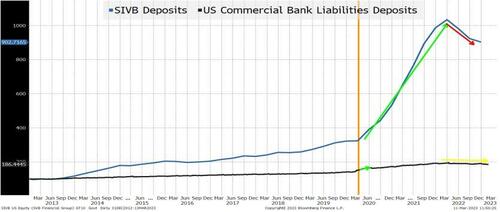

We start with deposits at the SIVB entities versus the entire banking system (note: SIVB deposit data is quarterly and last data point was from the end of 2022). You can see a small uptick in bank deposits during Covid relief (small as a percentage, but large in total dollars). SIVB saw their deposit levels more than triple (from $60 billion in March 2020, to a peak of almost $200 billion).

This chart highlights three important things:

-

The deposit growth seems reasonably correlated to value creation in the “disruptive” space (taking the liberty of using ARKK as a representative of that space). It was consistent with the narrative behind this entity.

-

Deposits, in my opinion, started declining because of the industry that this bank caters to, which had been incredibly successfully for decades, but was now burning cash and had less wealth. The initial phases of deposit decline had everything to do with the depositor base and little to do with their portfolio or any other “traditional” trigger.

-

It might also provide some insight into the sort of lending opportunities that were available at the time companies/individuals were making deposits (i.e., disruptive firms).

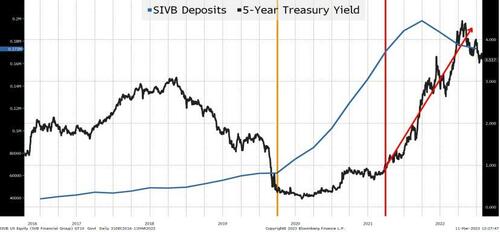

This chart is “problematic” in some ways as you can see the surge in deposits correspond to a period of time when the 5-year Treasury yield was less than 1%. Since deposit rates in the U.S. stayed positive (with very few exceptions) there was relatively little spread to be earned. Taking in huge deposits at a time when yields were very low can be problematic (and let’s not forget the need to leverage).

At this point, I have to admit that how they managed their portfolios also seemed to be contributing to the problem.

These institutions seemed to do two things that are now, in hindsight, problematic.

-

They lent to “disruptive” companies. This is their bread and butter. It is their customer base. It is what made the bank famous. However, I suspect that they had never seen such an influx of money (at a time when valuations were so high and disruptive company growth prospects were unbelievably great). Even with conservative haircuts it may have been difficult to exercise prudence, and without a doubt, other banks and lenders were gunning for their customers! They were the bankers to the “sweet spot” and everyone wanted that business.

-

They seemed to have taken on more duration risk than other banks (I could be wrong here and that would be a flaw in my argument). They were basically increasing in size at a rapid pace in an environment where anything liquid was yielding next to nothing. They were getting money stuffed into deposits at one of the least interesting times for a bank to take deposits (at least in terms of locking in good NIM – Net Interest Margin).

That has now contributed to their decline as the asset side is being called into question!

Why I Think Current Cases are “Unique”

The two banks in question, while different, have some similarities that are unique to them.

Let’s get down to the theory here"

-

A massive surge (on a percentage basis) in deposits. Bank deposits grew everywhere, but the rate of increase more than tripling in a year is unique. While banks had to absorb new deposits in the wake of Covid and stimulus, these institutions saw disproportionate growth as a percentage (and total amount). Tripling from $1 billion to $3 billion seems like an easier task to manage than going from $60 billion to $180 billion. Relatively unique set of circumstances.

-

A highly correlated customer base. Whether Silicon Valley or crypto juggernauts, the customers turned out to be far more correlated than expected. When almost “everything” crypto/disruptive took off, it behaved as one entity (rather than 100s or 1000s of companies and individuals). Potentially there was some geographic concentration, but it is unusual (and unexpected) for such diverse businesses and individuals to be so correlated on the way up and on the way down. Relatively unique set of circumstances.

-

Portfolio selection.

-

Lending to customers is quite normal in banking, which is ultimately a relationship business. It is why certain banks were more exposed to energy for example. Banks, especially community banks, tend to have exposure to their “community”. Less so for regionals and even more less so for the global money-center banks. Community in this case was more about “what the people or companies did” rather than physical proximity (though that plays in as well since the two go hand in hand). I assume that there is some exposure to local real estate, which has also come under pressure since the deposits piled up. The exposure to disruptive/crypto is likely far higher here than in other banks.

