Authored by Marina Zhang via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Billy was a bright 10-year-old boy with two Ivy-League-educated parents. He was book smart—got straight A’s in school—but lacked street smarts.

He was also a poor sport. Billy would frequently lie and cheat when playing board games or participating in team activities and have full-blown meltdowns when he lost. His friends, who had been with him since kindergarten, began losing patience. His parents recognized that something had to be done.

So Billy’s parents brought him to Dr. Victoria Dunckley, a pediatric psychiatrist specializing in screen use.

After a four-week “screen fast” prescribed by Dr. Dunckley, which eliminated all TVs, phones, and video games, Billy’s problems miraculously cleared up. His parents were so pleased that they decided to maintain the fast.

Six months passed, and Billy’s friends were no longer avoiding him, and his sportsmanship had improved markedly. Billy decided to run for class president and delivered a speech, something that would have previously terrified him.

Billy is one of Dr. Dunckley’s many patients whose mental and behavioral problems disappeared once they eliminated or significantly reduced screen time.

Excessive use of screens has become an epidemic silently eroding lives with little resistance. Gallup’s 2012 survey found that around 60 percent of young adults admit to spending too much of their time on the internet; a subsequent survey estimated that 83 percent of smartphone users say they keep their phone near them “almost all the time during their waking hours.”

Screens can overstimulate our brains, resulting in a perpetual, highly stressed, fight-or-flight state. This then makes us prone to meltdowns, depression, and anxiety when even minor changes in the environment occur.

Rising Problem

The initial link between screen time and poor mental health was spotted through generational studies by Jean Twenge, who has a doctorate in psychology and is a professor of psychology at San Diego State University.

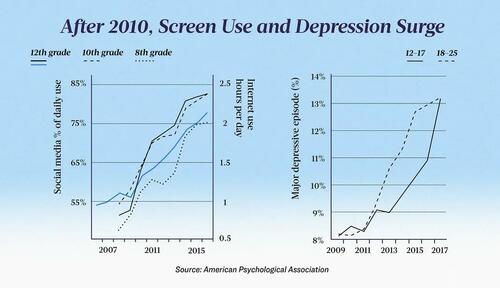

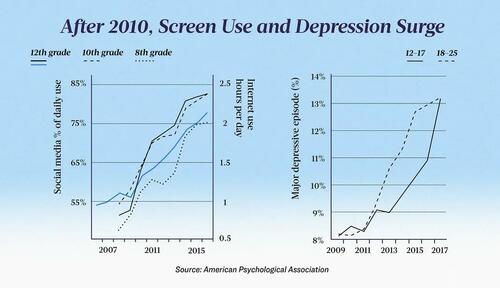

“I got used to changes that would grow slowly and steadily over time,“ but then after 2010, ”I started to see some changes that were much more sudden—I had really never seen anything like it,” Ms. Twenge said in a TEDx talk.

Between 2005 and 2012, the change in rates of depressive episodes in teens aged 12 to 17 barely exceeded 1 percent. However, between 2012 and 2017, there was an almost 4 percent increase.

Additionally, fewer teenagers are going outside or reading books, while their time on social media and the internet is dramatically surging.

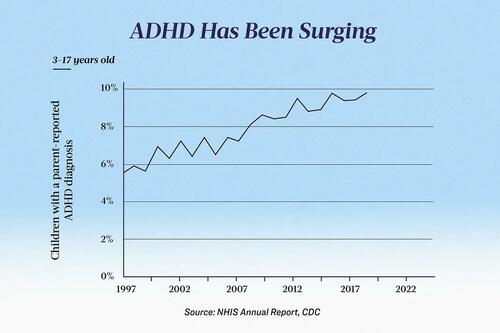

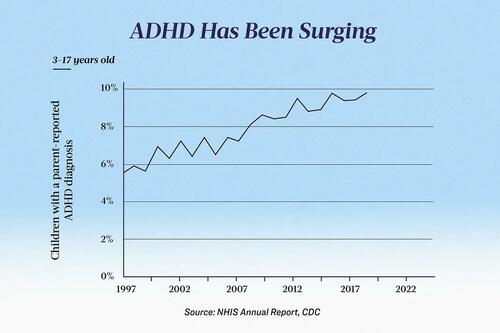

In 2008, psychotherapist Tom Kersting, who worked as a school counselor for 25 years, saw a rise in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses in children over age 8.

