Currier & Ives

The U.S. border crisis has an historical underlay that is generally disregarded in analyses of the “illegal migrant crisis.”The U.S. border crisis has an historical underlay that is generally disregarded in analyses of the “illegal migrant crisis.” Unconscious as well as longstanding conflicts impact so-called current events. Most of the “migrants” are from Mexico and Central and South America, although clearly with the Biden-manipulated influx we also see cohorts of Chinese, Middle Eastern, and African “migrants.”

This writer saw about 20 “migrants” from Bangladesh and Pakistan being interviewed as they trekked into their new life. The interviewer asked them how they got here, and to a man (they were all men) they said they had walked. The interviewer was incredulous and asked, “From Pakistan?! How could you have walked from Pakistan?” But the migrant stuck to his guns and answered with a straight face, “Yes, we walked.” The role of NGO’s was not mentioned, nor flights, nor pocket money, nor meals, etc. etc.

Tensions over our Southern border with Mexico extend back to the 19th century. Mexico actually invited Americans to come settle in what was then Mexican territory in what is today northeastern Texas. Sam Houston and various frontiersmen accepted Mexico’s offer, but conflicts began and the Texas became independent of Mexico in 1836 which included the major defeat at San Jacinto of the Mexican forces led by Santa Ana by Houston’s Texans. Texas became an independent Republic of Texas from 1836 to 1845.

By 1844 President James Polk came into office and was committed to a doctrine of Manifest Destiny that promoted the idea that U.S. territory should expand dramatically across the continent beyond the vast territory that had been added by Jefferson’s Louisiana Purchase. This ideological position was based on a vision of democratic ideals and rights-based political philosophy that were uniquely American being put in place throughout the North American continent. Manifest Destiny was not a mere power play ideology as leftists often portray it.

The phrase “Manifest Destiny,” which emerged as the best-known expression of this mindset, first appeared in an editorial published in the July-August 1845 issue of The Democratic Review. In the editorial, the writer criticized the opposition that still lingered against the annexation of Texas, urging national unity on behalf of “the fulfillment of our manifest destiny to overspread the continent allotted by Providence for the free development of our yearly multiplying millions.” Here the key word is not “power” but “Providence.” This word is now rarely used, but the founding fathers of the USA and others following them were fond of this word because it communicated a sense of God-wrought expansion of the principles of sound governance based on Biblical values that were the hallmark of our founding and success as a nation.

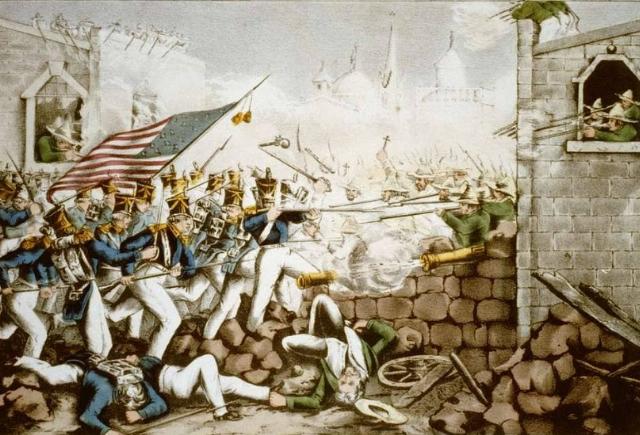

<img alt captext="Currier & Ives” class=”post-image-right” src=”https://conservativenewsbriefing.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/01/the-historical-enmity-between-spanish-and-english-culture.jpg” width=”450″>The crisis between Mexico and the U.S. came to a head in 1846 when U.S. troops crossed the Nueces River into the land area between the Nueces and the Rio Grande. The USA claimed the Rio Grande was the boundary between Mexico and the USA while Mexico claimed the Nueces was. Thus, the crossing of the Nueces by U.S. troops was adjudged by Mexico to be an act of war and the Mexican-American war began. Mexico lost the war and about one-third of its territory was taken by the USA, including nearly all of present-day California, Utah, New Mexico, and Arizona.

For this writer, the expansion of democratic political ideals claimed by Manifest Destiny actually pre-dates the 19th century and goes back to the adversarial relationship between Spain and England in the 16th century. That tension reached its climactic point during the reign of Elizabeth I. Plots were formed against her and after she supported the Dutch revolt against Spain, the opposition of Spain intensified.

Spain directed its fleet (Armada) to attack England in 1588. “Just after midnight on August 8, the English sent eight burning ships into the crowded harbor at Calais. The panicked Spanish ships were forced to cut their anchors and sail out to sea to avoid catching fire. The disorganized fleet, completely out of formation, was attacked by the English off Gravelines at dawn. In a decisive battle, the superior English guns won the day, and the devastated Armada was forced to retreat north to Scotland. The English navy pursued the Spanish as far as Scotland and then turned back for want of supplies. Battered by storms and suffering from a dire lack of supplies, the Armada sailed on a hard journey back to Spain around Scotland and Ireland.” That defeat of the Spanish marked the ascendancy of England as a great power.

Lastly, we should recall the Spanish-American War. Spain resisted the Cuban desire for independence, and this resistance threatened U.S. investments in Cuba at the end of the 19th century. In April 1898, Spain declared war on the U.S., but by December they had lost the war. Under the Treaty of Paris signed in December 1898, Spain renounced all claims to Cuba, ceded Guam and Puerto Rico to the United States, and transferred sovereignty over the Philippines to the United States for $20 million.

If we look at our southern border conflict within this wider historical context of there being a longstanding conflict with, Spanish-speaking people and English-speakers, we see a deeper dimension of our so-called “immigration crisis.” Certainly, the Democrats are looking for more voters who are dependent upon government and will cling to their left-wing programs and superficial philosophy. However, their interest has a deep historical context.

Our differences with the Spanish-speaking world are long-standing and real.

Image: Currier & Ives