By Scott Skyrm, Executive Vice President at Curvature Securities

If you can answer two questions correctly, you might have a unique insight into the direction of monetary policy over the next few years.

-

Does the Fed really need to shrink the SOMA portfolio?

-

Was Milton Friedman right? Or at least partially right?

I sit in a unique position in the financial markets. I’ve been in the Repo market for over 30 years, seen the evolution of the Fed, government programs and how they affect the markets. I’ve seen tightening and easing cycles, crises and booms. Through all of the changes, there’s one thing that’s for sure: The Repo market is a window into what’s going on behind the scenes.

There’s a lot of concern about the fed funds rate right now. Keep in mind, the Fed moves this rate up and down. It was too low for a long time and it will eventually be too high. There might be a recession. Hopefully not. These all seem really important to the market right now, but they’re not the real risk. These are events we’ve experienced many times before. They’re a natural part of the financial markets. What’s important is the unknown unknown.

That’s the “wild card.” Right now, the risk lurking in the shadows is Balance Sheet Runoff. The Fed, the markets, the regulators, and even us Repo guys have limited experience with the Fed shrinking the balance sheet. Bottom line: there’s a risk that Balance Sheet Runoff will breaking something. On top of that, no one’s talking about it! [ZH: that's not true, Mark Cabana has been talking about it for a long time]

Balance Sheet Runoff And New Issuance

The Federal Reserve began growing the SOMA portfolio through a series of Quantitative Easing (QE) programs that originally began in November 2008. The most recent program ran from September 2019 to March 2022. The size of the balance sheet peaked at $8.9 trillion in April 2022 and, shortly thereafter, the Fed announced SOMA portfolio Runoff. That is, they would no longer reinvest the principal and interest payments they receive from maturing securities. The Fed was supposed to let $47.5 billion Treasurys and agency MBS mature each month between June and August. Beginning in September, the Fed is supposed to let $95 billion a month Runoff. At this point, there’s no official end to the Runoff, but I expect it will continue until something breaks.

Think about $95 billion of Balance Sheet Runoff each month. That’s a massive amount of Treasury and agency securities entering the market. Now, when you consider net new Treasury issuance, there’s even more Treasury supply on the way. Though I’ve seen a range of estimates, let’s assume the government budget deficit is $1 trillion. That means there’s another $83 billion a month in new securities coming into the market. Combine Balance Sheet Runoff with net new Treasury issuance and we are looking at about $178 billion of securities coming into the market each month. Every month for the foreseeable future; no end in sight. Think of it this way, there will be $1 trillion more government securities in the market by March 2023. Where’s the cash coming from to pay for these securities? I might have the answer.

Original Sin

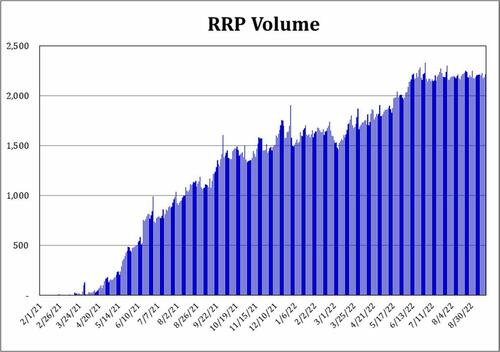

Hopefully, the Fed learned from their mistake. No, not the mistake the equity traders say about the Fed tightening too much. Of course, hindsight is 20/20, but clearly the Fed should have ended QE in 2021. In fact, April 2021 was the date when it should have ended. At that point, as the Fed continued buying, the market was sending the cash right back to the Fed through the RRP facility. Think of it this way: The Fed was injecting liquidity into the financial system and the market didn’t need that cash, so it gave it back to the Fed. Rule of thumb, when RRP volume increases during QE buying, the program is no longer effective

Last Time Around

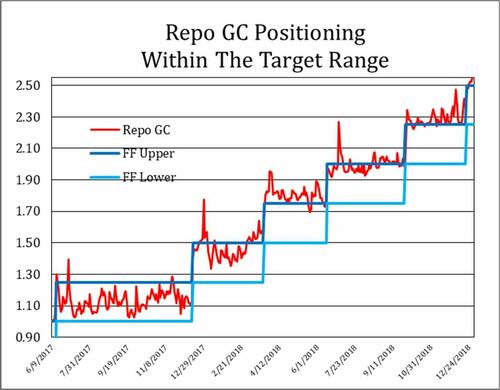

Because QE overstayed its welcome, the Fed now needs to wrestle with an even larger balance sheet. The last time around, Balance Sheet Runoff didn’t quite go so well. During the 2017 to 2019 Runoff period, the Fed shrunk the SOMA portfolio from $4.3 trillion to $3.6 trillion – a total of about $700 billion. From 2017 through 2018, the market absorbed that supply without incident. At least for a while. During that period, the Repo GC rate slowly moved from the bottom of the fed funds target range to the top. By the end of 2018, Repo GC was actually trading above the target range.

