Authored by Brian McGlinchey via Stark Realities

America’s latest episode of mass homicide has sparked renewed advocacy for restrictions on gun ownership. Once again, the accompanying debate has many gun control advocates claiming the Second Amendment’s reference to a “well regulated militia” narrows the amendment’s scope if not rendering it altogether moot.

Before we examine those claims, it’s important to ensure readers have a proper general understanding of the Bill of Rights. Contrary to common misperception, these amendments do not bestow privileges upon American citizens. Rather, they are primarily a set of prohibitions against the government infringing on pre-existing human rights all people have.

That’s evident in the language. For example, the First Amendment begins “Congress shall make no law…” This amendment isn’t awarding citizens the rights of religion, speech and assembly — it’s outlawing the government’s thwarting of those innate and universal human rights.

Similarly, the Fourth Amendment asserts that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated.” Again, the authors are not granting those rights, they are protecting them.

When the Bill of Rights was proposed, some feared the enumeration of a handful of rights could be misinterpreted as providing a comprehensive catalogue — and thus empowering the government to infringe on human rights not specified. That’s why they included the Ninth Amendment, asserting that “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

“Amendment II. A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

With that understanding of the Bill of Rights in mind, we see that, via the Second Amendment, the founders explicitly asserted that there is a “right of the people to keep and bear arms.”

What about that reference to “a well regulated militia”? As we set out to scrutinize the phrase, let’s first observe that the Second Amendment contains two distinct components serving two different purposes:

-

An operative clause that sets out a specific prohibition against the government’s infringement on a right: …the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

-

A prefatory clause that announces a purpose: A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State…

Positioned in the prefatory clause, the “well regulated Militia” reference merely serves to provide a rationale — and not necessarily the only rationale — for the operative clause that follows.

While the Second Amendment stands apart from the others in the Bill of Rights by having a prefatory clause, such clauses were common in state constitutions of the era.

Prefatory clauses were used to help “sell” amendments to those being asked to approve them. In this case, the authors were pointing to the necessity of an armed populace as the well from which militias are drawn — militias seen as a vital safeguard against the federal government they were creating.

In particular, America’s founders were wary of the federal government’s potential to create a standing army that could be used to destroy state sovereignty and individual liberties. Seeking to “sell” the amendment to drafting committees and state ratifying conventions, it made sense for the authors to highlight the link between militias and the people’s right to bear arms.

Given their purpose — that is, to cite one or more of many possible rationales — prefatory clauses don’t rightly constrain operative clauses, particularly one as explicit as the Second Amendment’s, which pointedly recognizes a “right of the people to keep and bear arms.”

Even if the prefatory clause did have any teeth, those seeking to interpret it as tightly restricting the gun-eligible population run into yet another wall, in that militias are assembled from the citizenry at large.

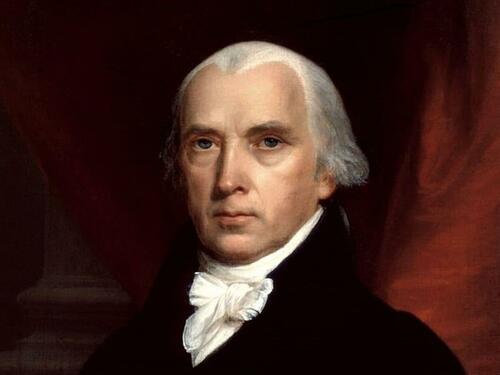

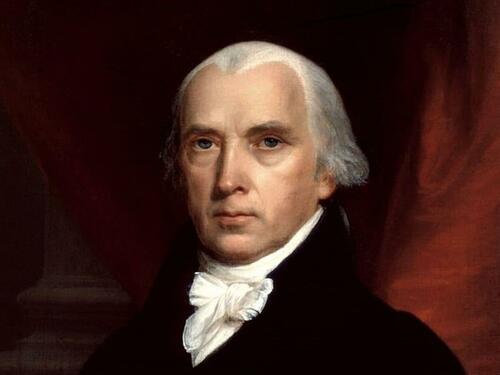

Indeed, one revision of James Madison's draft of the Second Amendment drove home this point. It began, “A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people…”

Listen to Pennsylvanian Tench Coxe, as he championed the Constitution’s ratification: “The powers of the sword are in the hands of the yeomanry of America from sixteen to sixty.” Summarizing the Second Amendment, Coxe said, “The people are confirmed by the article in their right to keep and bear their private arms.”