-

Rate risk. The chase for yield was alive and well as the money was flooding into banks. This seems like a good time to bring back “5 Circles of Bond Investor Hell.” There are only a few things you can do when you need yield, one of which is to increase duration, which was apparently done here. Hoping the market cheapens would have worked great, but it rarely does and there is immense pressure not to sit on cash, so I’d be shocked if many had the fortitude to do that. It seems like SIVB may have extended duration. Taking more risk than normal is probably somewhat common across banks, though I’m not sure rate risk would have been the preferred method. I lean towards giving up liquidity (most don’t use it) or increasing structure (my theory on AAA CLOs being more difficult to bust than getting a perfect March Madness bracket).

-

5 Circles of Bond Investor Hell

I see the situation as unique because:

-

They had exceptional growth in a compressed timeframe.

-

Growth occurred during an exceptional dearth of yield.

-

Some of their decisions and the nature of their customer base (to whom they lent) may have set them up with a portfolio that was more exposed than others.

-

Customers started withdrawing because they needed the money (nothing to do with anything SIVB was doing).

-

Those withdrawals triggered selling, which turned positions meant for accrual accounting into realized losses! That combination following a period of explosive growth seemed to be what caught the attention of people.

-

Now something that looks more like a “normal” run starts. Losses get exposed. The balance sheet faces more scrutiny. Some clients may get nervous. The cash burn, which started after March 2022, likely continued into Q1 2023 (the last data point was at the end of 2022). This is where we are now and is why everyone is worried about other banks!

I am stuck seeing this as far more unique than systemic, hence the recent selling is overdone!

Some Bad News for All Banks

The banking sector, even if I’m correct, will not get off scot-free.

-

Interest rates on deposits will probably have to get “competitive” more rapidly than they normally would. People covered by the FDIC limits will care less as there is no credit risk to the institution, but recent focus on higher yields across the board will make many consider keeping enough “working capital” at the bank, while owning money market funds or other higher yielding assets (including Certificates of Deposit at many banks). Personally I think that should be SOP and is how I think about my deposits – and no, I’m not trying to get banks to hate me! Those above the FDIC limits are exposed as senior unsecured creditors if a bank fails. The returns paid to senior unsecured creditors are much better than those paid on deposits, but the services provided by banks (anything from LOCs to simple check cashing and enabling payroll and business activities to function seamlessly) have immense value. I could see some banks increasing their payment rates on deposits which would eat into NIM, but that would be a valuation issue, not a credit issue. Bank P/E multiples being too high already don’t keep me up at night. I suspect little of the NIM gets a great multiple in any case, as investors have been expecting banks to slowly raise the amount they pay on deposits.

-

Closer scrutiny to bank portfolios. People far smarter than me (with better tools at their fingertips) are looking at what exposures banks have on their books. Making that analysis more complex will be the fact that many of the exposures (and certainly all of the hedges) will be in derivative books that I think are opaque at best. I would not want to be in charge of a bank that faces the headline “XYZ loaded up on duration during ZIRP” in the coming days. That is the sort of headline that can trigger people taking out deposits. If I believed a lot of banks really extended duration during ZIRP, I would be scared to death right now about recommending banks, but:

-

Asset growth was not that far above normal for most banks.

-

Private debt, credit risk, and structured risk all seem more natural for banks, all of which have been weathering this market better than sovereign debt (assuming the rate risk is taken out, which it should be in my vision of bank risk management).

-

I am fully aware of these two risks, but think that:

-

Most banks are well prepared to deal with both issues and will not face any sort of a run. I am saying this, fully knowing how that “bank run” sentiment can spread like wildfire. You cannot believe how nervous I’ve been writing this report (which is maybe why it is longer than usual) because I do understand how afraid people are and how quickly even a false allegation can trigger negative momentum.

-

Valuations (after the recent shellacking) offer upside in a tricky market environment – both on the equity and credit side of the equation.

The Non-FDIC Insured Depositors

I saw a stat that SIVB has only about 3% of its deposits fully covered by the FDIC (very low compared to most banks). Presumably this is a bank for rich individuals and corporations.

This is the group that is in limbo and I don’t fully understand the next steps.

If you have $100,000,000 on deposit to meet your obligations, how much of that can you access?

In theory, as I understand this:

-

The assets of the bank are worth X.

-

The FDIC depositors (and maybe some other senior stuff) are worth Y.