However, things went sideways at the end of the 2018. During 2018 year-end, Repo GC spiked to 7.25%. Luckily, rates didn’t spike again over the next few months and the rate spike was attributed to, well, year-end. However, year-end 2018 was the harbinger of things to come. Nine months later, on September 17, 2019, Repo GC rates spiked again, trading as high as 9.25%. This event went down in the history books as the Repo market panic, the Repo rate spike, or the Repo rate crisis. The history books blame the rate spike on declining “bank reserves.”

That brings us to the current Balance Sheet Runoff. I can tell you what I believe will happen in the Repo market. The Repo market can pay for the securities. The securities can be financed. Think of the RRP facility as a giant “holding tank” of liquidity - $2.2 trillion worth. As securities come in, cash will be pulled out of the RRP to finance them. Assuming there’s about $178 billion arriving in the market each month, it will take about a year for the RRP to drain to zero.

Once the RRP is out of cash, the Repo market will need to attract cash from other short-term markets. Overnight Repo rates will migrate from the bottom of the fed funds target range to the top. Kind of like the last time.

Here’s an important point: There’s plenty of cash around because of the RRP facility, but who’s going to absorb all of those securities on their balance sheet? Someone needs to intermediate between the leveraged investors and the cash providers. Banks are already telling clients they will have balance sheet constraints on the horizon. They're warning clients that they have limited ability to increase their RWA,3 so clients can't count on funding increases.

This could be true, assuming banks are expected to intermediate a significant proportion of the new supply. Soon, banks will lobby the Fed to have the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) lifted. The last time the market absorbed a large number of government securities in a short period of time was during the COVID Crisis in March 2020.5 To help the banks intermediate, the Fed exempted them from the SLR from April 2020 to March 2021. For a year, banks had fewer balance sheet restrictions and, no surprise, they liked it!

Cash Market

That’s the situation in the Repo market. Unfortunately, the impact will be different in the cash market. There’s no “holding tank” of cash available to purchase securities like there is in the Repo market. The market needs to absorb the securities itself. Who will buy the Treasurys and MBS? Perhaps investment portfolios and some central banks. Maybe some corporate treasurers and some insurance companies. Not the Money Market Funds since the duration of the securities is too long. That leaves the hedge funds. The hedge funds will be buyers when there’s a Relative Value opportunity.

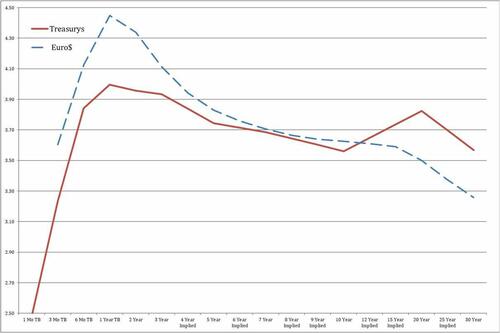

As more Treasurys and agencies arrive in the market, it will push the Treasury yield curve higher relative to other yield curves. Think about the impact of $1 trillion of supply coming into the market over the next six months. That’s $2 trillion over the next year and maybe $4 trillion of the next two years. It will create havoc in the financial markets. I believe Treasury rates can only go in one direction: higher.

Over the next few years, the government bond market will return to similar state as the 2017-2019 period. That was the last time the market was supersaturated with government securities. Back then, every hedge fund owned as many Treasurys as they possibly could. They hedged their long positions with futures and swaps. At the same time, every REIT owned as many agency MBS as they possibly could. There was a constant scramble for balance sheet. Everyone wanted more balance sheet because the wide spreads made fixedincome trading pretty easy. Repo rates were extremely volatile, especially over quarterend.

The Final Cut

That gets us back to the first question. If Balance Sheet Runoff will cause all of these problems, why run down the balance sheet at all? Why not just keep a massive balance sheet? All the Fed needs to do is declare that the size of the balance sheet is “appropriate” for the current size of the economy. However, maybe there are unintended consequences of a large balance sheet that no one is talking about?

Getting back to the Milton Friedman question. What if he was right? Or even partially correct? Milton Friedman launched the Monetarist approach to economic theory. "Helicopter Money," though often attributed to Ben Bernanke, was originally a Friedman idea. Without getting too much in the weeds, according to Friedman: ‘Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’

Currently, most officials and economists believe that raising interest rates will slow down the economy and cure inflation. If the current bout of inflation was due to high oil prices and “supply chains,” that’s a valid solution. If a significant component of inflation is from the liquidity that came from the QE program, then the Fed could keep raising rates, put us into a recession, and it still doesn’t fully solve the inflation problem.

