Authored by Sam Dorman via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

A slew of lawsuits are seeking to disqualify President Donald Trump from running for office in 2024, creating an increasingly unstable presidential election season.

All of these attempts rest on an argument that the "insurrection" clause of the 14th Amendment bars the former president from appearing on the ballot.

The most significant decision was handed down on Dec. 21, when the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in a 4–3 decision that President Trump couldn’t appear on the state’s ballot because he had engaged in an insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021.

The Colorado ruling appears to be triggering and renewing efforts to kick the former president off the ballot in other blue-leaning states, including New York, California, and Pennsylvania.

A lower court in Colorado had similarly ruled that President Trump engaged in an insurrection but stopped short of disqualifying him after finding that the 14th Amendment doesn't apply to presidents.

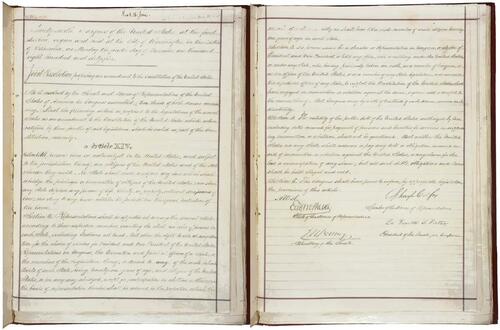

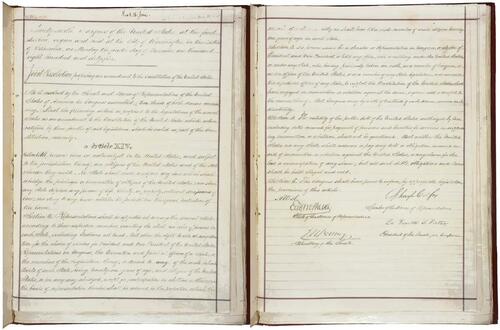

Enacted after the Civil War, the text of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment reads: “No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.”

This relatively untested provision is now set to come before the nation's highest court.

"This case is surely destined for the Supreme Court to interpret the 14th Amendment and resolve whether Trump is disqualified from the presidency," said University of Michigan law professor Barbara McQuade, who left the Trump administration among a wave of resignations at the beginning of his term.

Who that section applies to, what constitutes an insurrection, and how the section is enforced have been the subject of vigorous debate.

Embedded within those questions are a series of others that could make deciding or enforcing ballot disqualification cases especially complicated.

Here are some of the major questions that courts and politicians may consider.

1. What Is an Insurrection?

Efforts to disqualify President Trump hinge partly on whether his actions surrounding the Jan. 6, 2021, riots qualify as engaging in the type of insurrection mentioned in Section 3.

To answer that question, observers have drawn from historical records, federal law, and evidence surrounding Jan. 6.

According to Colorado District Judge Sarah Wallace’s reasoning, President Trump used language he knew would provoke violence on Jan. 6, 2021, but was vague enough to maintain plausible deniability. For her, that satisfied Section 3’s requirement that an individual “engaged in insurrection or rebellion.”

Some, however, have questioned that line of reasoning given that none of the Jan. 6 defendants, nor President Trump himself, have been charged with violating federal law regarding an insurrection.

South Texas College law professor Josh Blackman has said that “federal prosecutions for insurrection are extremely rare” and told Click2Houston that crimes such as "insurrection, treason, or sedition are very, very hard to prove.”

“ They require basically an intent to try to frustrate or subvert the government,” he said.

There are additional questions as to whether the 14th Amendment defines insurrection the same way federal law does, or whether federal law and the 14th Amendment require the same level of proof to establish that individuals are guilty of insurrection.

Under the 14th Amendment, meeting the threshold of "insurrection" is "an extraordinarily high bar," said Roger Severino, vice president of domestic policy at The Heritage Foundation. He also served in the Health and Human Services Department under President Trump.

“I didn't see anything sufficient to justify such an incendiary charge,” Mr. Severino told The Epoch Times.

He said the reference to insurrection in the 14th Amendment came about after invasions of the north during the Civil War.