-

Z is the amount of deposits above the FDIC limits and other senior unsecured debt.

-

If X – Y > Z then there is equity value. I’m not sure I’d write that off yet, but that is just me musing about the subject. I don’t have an opinion and am not basing my overall bank recommendation on it, but it seems to have been left for dead rather quickly (even by panic standards).

-

If X – Y < Z then Z will be impaired and not receive 100 cents on the dollar.

-

Lehman claims, which were classified as unsecured debt because they filed before investment banks became banks under emergency GFC policy, settled at about 20% of par (though they ultimately recovered 100% plus accrued). It isn’t completely irrelevant (it wasn’t a bank), but it also gives us the sense of how complex this can be with financial instruments.

-

Some things in favor of SIVB’s valuations:

-

It seems that much of their portfolio is liquid, making it easier to monetize and start establishing minimal values (and presumably immediate availability) for the unsecured creditors.

-

Their customer base is still a who’s who of the valley and disruptive space and many other banks and financial service companies will want to establish relationships which will help the valuation and/or any necessary sale of these assets.

-

So far it is isolated. If their situation is unique (as I obviously believe it is) then the market has a large, but digestible set of assets to absorb. If this is just the tip of the iceberg, then we are in some serious trouble as there will be more forced selling and huge pools of fixed income “in for the bid”. During the GFC, almost every bank owned too much of the same thing and needed to sell. Remember AIG FP and their super senior protection on corporate credit? That part of their portfolio never sniffed a loss as corporate credit failure was extremely well contained even in the GFC (however, the mortgage super senior was a mess). Overall, recovery rates tend to be higher during good economic times because there are fewer distressed sellers. So far this is a unique case, and that helps maximize value.

Understanding how much access to above FDIC limit deposits companies (and individuals) will have by Monday is crucial for the disruptive companies – more so than for other banks! Access (to at least a portion) is necessary for many to function. I fully expect there to be some contingencies allowing some % access, though I could be wrong.

White Knight Dream?

I would not be shocked to see a “white knight” investor appear for the entire entity (possibly by Monday) because it makes a lot of the mess regarding the unsecured depositors go away (or at least more manageable).

In the early stages of the financial crisis, we saw various entities get absorbed with a nod (if not a gentle push) from the regulators, when only months before these transactions would have faced regulatory opposition.

The “easiest” and least painful way to value the assets might be via an acquisition by one large institution. I see two hurdles/questions facing that “dream”:

-

Will SIVB accept a valuation or will they want to work their way out, quite possibly, attempting to generate cash for equity holders and not just depositors?

-

Will banks, the natural buyer, be worried about their own deposit base too much to attempt an ambitious purchase, even with a nod from the regulators?

I’m convinced that the Fed learned one massive lesson from the GFC (we saw Europe do a semi-decent job with their own debt crisis) - DON’T LET CONFIDENCE IN THE BANKING SECTOR FAIL!!!!

Nothing else really matters. Financial institutions can write “living wills” until the cows come home, but if we get to that point, all bets are off.

If this is isolated (or even if it isn’t), regulators are supposed to be ring-fencing it in because the last thing they need is for “bank run” to become the word of the week. That is hard to walk back, so getting out in front of it is crucial.

Given how quickly they responded after Covid lockdowns (at warp speed relative to the almost plodding behavior back in 2007 and early 2008), there is hope.

I bet there will be a lot of green dots on Bloomberg terminals on Sunday night – I remember being there when $2 dollars/share came across as the price for Bear Stearns (and physically tapping my screen with my finger, thinking the 2 was a typo).

One thing many forget (or don’t know) about the JPM purchase of Bear was that it was accompanied by an immediate and non-contingent guarantee of Bear’s derivative book. Even if the equity deal didn’t consummate, the derivative book was JPM’s. No one ever really explained how that would work, and there wasn’t much (if any) formal guarantee language.

I Like Mid Banks, I Cannot Lie

I also like big banks and small banks and am more scared of admitting that than I am of singing the original lyrics from this song – so yes, I’ve dragged myself to this hill and am going to stand my ground on it!

I did not have bank failure Sundays on my 2023 bingo card (but it does bring back memories)!

Authored by Peter Tchir via Academy Securities,

As I put pen to paper (or fingers to keypad), I can’t help but wonder if this is the hill that I want to die on?