Just for argument's sake, let's assume inflation is at least partially a monetary phenomenon. Maybe a percentage increase in the money supply doesn’t necessarily translate one-for-one into inflation, but there’s some impact. Pumping $5 trillion into the economy through QE purchases must have some effect on the price level. If you accept that some of that $5 trillion is driving some of the current inflation, then the solution to the inflation problem must include shrinking the balance sheet.

That means the inflation problem can’t be solved without withdrawing liquidity from the financial system. Therein lies the dilemma. If the Fed runs down the SOMA portfolio too much, they will break something in the market. If they don’t, we are stuck with inflation.

By Scott Skyrm, Executive Vice President at Curvature Securities

If you can answer two questions correctly, you might have a unique insight into the direction of monetary policy over the next few years.

-

Does the Fed really need to shrink the SOMA portfolio?

-

Was Milton Friedman right? Or at least partially right?

I sit in a unique position in the financial markets. I’ve been in the Repo market for over 30 years, seen the evolution of the Fed, government programs and how they affect the markets. I’ve seen tightening and easing cycles, crises and booms. Through all of the changes, there’s one thing that’s for sure: The Repo market is a window into what’s going on behind the scenes.

There’s a lot of concern about the fed funds rate right now. Keep in mind, the Fed moves this rate up and down. It was too low for a long time and it will eventually be too high. There might be a recession. Hopefully not. These all seem really important to the market right now, but they’re not the real risk. These are events we’ve experienced many times before. They’re a natural part of the financial markets. What’s important is the unknown unknown.

That’s the “wild card.” Right now, the risk lurking in the shadows is Balance Sheet Runoff. The Fed, the markets, the regulators, and even us Repo guys have limited experience with the Fed shrinking the balance sheet. Bottom line: there’s a risk that Balance Sheet Runoff will breaking something. On top of that, no one’s talking about it! [ZH: that’s not true, Mark Cabana has been talking about it for a long time]

Balance Sheet Runoff And New Issuance

The Federal Reserve began growing the SOMA portfolio through a series of Quantitative Easing (QE) programs that originally began in November 2008. The most recent program ran from September 2019 to March 2022. The size of the balance sheet peaked at $8.9 trillion in April 2022 and, shortly thereafter, the Fed announced SOMA portfolio Runoff. That is, they would no longer reinvest the principal and interest payments they receive from maturing securities. The Fed was supposed to let $47.5 billion Treasurys and agency MBS mature each month between June and August. Beginning in September, the Fed is supposed to let $95 billion a month Runoff. At this point, there’s no official end to the Runoff, but I expect it will continue until something breaks.

Think about $95 billion of Balance Sheet Runoff each month. That’s a massive amount of Treasury and agency securities entering the market. Now, when you consider net new Treasury issuance, there’s even more Treasury supply on the way. Though I’ve seen a range of estimates, let’s assume the government budget deficit is $1 trillion. That means there’s another $83 billion a month in new securities coming into the market. Combine Balance Sheet Runoff with net new Treasury issuance and we are looking at about $178 billion of securities coming into the market each month. Every month for the foreseeable future; no end in sight. Think of it this way, there will be $1 trillion more government securities in the market by March 2023. Where’s the cash coming from to pay for these securities? I might have the answer.

Original Sin

Hopefully, the Fed learned from their mistake. No, not the mistake the equity traders say about the Fed tightening too much. Of course, hindsight is 20/20, but clearly the Fed should have ended QE in 2021. In fact, April 2021 was the date when it should have ended. At that point, as the Fed continued buying, the market was sending the cash right back to the Fed through the RRP facility. Think of it this way: The Fed was injecting liquidity into the financial system and the market didn’t need that cash, so it gave it back to the Fed. Rule of thumb, when RRP volume increases during QE buying, the program is no longer effective

Last Time Around

Because QE overstayed its welcome, the Fed now needs to wrestle with an even larger balance sheet. The last time around, Balance Sheet Runoff didn’t quite go so well. During the 2017 to 2019 Runoff period, the Fed shrunk the SOMA portfolio from $4.3 trillion to $3.6 trillion – a total of about $700 billion. From 2017 through 2018, the market absorbed that supply without incident. At least for a while. During that period, the Repo GC rate slowly moved from the bottom of the fed funds target range to the top. By the end of 2018, Repo GC was actually trading above the target range.