During the Civil War, “you had armed invasions of the north ... that's what insurrection was referring to in the 14th Amendment,” he said.

Horace Cooper, senior fellow with the National Center for Public Policy Research, who formerly taught constitutional law at George Mason University, said that “their target was specifically the Confederacy."

"Their target was not anyone who supported the French in the French–Indian War. Their target was not anyone who supported the British in the British–American War. Even though the language isn’t written in a way to limit those, the rationale was the Confederacy,” he said.

Still, some scholars say that President Trump has satisfied the 14th Amendment's requirements for engaging in an insurrection.

"Section Three covers a broad range of conduct against the authority of the constitutional order, including many instances of indirect participation or support as 'aid or comfort,'" said University of Chicago law professor William Baude and University of St. Thomas law professor Michael Stokes Paulsen in a paper.

"It covers a broad range of former offices, including the presidency. And in particular, it disqualifies former President Donald Trump, and potentially many others, because of their participation in the attempted overthrow of the 2020 presidential election."

2. Is Trump an 'Officer of the United States'?

Judge Wallace’s opinion refrained from disqualifying President Trump because, she said, even if he committed an insurrection, she didn’t have enough evidence to definitively say he was the type of “officer” that the 14th Amendment prohibits from engaging in an insurrection.

Hans von Spakovsky, a former member of the Federal Election Commission, has argued that two prior Supreme Court decisions contain language indicating that “officers” of the United States don't include presidents.

More specifically, both Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board and United States v. Mouat define officers as appointees of the president and others.

Washington University law professor Andrea Katz disagrees.

“You can find cases that have held certainly to the contrary,” she told The Epoch Times, pointing to Lucia v. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Quoting a prior court decision, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan said in 2018 that an officer “must occupy a ‘continuing’ position established by law, and must ‘exercis[e] significant authority pursuant to the laws of the United States.’”

Ms. Katz said that “it seems like both common understanding—the text of the Supreme Court, and the legislators’ understanding in drafting the 14th amendment—was that the president was going to be covered by this language.”

3. Can Courts Enforce Section 3?

Even if it was clear that Section 3 included President Trump’s conduct, questions remain as to whether courts can remove him from the ballot.The answer to those questions could depend on how much authority state laws grant their secretaries of state. It could also depend on how Congress describes the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

Read more here...

Authored by Sam Dorman via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

A slew of lawsuits are seeking to disqualify President Donald Trump from running for office in 2024, creating an increasingly unstable presidential election season.

All of these attempts rest on an argument that the “insurrection” clause of the 14th Amendment bars the former president from appearing on the ballot.

The most significant decision was handed down on Dec. 21, when the Colorado Supreme Court ruled in a 4–3 decision that President Trump couldn’t appear on the state’s ballot because he had engaged in an insurrection on Jan. 6, 2021.

The Colorado ruling appears to be triggering and renewing efforts to kick the former president off the ballot in other blue-leaning states, including New York, California, and Pennsylvania.

A lower court in Colorado had similarly ruled that President Trump engaged in an insurrection but stopped short of disqualifying him after finding that the 14th Amendment doesn’t apply to presidents.

Enacted after the Civil War, the text of Section 3 of the 14th Amendment reads: “No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice-President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.”

This relatively untested provision is now set to come before the nation’s highest court.

“This case is surely destined for the Supreme Court to interpret the 14th Amendment and resolve whether Trump is disqualified from the presidency,” said University of Michigan law professor Barbara McQuade, who left the Trump administration among a wave of resignations at the beginning of his term.

Who that section applies to, what constitutes an insurrection, and how the section is enforced have been the subject of vigorous debate.

Embedded within those questions are a series of others that could make deciding or enforcing ballot disqualification cases especially complicated.

Here are some of the major questions that courts and politicians may consider.

1. What Is an Insurrection?

Efforts to disqualify President Trump hinge partly on whether his actions surrounding the Jan. 6, 2021, riots qualify as engaging in the type of insurrection mentioned in Section 3.