There is so much uncertainty surrounding the banking developments last week. The only things that I know for certain are that SIVB ended the previous week at $284.39 and was halted before market open on Friday at $105.95 (and is supposedly much lower since). SI, not to be confused with SIVB, closed on February 28 at $13.91 and closed on March 10 at $2.53. That is what we know for certain. We also know that KRE, a $2.13 billion market cap S&P Regional Banking ETF, saw daily trading volume spike from an average of 8.7 million sharesto 97 million shares on Friday. In addition, its market cap dropped 16% last week (let’s call this the “mid bank” index). XLF, a “big financial” ETF, fell 8.5% last week on volume that “only” tripled, but it is exposed to financials other than “big banks”.

The prudent thing is to run away and wait for clarity. That is especially true when there is so much misinformation and even “FUD” (the term crypto people like to use when they disagree with someone’s negative crypto view) that it is almost imperative to stay away from this topic. However, I keep thinking of the phrase “The Lord Hates a Coward”, so let’s dive right in.

The Disruptive Economy

Before looking to the banks and the banking system, I feel it is absolutely necessary to highlight our focus on the “Disruptive Economy”. We believe that it played a large role in not just markets, but the broader economy for the past several years. We’ve used a “broad” definition of disruptive that encompassed some big tech, but also (and far more importantly) the entirety of public and private companies and their investors. In addition, we included crypto and crypto related businesses in that mix. That has led to several important conclusions (or at least thoughts) on our side:

-

The economy and inflation were far more influenced by the disruptive economy than traditional economists acknowledged. See the Rise & Fall of Inflation Factors or the Circular Error in Disruption section from our 2023 Outlook. If the events of the past few weeks don’t have a circularity to them, I don’t know what does.

-

The Disruptive Portfolio and the attitude of many disruptive investors seemed very different from that of “traditional” investors. We are seeing some of that play out here, not just within the institutions, but within their customer bases as well.

-

Finally, as we’ve written, discussed, and even said on national TV, our best comparison is that this is like energy in 2015/2016, but the theme of “disruption” is at the epicenter of this problem! In 2015, the closer you were to energy, the more likely you were to get burned (pun intended). Not just by owning the companies themselves, but by owning companies serving those energy businesses (and the overall regions). This includes the local banks! I continue to believe that the closer you are to “disruption”, the chances are higher for further downside (even more than a year later). As you move away from that “epicenter”, the problems are smaller and might not even be felt.

-

There is one encouraging thing that I cannot resist mentioning given this line of thinking. A certain high yield ETF dropped 20% from the middle of 2014 to its low on February 11, 2016 (mostly due to energy and commodity exposure). About a month later, as the tide was already turning, a HY ETF that excluded energy companies was announced. Maybe we haven’t hit rock bottom in this particular episode, but the contrarian in me is attracted to mid banks after the events of this past week.

-

Now that we’ve set the table with that recap of our views on disruption, we can move on to another table setting section.

Not My First Rodeo

I’ve been on both sides of highly controversial issues. I’m not always bullish, and if anything, I am more often than not bearish. It’s my nature, which is probably why I liked trading credit derivatives on junk bonds and indices.

-

I hated the CPDO product (Constant Proportion Default Obligations). It took leverage on something that was BBB and made it AAA. Yes, this is where you put leverage on something and received a better rating compared to owning it outright. Seemed nonsensical, and it was, but the “math” worked. However, the math had a major “flaw” in that it ignored how many companies might see spreads widen dramatically, then lose their IG rating, and not be put back into the relevant indices when (if) they recovered. We proved that portfolios constructed in the past (2000s) would have triggered this product (circa 2006 or so). The product was so wildly profitable. You got to charge people to leverage something that was BBB (and already profitable) and had a customer base of AAA only buyers. Anyways, on a painful call to the big boss’s office I was told to stop fighting something that I was so “obviously” wrong about.

-

Roadmap to IG 200 (and the accompanying IG 200 hats). It was controversial, not quite right (only got to 198), and then I overstayed my welcome when I faded the post “JPM saving Bear” rally in CDS far too early (which has also left scars).

-

Could a VIX ETF Go Poof in a Day? I once worked with a reporter who was so passionate about a story that he fought the editors and detractors until he got the piece published. That made the follow-on piece One Did Go Poof so sweet!

I’ve also been comfortable taking the bull case. In fact, saying “buy Jefferies” in response to Steph Ruhle’s question (back when she was still on Bloomberg TV) created quite a soundbite for my independent research company. It actually turned out to be quite right (despite all the poorly thoughtout comparisons to MF Global).