However, things went sideways at the end of the 2018. During 2018 year-end, Repo GC spiked to 7.25%. Luckily, rates didn’t spike again over the next few months and the rate spike was attributed to, well, year-end. However, year-end 2018 was the harbinger of things to come. Nine months later, on September 17, 2019, Repo GC rates spiked again, trading as high as 9.25%. This event went down in the history books as the Repo market panic, the Repo rate spike, or the Repo rate crisis. The history books blame the rate spike on declining “bank reserves.”

That brings us to the current Balance Sheet Runoff. I can tell you what I believe will happen in the Repo market. The Repo market can pay for the securities. The securities can be financed. Think of the RRP facility as a giant “holding tank” of liquidity – $2.2 trillion worth. As securities come in, cash will be pulled out of the RRP to finance them. Assuming there’s about $178 billion arriving in the market each month, it will take about a year for the RRP to drain to zero.

Once the RRP is out of cash, the Repo market will need to attract cash from other short-term markets. Overnight Repo rates will migrate from the bottom of the fed funds target range to the top. Kind of like the last time.

Here’s an important point: There’s plenty of cash around because of the RRP facility, but who’s going to absorb all of those securities on their balance sheet? Someone needs to intermediate between the leveraged investors and the cash providers. Banks are already telling clients they will have balance sheet constraints on the horizon. They’re warning clients that they have limited ability to increase their RWA,3 so clients can’t count on funding increases.

This could be true, assuming banks are expected to intermediate a significant proportion of the new supply. Soon, banks will lobby the Fed to have the Supplementary Leverage Ratio (SLR) lifted. The last time the market absorbed a large number of government securities in a short period of time was during the COVID Crisis in March 2020.5 To help the banks intermediate, the Fed exempted them from the SLR from April 2020 to March 2021. For a year, banks had fewer balance sheet restrictions and, no surprise, they liked it!

Cash Market

That’s the situation in the Repo market. Unfortunately, the impact will be different in the cash market. There’s no “holding tank” of cash available to purchase securities like there is in the Repo market. The market needs to absorb the securities itself. Who will buy the Treasurys and MBS? Perhaps investment portfolios and some central banks. Maybe some corporate treasurers and some insurance companies. Not the Money Market Funds since the duration of the securities is too long. That leaves the hedge funds. The hedge funds will be buyers when there’s a Relative Value opportunity.

As more Treasurys and agencies arrive in the market, it will push the Treasury yield curve higher relative to other yield curves. Think about the impact of $1 trillion of supply coming into the market over the next six months. That’s $2 trillion over the next year and maybe $4 trillion of the next two years. It will create havoc in the financial markets. I believe Treasury rates can only go in one direction: higher.

Over the next few years, the government bond market will return to similar state as the 2017-2019 period. That was the last time the market was supersaturated with government securities. Back then, every hedge fund owned as many Treasurys as they possibly could. They hedged their long positions with futures and swaps. At the same time, every REIT owned as many agency MBS as they possibly could. There was a constant scramble for balance sheet. Everyone wanted more balance sheet because the wide spreads made fixedincome trading pretty easy. Repo rates were extremely volatile, especially over quarterend.

The Final Cut

That gets us back to the first question. If Balance Sheet Runoff will cause all of these problems, why run down the balance sheet at all? Why not just keep a massive balance sheet? All the Fed needs to do is declare that the size of the balance sheet is “appropriate” for the current size of the economy. However, maybe there are unintended consequences of a large balance sheet that no one is talking about?

Getting back to the Milton Friedman question. What if he was right? Or even partially correct? Milton Friedman launched the Monetarist approach to economic theory. “Helicopter Money,” though often attributed to Ben Bernanke, was originally a Friedman idea. Without getting too much in the weeds, according to Friedman: ‘Inflation is always and everywhere a monetary phenomenon.’

Currently, most officials and economists believe that raising interest rates will slow down the economy and cure inflation. If the current bout of inflation was due to high oil prices and “supply chains,” that’s a valid solution. If a significant component of inflation is from the liquidity that came from the QE program, then the Fed could keep raising rates, put us into a recession, and it still doesn’t fully solve the inflation problem.

Just for argument’s sake, let’s assume inflation is at least partially a monetary phenomenon. Maybe a percentage increase in the money supply doesn’t necessarily translate one-for-one into inflation, but there’s some impact. Pumping $5 trillion into the economy through QE purchases must have some effect on the price level. If you accept that some of that $5 trillion is driving some of the current inflation, then the solution to the inflation problem must include shrinking the balance sheet.

That means the inflation problem can’t be solved without withdrawing liquidity from the financial system. Therein lies the dilemma. If the Fed runs down the SOMA portfolio too much, they will break something in the market. If they don’t, we are stuck with inflation.