Multiple state constitutional provisions of the era, some of which predate the Bill of Rights, offer additional confirmation that the armed right of self-defense belongs to individuals. As one representative example, consider the language of Vermont’s 1777 Constitution: “The right of the citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State shall not be questioned.”

Further disregarding the Second Amendment’s explicit enumeration of “the right of the people to bear arms,” some claim the existence of the National Guard renders the Second Amendment entirely moot, since, via the Guard, each state has a “militia” with its own arsenal of arms.

In the US, you do NOT have a constitutional right to own a gun UNLESS you are in a well-regulated militia.

— Student Loans Suck 🟥 (@Seracohw6) March 27, 2023

The well-regulated militia is the National Guard.

That is, literally, what the 2nd amendment says.

Recall, however, that the founders viewed militias as a check on the federal government’s power, with fear that the federal government might create a standing army with the potential to tyrannize the states and the people.

Thanks to the National Defense Act of 1916 and amendments in 1933, today’s National Guard is legally a part of the United States Army, with state governments exercising only limited government control. Enlistment oaths have evolved to reflect that, with National Guard soldiers promising to obey the orders of both the president of the United States and the governor.

The Guard’s military training and the selection of its officers are controlled by the federal government. Troops are subject to activation pursuant to any number of federal missions, including — as we’ve seen too often — overseas combat deployments that render them useless to the states where their citizen-soldiers live.

Clearly, under such federal control, the National Guard cannot be seen as a counterbalance against federal power, and thus does not fulfill the Second Amendment’s aspiration to enable “well-regulated militias…necessary to the security of a free state.”

Finally, no tour of the Second Amendment’s language would be complete without addressing “well regulated” as it’s applied to “militia.” Today, people often and understandably assume that descriptor refers to regulation in the modern sense of external government control. However, in the late 1700s, “well regulated” simply meant orderly, trained and disciplined — qualities that militias should aspire to.

To summarize:

-

The Second Amendment explicitly recognizes the existence of “a right of the people” — not just those currently in militias — “to keep and bear arms.”

-

Placed in a prefatory clause, the “militia” reference merely announces one rationale for the Second Amendment. Regardless of how “militia” is interpreted, its presence does not constrain the operative-clause prohibition of government infringement against the right of the people to keep and bears arms.

-

Today’s National Guard is part of the U.S. Army and under heavy federal control. It cannot be used by the peoples of the separate states as a counterbalance to the federal government’s standing army — and thus is not a “militia” in the sense the term is used in the Second Amendment.

Stark Realities undermines official narratives, demolishes conventional wisdom and exposes fundamental myths across the political spectrum. Read more and subscribe at starkrealities.substack.com

Authored by Brian McGlinchey via Stark Realities

America’s latest episode of mass homicide has sparked renewed advocacy for restrictions on gun ownership. Once again, the accompanying debate has many gun control advocates claiming the Second Amendment’s reference to a “well regulated militia” narrows the amendment’s scope if not rendering it altogether moot.

Before we examine those claims, it’s important to ensure readers have a proper general understanding of the Bill of Rights. Contrary to common misperception, these amendments do not bestow privileges upon American citizens. Rather, they are primarily a set of prohibitions against the government infringing on pre-existing human rights all people have.

That’s evident in the language. For example, the First Amendment begins “Congress shall make no law…” This amendment isn’t awarding citizens the rights of religion, speech and assembly — it’s outlawing the government’s thwarting of those innate and universal human rights.

Similarly, the Fourth Amendment asserts that “the right of the people to be secure in their persons, houses, papers, and effects, against unreasonable searches and seizures, shall not be violated.” Again, the authors are not granting those rights, they are protecting them.

When the Bill of Rights was proposed, some feared the enumeration of a handful of rights could be misinterpreted as providing a comprehensive catalogue — and thus empowering the government to infringe on human rights not specified. That’s why they included the Ninth Amendment, asserting that “the enumeration in the Constitution, of certain rights, shall not be construed to deny or disparage others retained by the people.”

“Amendment II. A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State, the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.”

With that understanding of the Bill of Rights in mind, we see that, via the Second Amendment, the founders explicitly asserted that there is a “right of the people to keep and bear arms.”

What about that reference to “a well regulated militia”? As we set out to scrutinize the phrase, let’s first observe that the Second Amendment contains two distinct components serving two different purposes:

-

An operative clause that sets out a specific prohibition against the government’s infringement on a right: …the right of the people to keep and bear Arms, shall not be infringed.