To answer that question, observers have drawn from historical records, federal law, and evidence surrounding Jan. 6.

According to Colorado District Judge Sarah Wallace’s reasoning, President Trump used language he knew would provoke violence on Jan. 6, 2021, but was vague enough to maintain plausible deniability. For her, that satisfied Section 3’s requirement that an individual “engaged in insurrection or rebellion.”

Some, however, have questioned that line of reasoning given that none of the Jan. 6 defendants, nor President Trump himself, have been charged with violating federal law regarding an insurrection.

South Texas College law professor Josh Blackman has said that “federal prosecutions for insurrection are extremely rare” and told Click2Houston that crimes such as “insurrection, treason, or sedition are very, very hard to prove.”

“They require basically an intent to try to frustrate or subvert the government,” he said.

There are additional questions as to whether the 14th Amendment defines insurrection the same way federal law does, or whether federal law and the 14th Amendment require the same level of proof to establish that individuals are guilty of insurrection.

Under the 14th Amendment, meeting the threshold of “insurrection” is “an extraordinarily high bar,” said Roger Severino, vice president of domestic policy at The Heritage Foundation. He also served in the Health and Human Services Department under President Trump.

“I didn’t see anything sufficient to justify such an incendiary charge,” Mr. Severino told The Epoch Times.

He said the reference to insurrection in the 14th Amendment came about after invasions of the north during the Civil War.

During the Civil War, “you had armed invasions of the north … that’s what insurrection was referring to in the 14th Amendment,” he said.

Horace Cooper, senior fellow with the National Center for Public Policy Research, who formerly taught constitutional law at George Mason University, said that “their target was specifically the Confederacy.”

“Their target was not anyone who supported the French in the French–Indian War. Their target was not anyone who supported the British in the British–American War. Even though the language isn’t written in a way to limit those, the rationale was the Confederacy,” he said.

Still, some scholars say that President Trump has satisfied the 14th Amendment’s requirements for engaging in an insurrection.

“Section Three covers a broad range of conduct against the authority of the constitutional order, including many instances of indirect participation or support as ‘aid or comfort,’” said University of Chicago law professor William Baude and University of St. Thomas law professor Michael Stokes Paulsen in a paper.

“It covers a broad range of former offices, including the presidency. And in particular, it disqualifies former President Donald Trump, and potentially many others, because of their participation in the attempted overthrow of the 2020 presidential election.”

2. Is Trump an ‘Officer of the United States’?

Judge Wallace’s opinion refrained from disqualifying President Trump because, she said, even if he committed an insurrection, she didn’t have enough evidence to definitively say he was the type of “officer” that the 14th Amendment prohibits from engaging in an insurrection.

Hans von Spakovsky, a former member of the Federal Election Commission, has argued that two prior Supreme Court decisions contain language indicating that “officers” of the United States don’t include presidents.

More specifically, both Free Enterprise Fund v. Public Company Accounting Oversight Board and United States v. Mouat define officers as appointees of the president and others.

Washington University law professor Andrea Katz disagrees.

“You can find cases that have held certainly to the contrary,” she told The Epoch Times, pointing to Lucia v. Securities and Exchange Commission.

Quoting a prior court decision, Supreme Court Justice Elena Kagan said in 2018 that an officer “must occupy a ‘continuing’ position established by law, and must ‘exercis[e] significant authority pursuant to the laws of the United States.’”

Ms. Katz said that “it seems like both common understanding—the text of the Supreme Court, and the legislators’ understanding in drafting the 14th amendment—was that the president was going to be covered by this language.”

In its decision, the Colorado Supreme Court argued that the amendment’s drafters “understood the president as an officer of the United States” and that the Constitution as a whole supported that conclusion.

3. Can Courts Enforce Section 3?

Even if it was clear that Section 3 included President Trump’s conduct, questions remain as to whether courts can remove him from the ballot.

The answer to those questions could depend on how much authority state laws grant their secretaries of state. It could also depend on how Congress describes the events of Jan. 6, 2021.

Read more here…

Loading…