More recently, at Academy, we championed credit by touting 2019 as the Year of the Debt Diet, having published a piece questioning the punishment that GE credit spreads were taking just a month or two before that.

Writing that GE piece feels eerily similar to what I’m about to embark on today. I can only hope that the results are as timely and as poignant. I’ve gotten plenty of things wrong, otherwise I’d be writing these missives from some exotic private island, but let’s do this and see where we come out!

Bank Runs!

I hate even writing those two words! It seems incredibly flammable. Like shouting fire in a crowded theater. I’m not even sure who I keep checking for over my shoulder when I write or say “bank runs”. Is it compliance? Is it the regulators? I don’t know, but this is a term that I rarely use because I think that it is shocking and dangerous, but I couldn’t figure out a better way to start the analysis of what is going on because this phrase is coming up with more frequency.

Banks are “strange” beasts. In some ways their business model is so simple (take deposits, lend money, and make the spread in between). But not only is that simplistic, it misses the key ingredient, leverage. You cannot take enough deposits and lend them out “one to one” to make a reasonable return.

VCSH, a 1 to 5-year corporate bond ETF, has a spread of about 110 bps. No one is buying a bank making 1%, so it needs leverage. Maybe the bank could take a lot of duration risk (I don’t know why it would, since banks learned a lot during the S&L crisis). But even with duration risk, banks aren’t an interesting thing without leverage!

So, we will talk about leverage, at least initially.

Banks have capital from several different sources at various levels of the capital structure.

-

Equity capital. This is what drives everything. The amount of assets a bank can hold on its books is largely determined by its equity capital (and portfolio quality).

-

Subordinated capital. Not as good as equity capital, but it enables the bank to do more than it could with just regular debt, and it is at a lower cost than raising equity.

-

Debt.

-

Deposits. Deposits are generally the “holy grail” of the bank balance sheet (post Covid banks were turning away deposits, but that was unique). You pay far less interest on funds on deposit than other forms of borrowing. They are typically viewed as “sticky”. People keep money in a bank account for a lot of reasons, probably the least of which is the interest they are earning. People (and companies) do most of their transactions through banks (and credit cards). The bank account is the “home base” of financial activities and thus tends to be more stable than other forms of debt which are more subject to market vagaries.

-

Bonds. At the risk of annoying some of our banking clients, I think one of the “best” things that came out of the GFC (on the regulatory front) was rules to largely enforce longer-dated borrowing. There is a cost to banks (and everyone) to switch to longerdated funding. It is generally far cheaper to borrow overnight than it is for 30 years (though with our current yield curve, that isn’t as obvious today as it normally is). The problem with that is you need to fund yourself every night. Banks could argue that this should be part of their risk decision, but stricter rules were imposed anyway. Since we saw what happened when bank credit quality gets called into question (ability to borrow can dry up quickly), this was a logical way to protect the system. Yes, it is a cost to banks, but I think that it really promoted a new level of “safety” on the funding side. I disagree with much of Dodd Frank and think that the Volcker Rule could only have been written by someone who had never seen a trading floor, let alone stepped onto one. One of the first things that I learned about the bond business was when I asked why almost every high yield bond was a 10 non-call 5. The answer was outrageously simple. “Because investors need to be compensated for at least 5 years of lending to the company in their current state and the company needs a 5-year window where their business is good enough (or the market is strong enough) that they can re-fi”. So, yes, I like less refinancing risk.

-

A bank run is when depositors and lenders stop funding the bank, which normally occurs due to credit quality concerns!

When I think of a bank run, I think of a fear that the bank’s assets are not solid and would incur significant losses (if sold today or those losses would be realized over time as borrowers failed to pay the bank back). Accrual accounting, not held for sale, etc. are accounting provisions used to dampen volatility in asset prices on the bank’s balance sheet. There is a difference between a loan going down in price a bit because of rates (or overall market concern) and the likelihood of that loan getting paid off. During the GFC, it was apparent that massive amounts of mortgage debt were impaired and were never coming back. Again, I think that the regulators have done a very good job with CCAR (Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review). It incorporates many tough scenarios, but what I like most about it is that it is a “random” day, picked after the fact. Bank capital rules were almost exclusively quarterly and annual. There were massive quarter end trades done by banks. There were huge year-end trades done (especially between Asian and North American banks which had different year-ends) and these trades were less sensitive to certain annual measures. CCAR does a lot to capture the risk side of the balance sheet. It is designed so that “we” (collectively) can sleep at night “knowing” that banks are safe and won’t go through another GFC. Some of this may be questioned in light of recent events and disclosures, but I for one suspect that CCAR is serving its purpose, which is one reason why I’m heavily leaning towards this being isolated and not an industrywide issue.

