(function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v3.0”; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’)); –>

–>

January 17, 2024

A doctrine used once in December 1868 to make sure that former Confederate President Jefferson Davis never held office again has been revived to justify removing former U.S. President Donald Trump’s name from the ballot of the Colorado Republican primary. The doctrine, called self-execution, allows the terms of the 14th Amendment to be applied without action by Congress.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”); } }); }); }

Self-execution is inconsistent with the 14th Amendment’s text, which provides for enforcement by the U.S. Congress. If it were ever applied to cases beyond those of Davis and Trump (and, as this essay argues, it’s seriously doubtful it should apply to Trump), the results would be chaotic.

Trump has appealed on the grounds that the Colorado ruling violates his due process rights. U.S. Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on February 8.

Section 3

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”); } }); }); }

In December 1865, Alexander Stephens, the former Confederate vice president, showed up at the U.S. Congress with several other former Confederates and demanded to be seated. It had been only eight months since Confederate General Robert E. Lee had surrendered at Appomattox. Stephens’s grandstanding prompted Congress to add Section Three to the as-yet-unratified Fourteenth Amendment, the section used by the Colorado Supreme Court to challenge Trump’s ballot status.

Section Three provides that “No person shall” hold U.S. public office who previously took an oath of loyalty to the United States but then “engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same.”

Jefferson Davis

In June 1867, Davis was charged with rebellion, treason, and insurrection at the federal courthouse in Richmond. Ironically, this was the same building that he had used as an office during the war. His case was highly anticipated. It would be the “trial of the century.”

From the government’s point of view, a lot could go wrong. Trying Davis before a jury that included newly freed blacks could provoke a backlash. Were they truly his peers? At the very least, Davis would get a platform to present his views.

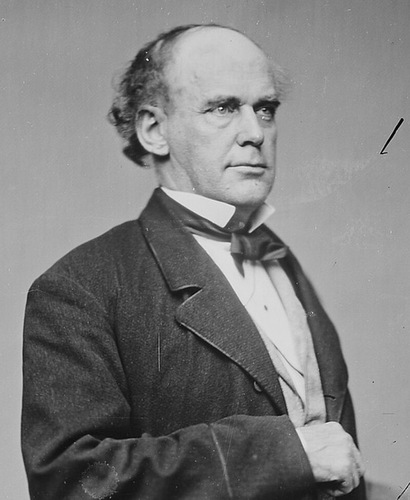

Even if he were convicted, Davis could appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court. Four justices had been appointed by Lincoln, but five had been appointed by earlier pro-slavery presidents. The judges who would ultimately decide the case were Supreme court Chief Justice Salmon Chase and District Judge John Underwood. No one knew how either court might rule. The prosecutors yearned for a solution that would get Davis out of public life.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”); } }); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

The 14th Amendment had been ratified in July, but Congress had not yet passed legislation to enforce it.

The 14th Amendment had been ratified in July, but Congress had not yet passed legislation to enforce it.

Davis moved that the case against him be dismissed. Trying Davis was double jeopardy since he had already been punished by the Fourteenth Amendment, which banned him from federal office, according to the motion. If Section Three applied to Davis and to other former Confederates automatically the moment it was ratified, there was no need for Congress to pass legislation to implement it.

As Chase later put it, the amendment “executed itself.” This novel and intricate argument originated with Chase himself, who had earlier met privately with Davis’s lawyer and advised him to present it.

Underwood dissented from this point of view. Or perhaps he agreed to disagree. On December 3, 1868, the question was referred to the U.S. Supreme Court with no precedent recorded in the court’s syllabus.

On December 25, however, President Andrew Johnson issued a full pardon to former Confederates, including Davis, making the case moot. In February 1869, U.S. Attorney General William Evarts dropped the case.

Griffin’s Case

The first major opinion on the Fourteenth Amendment was Griffin’s Case, decided in May 1869. This time, however, Chief Justice Chase came down the opposite way on the self-execution question. Chase ruled that “proceedings, evidence, decisions, and enforcements of decisions…are indispensable; and these can only be provided for by congress.” Self-execution could justify overriding due process and other civil liberties, something Chase wanted to avoid, according to a 2021 law review article by Gerard Magliocca.

Griffin’s Case concerned the validity of writs issued by judges who were former Confederates. Chase worried that, if these judges were summarily dismissed, there would not be enough judges in the South to process cases. As he explained, self-execution was “a construction which must necessarily occasion great public and private mischief,” and, therefore, must never be preferred to a construction which will occasion neither, or neither in so great degree, unless the terms of the instrument absolutely require such preference.”

In 1871, the North Carolina state legislature selected Zebulon Vance to be U.S. Senator. Vance had been the Confederate governor of North Carolina. This time, the response was more sympathetic. His case spurred the Amnesty Act in 1872, which removed restrictions on former Confederates. Since that time, Section Three has been forgotten—“vestigial,” as Magliocca calls it—until Trump and January 6.

Is the president an officer?

Another question that has been much discussed recently is whether the president is an officer of the United States for purposes of the amendment. According to Article II, the president “shall Commission all the Officers of the United States.” That suggests that the president himself is not an officer.

Magliocca went through the debate that took place in the 1860s. He found that various participants assumed that the offices of president and vice president were covered. No one argued that they weren’t. Although various modern commentators recommend that SCOTUS make use of this loophole (or perhaps drafting error), that would lead to an absurd result.

Colorado’s standardless removal

On December 19, the Colorado court ruled in Anderson v. Griswald that Trump’s name could not be put on the ballot in Colorado, citing the 14th Amendment.

If the Colorado court acted without legal authority, it violated Trump’s right of due process granted under Section 1 of the 14th Amendment: “nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law.” This aspect of the case is what justifies intervention by a federal court.

As for self-execution, it flies against the text of the 14th Amendment: “Congress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.” Whatever the situation in 1868, there is now a statute to enforce the insurrection clause, namely 18 USC § 2383. Trump would have to be convicted of insurrection in federal court for Section Three to apply.

“Congress does not need to pass implementing legislation for Section Three’s disqualification provision to attach, and Section Three is, in that sense, self-executing,” according to the Colorado court. This overlooks both the Griffin Case and the fact that implementation legislation is already on the books.

No one knows what self-execution would mean in practice. If it is legitimate for state courts to rule on this issue, the result would be even more chaotic than anything Chase contemplated. If the U.S. Supreme Court upholds the Colorado decision, it won’t stop with Trump. In his dissent, Colorado Justice Carlos Samour warns against “the potential chaos wrought by an imprudent, unconstitutional, and standardless system in which each state gets to adjudicate Section Three disqualification cases on an ad hoc basis.”

Peter Kauffner is a writer who lives in Vietnam.

Image: Salmon Chase by Matthew Brady.

<!–

–>

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>