ADHD tends to be detected in early childhood after a child starts school. However, he has witnessed increasingly delayed diagnoses in teenagers and adults. While it could be possible that some of these teens were missed by clinicians when they were young, Mr. Kersting suspects that some developed symptoms of ADHD due to screen use.

Around 2012, when 30 percent of teenagers had a smartphone, he started to see rebellious behavior and anxiety disorders becoming more common among children. Young adults and teenagers growing up now also tend to be more antisocial and have reduced emotional resilience, which may be related to insufficient in-person socializing due to spending most of their time behind screens.

“It’s not just the amount of time spent in the cyber world,” Mr. Kersting told The Epoch Times, “but also what they missed out on: outside play and social learning.”

During the pandemic, adolescents’ screen time doubled.

Few studies investigated internet addiction in children during the pandemic, but a large study done in adults in 2021 showed that adults who were considered at risk of internet addiction were 2.3 times more likely to have depression and 1.9 times more likely to have anxiety than the general population. Furthermore, people with definite or severe addiction were 13 times more likely to have both depression and anxiety.

Fast forward to post-pandemic times, with teachers reporting that the latest generation—Gen Alpha, also known as “iPad kids”—is aggressive, undisciplined, and regulates emotions poorly in the classroom.

Dr. Clifford Sussman, a psychiatrist specializing in screen addiction, has focused his practice on treating this condition due to increasing need. Especially after the pandemic, “demand for help with this issue exploded,” he told The Epoch Times.

How Screens Hook You

Screen activities—whether they include video games, social media, internet scrolling, or video streaming—offer an escape. These activities are also highly stimulating for the brain due to their bright colors and seamless integration into the virtual world, professor and psychotherapist David Rosenfeld at Buenos Aires University told The Epoch Times.

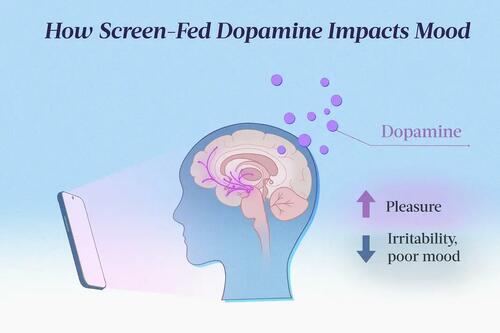

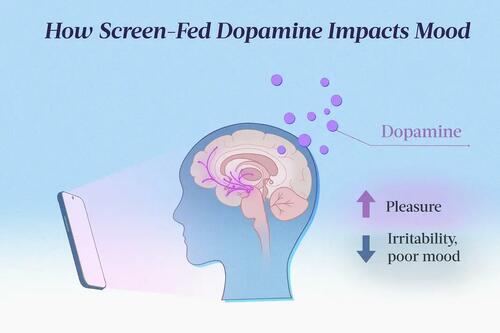

When presented with anything new and exciting, the brain releases dopamine, and anything that induces dopamine release can be addictive. Dopamine produces a feeling of pleasure, while a drop in it is linked to irritability and poor mood.

Screen activities have been designed to capture our attention by feeding us regular doses of dopamine. Like playing an immersive video game, giving you a thrill when you level up, defeat a boss, or find a new item, screens entice you to spend more time in the virtual world.

“Video games are governed by microscopic rules,” Bennett Foddy, who teaches game design at New York University’s Game Center, said in the book “Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked” by Adam Alter, as excerpted by The Guardian.