-

A prefatory clause that announces a purpose: A well regulated Militia, being necessary to the security of a free State…

Positioned in the prefatory clause, the “well regulated Militia” reference merely serves to provide a rationale — and not necessarily the only rationale — for the operative clause that follows.

While the Second Amendment stands apart from the others in the Bill of Rights by having a prefatory clause, such clauses were common in state constitutions of the era.

Prefatory clauses were used to help “sell” amendments to those being asked to approve them. In this case, the authors were pointing to the necessity of an armed populace as the well from which militias are drawn — militias seen as a vital safeguard against the federal government they were creating.

In particular, America’s founders were wary of the federal government’s potential to create a standing army that could be used to destroy state sovereignty and individual liberties. Seeking to “sell” the amendment to drafting committees and state ratifying conventions, it made sense for the authors to highlight the link between militias and the people’s right to bear arms.

Given their purpose — that is, to cite one or more of many possible rationales — prefatory clauses don’t rightly constrain operative clauses, particularly one as explicit as the Second Amendment’s, which pointedly recognizes a “right of the people to keep and bear arms.”

Even if the prefatory clause did have any teeth, those seeking to interpret it as tightly restricting the gun-eligible population run into yet another wall, in that militias are assembled from the citizenry at large.

Indeed, one revision of James Madison’s draft of the Second Amendment drove home this point. It began, “A well regulated militia, composed of the body of the people…”

Listen to Pennsylvanian Tench Coxe, as he championed the Constitution’s ratification: “The powers of the sword are in the hands of the yeomanry of America from sixteen to sixty.” Summarizing the Second Amendment, Coxe said, “The people are confirmed by the article in their right to keep and bear their private arms.”

Multiple state constitutional provisions of the era, some of which predate the Bill of Rights, offer additional confirmation that the armed right of self-defense belongs to individuals. As one representative example, consider the language of Vermont’s 1777 Constitution: “The right of the citizens to bear arms in defense of themselves and the State shall not be questioned.”

Further disregarding the Second Amendment’s explicit enumeration of “the right of the people to bear arms,” some claim the existence of the National Guard renders the Second Amendment entirely moot, since, via the Guard, each state has a “militia” with its own arsenal of arms.

In the US, you do NOT have a constitutional right to own a gun UNLESS you are in a well-regulated militia.

The well-regulated militia is the National Guard.

That is, literally, what the 2nd amendment says.

— Student Loans Suck 🟥 (@Seracohw6) March 27, 2023

Recall, however, that the founders viewed militias as a check on the federal government’s power, with fear that the federal government might create a standing army with the potential to tyrannize the states and the people.

Thanks to the National Defense Act of 1916 and amendments in 1933, today’s National Guard is legally a part of the United States Army, with state governments exercising only limited government control. Enlistment oaths have evolved to reflect that, with National Guard soldiers promising to obey the orders of both the president of the United States and the governor.

The Guard’s military training and the selection of its officers are controlled by the federal government. Troops are subject to activation pursuant to any number of federal missions, including — as we’ve seen too often — overseas combat deployments that render them useless to the states where their citizen-soldiers live.

Clearly, under such federal control, the National Guard cannot be seen as a counterbalance against federal power, and thus does not fulfill the Second Amendment’s aspiration to enable “well-regulated militias…necessary to the security of a free state.”

Finally, no tour of the Second Amendment’s language would be complete without addressing “well regulated” as it’s applied to “militia.” Today, people often and understandably assume that descriptor refers to regulation in the modern sense of external government control. However, in the late 1700s, “well regulated” simply meant orderly, trained and disciplined — qualities that militias should aspire to.

To summarize:

-

The Second Amendment explicitly recognizes the existence of “a right of the people” — not just those currently in militias — “to keep and bear arms.”

-

Placed in a prefatory clause, the “militia” reference merely announces one rationale for the Second Amendment. Regardless of how “militia” is interpreted, its presence does not constrain the operative-clause prohibition of government infringement against the right of the people to keep and bears arms.

-

Today’s National Guard is part of the U.S. Army and under heavy federal control. It cannot be used by the peoples of the separate states as a counterbalance to the federal government’s standing army — and thus is not a “militia” in the sense the term is used in the Second Amendment.

Stark Realities undermines official narratives, demolishes conventional wisdom and exposes fundamental myths across the political spectrum. Read more and subscribe at starkrealities.substack.com

Loading…