In the fight against inflation, is it the Fed or the Treasury that calls the shots? The answer is, it’s both.

The Fed raises interest rates to make loans less attractive and bring inflation down, but The Treasury has its own set of magic tricks to artificially “stimulate” or “tighten” the economy as well.

One of them is a Treasury buyback program, something that was just reincarnated for the first time in about two decades. This is where the Treasury repurchases its own outstanding securities from the open market to increase liquidity, stoke, demand, and bring down yields.

If Treasury markets can’t be reigned in, the Fed expands its balance sheet by buying those Treasury securities to add liquidity and stability. These “open market operations” are usually the “money printing” that people are talking about happening at the Fed. “QE” refers more specifically to operations where the Fed is buying other assets beyond just Treasury securities, as occurred in the 2008 crisis and during COVID. But the Treasury buying back its own issued debt is, in essence, QE by another name.

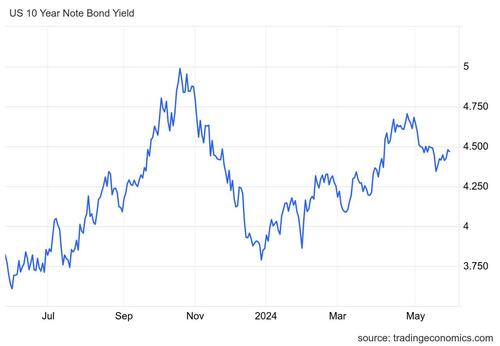

When interpreting Treasury yield data, remember that this market is being heavily manipulated by Yellen - she's conducting the Treasury versions of both Operation Twist and QE, w/ overreliance on short-term issuance and now buybacks; term premium is now virtually nonsensical: pic.twitter.com/RH8UixQOMK

— E.J. Antoni, Ph.D. (@RealEJAntoni) May 1, 2024

While this occurs outside the halls of the Federal Reserve itself, Treasury buybacks are merely a different way to print money from nothing. The US is running a deep, sustained fiscal deficit with no true debt ceiling — so the Treasury buys back its own securities by issuing new debt, which it creates out of thin air. With spending far exceeding revenue, higher interest rates plus more debt means that fiscal deficits accelerate. The short-term stimulative effect of this somewhat offsets the Fed’s tightened monetary policy but digs a deeper hole in the longer term.

One method the Treasury uses is to shorten the average duration of securities so that debts mature sooner. That means more short-term debt (like Treasury bills) versus long-term debt (like Treasury bonds). This encourages more capital flows into the banking sector and helps stave off instability. If it fails, the big banks still win: when smaller banks fail, they’re usually just absorbed by bigger ones where the profits are private but the losses are socialized. The “Too Big to Fail” club becomes even bigger and more powerful.

When the Treasury issues more short-term debt, it’s waging war on the Fed’s higher interest rate policy. Both the Treasury and Fed need to keep Treasury yields down, but tightened monetary policy encourages higher yields. If yields get too high, the bond market — and challenged industries like commercial real estate that rely on debt — are screwed. So while the Fed tightens, the Treasury must loosen. Yields have since gone down, but if inflationary pressures and other factors push them back past 5%, both the Fed and Treasury are trapped.

“Higher for longer” policy at the Fed is even more essential for holding back inflation as the Treasury injects liquidity into markets. If the Fed lowers rates now, the results of simultaneously expansionary monetary and fiscal policy will send consumer prices soaring.

So are the Fed and Treasury in opposition, or are they working together, one changing its policy to prevent a disaster caused by the policies of the other? The answer is complex, but the oversimplified version is that the two have locked the economy into a game of musical chairs where, eventually, the music is bound to stop.

The end result of the Treasury’s showdown with the Fed will still be out-of-control inflation. Both artificially contract and expand the money supply, and their policies have both created an inescapable trap. COVID QE is one big unexploded bomb that is sitting in the center of that trap. And even with the Fed holding off on interest rate cuts in the short term, the Treasury’s buybacks are QE by a different name. With too much inflationary pressure and not enough tools to stop it, the end result of all this fiscal and monetary tinkering will be a disaster for the dollar.

In the fight against inflation, is it the Fed or the Treasury that calls the shots? The answer is, it’s both.

The Fed raises interest rates to make loans less attractive and bring inflation down, but The Treasury has its own set of magic tricks to artificially “stimulate” or “tighten” the economy as well.

One of them is a Treasury buyback program, something that was just reincarnated for the first time in about two decades. This is where the Treasury repurchases its own outstanding securities from the open market to increase liquidity, stoke, demand, and bring down yields.

If Treasury markets can’t be reigned in, the Fed expands its balance sheet by buying those Treasury securities to add liquidity and stability. These “open market operations” are usually the “money printing” that people are talking about happening at the Fed. “QE” refers more specifically to operations where the Fed is buying other assets beyond just Treasury securities, as occurred in the 2008 crisis and during COVID. But the Treasury buying back its own issued debt is, in essence, QE by another name.

When interpreting Treasury yield data, remember that this market is being heavily manipulated by Yellen – she’s conducting the Treasury versions of both Operation Twist and QE, w/ overreliance on short-term issuance and now buybacks; term premium is now virtually nonsensical: pic.twitter.com/RH8UixQOMK

— E.J. Antoni, Ph.D. (@RealEJAntoni) May 1, 2024

While this occurs outside the halls of the Federal Reserve itself, Treasury buybacks are merely a different way to print money from nothing. The US is running a deep, sustained fiscal deficit with no true debt ceiling — so the Treasury buys back its own securities by issuing new debt, which it creates out of thin air. With spending far exceeding revenue, higher interest rates plus more debt means that fiscal deficits accelerate. The short-term stimulative effect of this somewhat offsets the Fed’s tightened monetary policy but digs a deeper hole in the longer term.

One method the Treasury uses is to shorten the average duration of securities so that debts mature sooner. That means more short-term debt (like Treasury bills) versus long-term debt (like Treasury bonds). This encourages more capital flows into the banking sector and helps stave off instability. If it fails, the big banks still win: when smaller banks fail, they’re usually just absorbed by bigger ones where the profits are private but the losses are socialized. The “Too Big to Fail” club becomes even bigger and more powerful.

When the Treasury issues more short-term debt, it’s waging war on the Fed’s higher interest rate policy. Both the Treasury and Fed need to keep Treasury yields down, but tightened monetary policy encourages higher yields. If yields get too high, the bond market — and challenged industries like commercial real estate that rely on debt — are screwed. So while the Fed tightens, the Treasury must loosen. Yields have since gone down, but if inflationary pressures and other factors push them back past 5%, both the Fed and Treasury are trapped.

“Higher for longer” policy at the Fed is even more essential for holding back inflation as the Treasury injects liquidity into markets. If the Fed lowers rates now, the results of simultaneously expansionary monetary and fiscal policy will send consumer prices soaring.

So are the Fed and Treasury in opposition, or are they working together, one changing its policy to prevent a disaster caused by the policies of the other? The answer is complex, but the oversimplified version is that the two have locked the economy into a game of musical chairs where, eventually, the music is bound to stop.

The end result of the Treasury’s showdown with the Fed will still be out-of-control inflation. Both artificially contract and expand the money supply, and their policies have both created an inescapable trap. COVID QE is one big unexploded bomb that is sitting in the center of that trap. And even with the Fed holding off on interest rate cuts in the short term, the Treasury’s buybacks are QE by a different name. With too much inflationary pressure and not enough tools to stop it, the end result of all this fiscal and monetary tinkering will be a disaster for the dollar.

Loading…