On a cursory glance and from what I’ve read, there were some issues linked to the performance of “safe” (from a credit perspective) long-duration assets. From what I’ve seen so far, I’m surprised by the duration risk that was being run. I’m a big believer in “match funding” as much as possible. That tends to reduce NIM, but also greatly reduces risks, like the ones we seem to be seeing now. Sure, hindsight is 20/20, but that is something that I strongly believe in at all times.

Neither Moody’s nor S&P seemed to see much amiss at SIVB (no material rating action for years, until this past week). It seemed like business as usual, at least from a NRSRO (Nationally Recognized Statistical Ratings Organization) perspective.

I will attempt to demonstrate that this is a unique situation and is linked more to the types of depositors that these banks had than to anything that is reflective of a broad trend across the industry.

We start with deposits at the SIVB entities versus the entire banking system (note: SIVB deposit data is quarterly and last data point was from the end of 2022). You can see a small uptick in bank deposits during Covid relief (small as a percentage, but large in total dollars). SIVB saw their deposit levels more than triple (from $60 billion in March 2020, to a peak of almost $200 billion).

This chart highlights three important things:

-

The deposit growth seems reasonably correlated to value creation in the “disruptive” space (taking the liberty of using ARKK as a representative of that space). It was consistent with the narrative behind this entity.

-

Deposits, in my opinion, started declining because of the industry that this bank caters to, which had been incredibly successfully for decades, but was now burning cash and had less wealth. The initial phases of deposit decline had everything to do with the depositor base and little to do with their portfolio or any other “traditional” trigger.

-

It might also provide some insight into the sort of lending opportunities that were available at the time companies/individuals were making deposits (i.e., disruptive firms).

This chart is “problematic” in some ways as you can see the surge in deposits correspond to a period of time when the 5-year Treasury yield was less than 1%. Since deposit rates in the U.S. stayed positive (with very few exceptions) there was relatively little spread to be earned. Taking in huge deposits at a time when yields were very low can be problematic (and let’s not forget the need to leverage).

At this point, I have to admit that how they managed their portfolios also seemed to be contributing to the problem.

These institutions seemed to do two things that are now, in hindsight, problematic.

-

They lent to “disruptive” companies. This is their bread and butter. It is their customer base. It is what made the bank famous. However, I suspect that they had never seen such an influx of money (at a time when valuations were so high and disruptive company growth prospects were unbelievably great). Even with conservative haircuts it may have been difficult to exercise prudence, and without a doubt, other banks and lenders were gunning for their customers! They were the bankers to the “sweet spot” and everyone wanted that business.

-

They seemed to have taken on more duration risk than other banks (I could be wrong here and that would be a flaw in my argument). They were basically increasing in size at a rapid pace in an environment where anything liquid was yielding next to nothing. They were getting money stuffed into deposits at one of the least interesting times for a bank to take deposits (at least in terms of locking in good NIM – Net Interest Margin).

That has now contributed to their decline as the asset side is being called into question!

Why I Think Current Cases are “Unique”

The two banks in question, while different, have some similarities that are unique to them.

Let’s get down to the theory here”

-

A massive surge (on a percentage basis) in deposits. Bank deposits grew everywhere, but the rate of increase more than tripling in a year is unique. While banks had to absorb new deposits in the wake of Covid and stimulus, these institutions saw disproportionate growth as a percentage (and total amount). Tripling from $1 billion to $3 billion seems like an easier task to manage than going from $60 billion to $180 billion. Relatively unique set of circumstances.

-

A highly correlated customer base. Whether Silicon Valley or crypto juggernauts, the customers turned out to be far more correlated than expected. When almost “everything” crypto/disruptive took off, it behaved as one entity (rather than 100s or 1000s of companies and individuals). Potentially there was some geographic concentration, but it is unusual (and unexpected) for such diverse businesses and individuals to be so correlated on the way up and on the way down. Relatively unique set of circumstances.

-

Portfolio selection.

