Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

A full guarantee of all bank deposits would spell the end of moral hazard and mark the final chapter of the dollar’s multi-decade debasement.

It’s said the cover-up is worse than the crime. With the latest banking crisis in the US, it’s the clean-up that could end up doing far more lasting damage. The failure of SVB et al prompted the FDIC to guarantee that all depositors will be made whole, whether insured or not.

The precedent is being set, with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen commenting on Tuesday that the US could repeat its actions if other banks became imperiled. She was referring to smaller lenders, and denied the next day that insurance would be “blanket”, but given the regulatory direction of travel over the last forty years, this will inevitability apply to any lender when push comes to shove.

This marks the end of moral hazard and, ultimately, the final desecration of the Fed’s balance sheet.

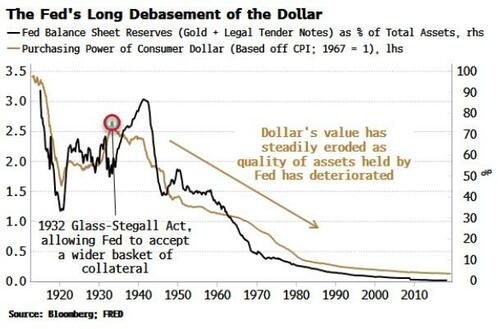

The dollar is a liability of the central bank; therefore, this would mean further erosion of its real value, compounding the decimation of its purchasing power seen over the last century.

The 1932 Glass-Stegall Act was the beginning of the end, allowing the Fed to accept a wider basket of collateral it could lend against: riskier assets such as longer-term Treasury securities. The falling quality of collateral has continued, with the Fed lending against corporate debt in recent years.

The end result is the Fed’s balance sheet has steadily deteriorated, and with it the real value of the dollar.

A de facto expansion of insurance to all deposits will lead to a further erosion in the Fed’s balance sheet. Why? Firstly, note that deposit-insurance schemes typically lead to less, not more, bank stability.

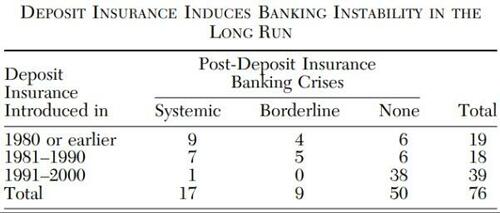

Several studies have shown that countries with deposit-insurance schemes tend to see more bank failures. The more generous the scheme, the greater the instability.

Source: Columbia University

Moral hazard instills discipline in depositors as they pay attention to the bank’s credit risk (something many depositors in SVB signally failed to do.) It also imposes discipline on banks, incentivizing them to structure their cash flows so that they match through all time, thus mitigating the risk of bank runs (cue SVB again).

Why, then, would greater banking instability lead to a further deterioration in the Fed’s balance sheet? It comes down to how US banking has evolved over the last century.

Banks must manage cash flows from assets and liabilities, and their preference is to minimize their cash position each night in order to maximize the productive use of their capital. There is always a “position making” instrument, a liquid asset that banks can use to park excess cash or make up for shortfalls each day.

In the early days of the Federal Reserve system it was commercial loans and USTs; now it is principally the repo market. A bank can “make position” if it can repo in or repo out securities for funds. But if the market for that collateral freezes up, they’re dead.

This is where the Fed steps in - but as the “dealer of last resort” rather than the lender of last resort.

To ensure market liquidity, the Fed must underwrite funding liquidity. And to do that it must be willing to accept as collateral whatever the banking sector’s position-making instruments are. If it doesn’t, the game’s up.

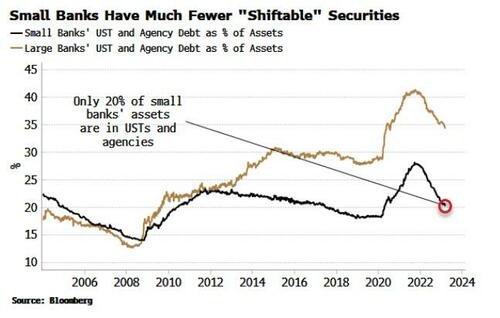

SVB happened to have a high proportion of USTs and mortgage-backed securities on its balance sheet, making the Fed’s life easy in creating the BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program), which accepts government and government-backed collateral. But this does not get to the heart of the problem. Only a fifth of small banks’ assets are currently shiftable on to the Fed’s balance - less than for larger lenders — leaving them considerably exposed.

Deposit insurance only mitigates banks’ vulnerability to bank runs; it does not insulate them from liquidity or insolvency risk. SVB et al are very likely not the only fragile US banks, and as the economy slows, asset prices fall and delinquencies and bankruptcies rise, we are likely to see more banks needing support.