-

Lending to customers is quite normal in banking, which is ultimately a relationship business. It is why certain banks were more exposed to energy for example. Banks, especially community banks, tend to have exposure to their “community”. Less so for regionals and even more less so for the global money-center banks. Community in this case was more about “what the people or companies did” rather than physical proximity (though that plays in as well since the two go hand in hand). I assume that there is some exposure to local real estate, which has also come under pressure since the deposits piled up. The exposure to disruptive/crypto is likely far higher here than in other banks.

-

Rate risk. The chase for yield was alive and well as the money was flooding into banks. This seems like a good time to bring back “5 Circles of Bond Investor Hell.” There are only a few things you can do when you need yield, one of which is to increase duration, which was apparently done here. Hoping the market cheapens would have worked great, but it rarely does and there is immense pressure not to sit on cash, so I’d be shocked if many had the fortitude to do that. It seems like SIVB may have extended duration. Taking more risk than normal is probably somewhat common across banks, though I’m not sure rate risk would have been the preferred method. I lean towards giving up liquidity (most don’t use it) or increasing structure (my theory on AAA CLOs being more difficult to bust than getting a perfect March Madness bracket).

-

5 Circles of Bond Investor Hell

I see the situation as unique because:

-

They had exceptional growth in a compressed timeframe.

-

Growth occurred during an exceptional dearth of yield.

-

Some of their decisions and the nature of their customer base (to whom they lent) may have set them up with a portfolio that was more exposed than others.

-

Customers started withdrawing because they needed the money (nothing to do with anything SIVB was doing).

-

Those withdrawals triggered selling, which turned positions meant for accrual accounting into realized losses! That combination following a period of explosive growth seemed to be what caught the attention of people.

-

Now something that looks more like a “normal” run starts. Losses get exposed. The balance sheet faces more scrutiny. Some clients may get nervous. The cash burn, which started after March 2022, likely continued into Q1 2023 (the last data point was at the end of 2022). This is where we are now and is why everyone is worried about other banks!

I am stuck seeing this as far more unique than systemic, hence the recent selling is overdone!

Some Bad News for All Banks

The banking sector, even if I’m correct, will not get off scot-free.

-

Interest rates on deposits will probably have to get “competitive” more rapidly than they normally would. People covered by the FDIC limits will care less as there is no credit risk to the institution, but recent focus on higher yields across the board will make many consider keeping enough “working capital” at the bank, while owning money market funds or other higher yielding assets (including Certificates of Deposit at many banks). Personally I think that should be SOP and is how I think about my deposits – and no, I’m not trying to get banks to hate me! Those above the FDIC limits are exposed as senior unsecured creditors if a bank fails. The returns paid to senior unsecured creditors are much better than those paid on deposits, but the services provided by banks (anything from LOCs to simple check cashing and enabling payroll and business activities to function seamlessly) have immense value. I could see some banks increasing their payment rates on deposits which would eat into NIM, but that would be a valuation issue, not a credit issue. Bank P/E multiples being too high already don’t keep me up at night. I suspect little of the NIM gets a great multiple in any case, as investors have been expecting banks to slowly raise the amount they pay on deposits.

-

Closer scrutiny to bank portfolios. People far smarter than me (with better tools at their fingertips) are looking at what exposures banks have on their books. Making that analysis more complex will be the fact that many of the exposures (and certainly all of the hedges) will be in derivative books that I think are opaque at best. I would not want to be in charge of a bank that faces the headline “XYZ loaded up on duration during ZIRP” in the coming days. That is the sort of headline that can trigger people taking out deposits. If I believed a lot of banks really extended duration during ZIRP, I would be scared to death right now about recommending banks, but:

-

Asset growth was not that far above normal for most banks.

-

Private debt, credit risk, and structured risk all seem more natural for banks, all of which have been weathering this market better than sovereign debt (assuming the rate risk is taken out, which it should be in my vision of bank risk management).

-

I am fully aware of these two risks, but think that:

-

Most banks are well prepared to deal with both issues and will not face any sort of a run. I am saying this, fully knowing how that “bank run” sentiment can spread like wildfire. You cannot believe how nervous I’ve been writing this report (which is maybe why it is longer than usual) because I do understand how afraid people are and how quickly even a false allegation can trigger negative momentum.

-

Valuations (after the recent shellacking) offer upside in a tricky market environment – both on the equity and credit side of the equation.

The Non-FDIC Insured Depositors

I saw a stat that SIVB has only about 3% of its deposits fully covered by the FDIC (very low compared to most banks). Presumably this is a bank for rich individuals and corporations.