The logical outcome is that the Fed will have to increasingly accept poorer quality collateral — especially from smaller banks, with their large exposure to residential and commercial real estate. We have been here before, when during the pandemic the Fed began to accept the corporate debt of even junk-rated companies.

Minsky himself stressed the centrality of banking to financial stability, noting that imprudent banks (read: operating without moral hazard) are more likely to finance unproductive projects, which then leads to inflation.

So there we have it. Inflation and a further debasement of the Fed’s balance sheet.

With an abnegation of moral hazard, the long-term value of the dollar doesn’t stand a chance.

Authored by Simon White, Bloomberg macro strategist,

A full guarantee of all bank deposits would spell the end of moral hazard and mark the final chapter of the dollar’s multi-decade debasement.

It’s said the cover-up is worse than the crime. With the latest banking crisis in the US, it’s the clean-up that could end up doing far more lasting damage. The failure of SVB et al prompted the FDIC to guarantee that all depositors will be made whole, whether insured or not.

The precedent is being set, with Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen commenting on Tuesday that the US could repeat its actions if other banks became imperiled. She was referring to smaller lenders, and denied the next day that insurance would be “blanket”, but given the regulatory direction of travel over the last forty years, this will inevitability apply to any lender when push comes to shove.

This marks the end of moral hazard and, ultimately, the final desecration of the Fed’s balance sheet.

The dollar is a liability of the central bank; therefore, this would mean further erosion of its real value, compounding the decimation of its purchasing power seen over the last century.

The 1932 Glass-Stegall Act was the beginning of the end, allowing the Fed to accept a wider basket of collateral it could lend against: riskier assets such as longer-term Treasury securities. The falling quality of collateral has continued, with the Fed lending against corporate debt in recent years.

The end result is the Fed’s balance sheet has steadily deteriorated, and with it the real value of the dollar.

A de facto expansion of insurance to all deposits will lead to a further erosion in the Fed’s balance sheet. Why? Firstly, note that deposit-insurance schemes typically lead to less, not more, bank stability.

Several studies have shown that countries with deposit-insurance schemes tend to see more bank failures. The more generous the scheme, the greater the instability.

Source: Columbia University

Moral hazard instills discipline in depositors as they pay attention to the bank’s credit risk (something many depositors in SVB signally failed to do.) It also imposes discipline on banks, incentivizing them to structure their cash flows so that they match through all time, thus mitigating the risk of bank runs (cue SVB again).

Why, then, would greater banking instability lead to a further deterioration in the Fed’s balance sheet? It comes down to how US banking has evolved over the last century.

Banks must manage cash flows from assets and liabilities, and their preference is to minimize their cash position each night in order to maximize the productive use of their capital. There is always a “position making” instrument, a liquid asset that banks can use to park excess cash or make up for shortfalls each day.

In the early days of the Federal Reserve system it was commercial loans and USTs; now it is principally the repo market. A bank can “make position” if it can repo in or repo out securities for funds. But if the market for that collateral freezes up, they’re dead.

This is where the Fed steps in – but as the “dealer of last resort” rather than the lender of last resort.

To ensure market liquidity, the Fed must underwrite funding liquidity. And to do that it must be willing to accept as collateral whatever the banking sector’s position-making instruments are. If it doesn’t, the game’s up.

SVB happened to have a high proportion of USTs and mortgage-backed securities on its balance sheet, making the Fed’s life easy in creating the BTFP (Bank Term Funding Program), which accepts government and government-backed collateral. But this does not get to the heart of the problem. Only a fifth of small banks’ assets are currently shiftable on to the Fed’s balance – less than for larger lenders — leaving them considerably exposed.

Deposit insurance only mitigates banks’ vulnerability to bank runs; it does not insulate them from liquidity or insolvency risk. SVB et al are very likely not the only fragile US banks, and as the economy slows, asset prices fall and delinquencies and bankruptcies rise, we are likely to see more banks needing support.

The logical outcome is that the Fed will have to increasingly accept poorer quality collateral — especially from smaller banks, with their large exposure to residential and commercial real estate. We have been here before, when during the pandemic the Fed began to accept the corporate debt of even junk-rated companies.

Minsky himself stressed the centrality of banking to financial stability, noting that imprudent banks (read: operating without moral hazard) are more likely to finance unproductive projects, which then leads to inflation.

So there we have it. Inflation and a further debasement of the Fed’s balance sheet.

With an abnegation of moral hazard, the long-term value of the dollar doesn’t stand a chance.

Loading…