This is the group that is in limbo and I don’t fully understand the next steps.

If you have $100,000,000 on deposit to meet your obligations, how much of that can you access?

In theory, as I understand this:

-

The assets of the bank are worth X.

-

The FDIC depositors (and maybe some other senior stuff) are worth Y.

-

Z is the amount of deposits above the FDIC limits and other senior unsecured debt.

-

If X – Y > Z then there is equity value. I’m not sure I’d write that off yet, but that is just me musing about the subject. I don’t have an opinion and am not basing my overall bank recommendation on it, but it seems to have been left for dead rather quickly (even by panic standards).

-

If X – Y < Z then Z will be impaired and not receive 100 cents on the dollar.

-

Lehman claims, which were classified as unsecured debt because they filed before investment banks became banks under emergency GFC policy, settled at about 20% of par (though they ultimately recovered 100% plus accrued). It isn’t completely irrelevant (it wasn’t a bank), but it also gives us the sense of how complex this can be with financial instruments.

-

Some things in favor of SIVB’s valuations:

-

It seems that much of their portfolio is liquid, making it easier to monetize and start establishing minimal values (and presumably immediate availability) for the unsecured creditors.

-

Their customer base is still a who’s who of the valley and disruptive space and many other banks and financial service companies will want to establish relationships which will help the valuation and/or any necessary sale of these assets.

-

So far it is isolated. If their situation is unique (as I obviously believe it is) then the market has a large, but digestible set of assets to absorb. If this is just the tip of the iceberg, then we are in some serious trouble as there will be more forced selling and huge pools of fixed income “in for the bid”. During the GFC, almost every bank owned too much of the same thing and needed to sell. Remember AIG FP and their super senior protection on corporate credit? That part of their portfolio never sniffed a loss as corporate credit failure was extremely well contained even in the GFC (however, the mortgage super senior was a mess). Overall, recovery rates tend to be higher during good economic times because there are fewer distressed sellers. So far this is a unique case, and that helps maximize value.

Understanding how much access to above FDIC limit deposits companies (and individuals) will have by Monday is crucial for the disruptive companies – more so than for other banks! Access (to at least a portion) is necessary for many to function. I fully expect there to be some contingencies allowing some % access, though I could be wrong.

White Knight Dream?

I would not be shocked to see a “white knight” investor appear for the entire entity (possibly by Monday) because it makes a lot of the mess regarding the unsecured depositors go away (or at least more manageable).

In the early stages of the financial crisis, we saw various entities get absorbed with a nod (if not a gentle push) from the regulators, when only months before these transactions would have faced regulatory opposition.

The “easiest” and least painful way to value the assets might be via an acquisition by one large institution. I see two hurdles/questions facing that “dream”:

-

Will SIVB accept a valuation or will they want to work their way out, quite possibly, attempting to generate cash for equity holders and not just depositors?

-

Will banks, the natural buyer, be worried about their own deposit base too much to attempt an ambitious purchase, even with a nod from the regulators?

I’m convinced that the Fed learned one massive lesson from the GFC (we saw Europe do a semi-decent job with their own debt crisis) – DON’T LET CONFIDENCE IN THE BANKING SECTOR FAIL!!!!

Nothing else really matters. Financial institutions can write “living wills” until the cows come home, but if we get to that point, all bets are off.

If this is isolated (or even if it isn’t), regulators are supposed to be ring-fencing it in because the last thing they need is for “bank run” to become the word of the week. That is hard to walk back, so getting out in front of it is crucial.

Given how quickly they responded after Covid lockdowns (at warp speed relative to the almost plodding behavior back in 2007 and early 2008), there is hope.

I bet there will be a lot of green dots on Bloomberg terminals on Sunday night – I remember being there when $2 dollars/share came across as the price for Bear Stearns (and physically tapping my screen with my finger, thinking the 2 was a typo).

One thing many forget (or don’t know) about the JPM purchase of Bear was that it was accompanied by an immediate and non-contingent guarantee of Bear’s derivative book. Even if the equity deal didn’t consummate, the derivative book was JPM’s. No one ever really explained how that would work, and there wasn’t much (if any) formal guarantee language.

I Like Mid Banks, I Cannot Lie

I also like big banks and small banks and am more scared of admitting that than I am of singing the original lyrics from this song – so yes, I’ve dragged myself to this hill and am going to stand my ground on it!

I did not have bank failure Sundays on my 2023 bingo card (but it does bring back memories)!

Loading…