These micro-rules can be a “ding” sound or a white flash whenever a character moves over a particular square and are synced to the player’s actions so they feel they were the one who caused it. This micro-feedback generates a sense of reward, hooking people into continuously playing the game.

This system may also explain why interactive screen activities may be more problematic for children than passive screen activities, like watching TV.

Dr. Dunckley has observed that while two hours of TV is linked to signs of dysregulation in children, only 30 minutes of interactive screen activities is stimulating enough for signs to occur.

Many video games also employ strategies used in gambling, such as loot-box rewards, where players are rewarded at random intervals throughout the game. Since players do not know when the next reward drop will come, they are further compelled to play the game—even if they are not enjoying it.

This strategy came from the works of psychologist Burrhus Frederic Skinner. Skinner put pigeons in a box with a button, rewarding them with food whenever they pressed it. He found that the pigeons rewarded irregularly were more compelled to press the button than those rewarded with every button press.

This compulsion also exists in humans.

Read more here...

Authored by Marina Zhang via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Billy was a bright 10-year-old boy with two Ivy-League-educated parents. He was book smart—got straight A’s in school—but lacked street smarts.

He was also a poor sport. Billy would frequently lie and cheat when playing board games or participating in team activities and have full-blown meltdowns when he lost. His friends, who had been with him since kindergarten, began losing patience. His parents recognized that something had to be done.

So Billy’s parents brought him to Dr. Victoria Dunckley, a pediatric psychiatrist specializing in screen use.

After a four-week “screen fast” prescribed by Dr. Dunckley, which eliminated all TVs, phones, and video games, Billy’s problems miraculously cleared up. His parents were so pleased that they decided to maintain the fast.

Six months passed, and Billy’s friends were no longer avoiding him, and his sportsmanship had improved markedly. Billy decided to run for class president and delivered a speech, something that would have previously terrified him.

Billy is one of Dr. Dunckley’s many patients whose mental and behavioral problems disappeared once they eliminated or significantly reduced screen time.

Excessive use of screens has become an epidemic silently eroding lives with little resistance. Gallup’s 2012 survey found that around 60 percent of young adults admit to spending too much of their time on the internet; a subsequent survey estimated that 83 percent of smartphone users say they keep their phone near them “almost all the time during their waking hours.”

Screens can overstimulate our brains, resulting in a perpetual, highly stressed, fight-or-flight state. This then makes us prone to meltdowns, depression, and anxiety when even minor changes in the environment occur.

Rising Problem

The initial link between screen time and poor mental health was spotted through generational studies by Jean Twenge, who has a doctorate in psychology and is a professor of psychology at San Diego State University.

“I got used to changes that would grow slowly and steadily over time,“ but then after 2010, ”I started to see some changes that were much more sudden—I had really never seen anything like it,” Ms. Twenge said in a TEDx talk.

Between 2005 and 2012, the change in rates of depressive episodes in teens aged 12 to 17 barely exceeded 1 percent. However, between 2012 and 2017, there was an almost 4 percent increase.

Additionally, fewer teenagers are going outside or reading books, while their time on social media and the internet is dramatically surging.

In 2008, psychotherapist Tom Kersting, who worked as a school counselor for 25 years, saw a rise in attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) diagnoses in children over age 8.

ADHD tends to be detected in early childhood after a child starts school. However, he has witnessed increasingly delayed diagnoses in teenagers and adults. While it could be possible that some of these teens were missed by clinicians when they were young, Mr. Kersting suspects that some developed symptoms of ADHD due to screen use.

Around 2012, when 30 percent of teenagers had a smartphone, he started to see rebellious behavior and anxiety disorders becoming more common among children. Young adults and teenagers growing up now also tend to be more antisocial and have reduced emotional resilience, which may be related to insufficient in-person socializing due to spending most of their time behind screens.

“It’s not just the amount of time spent in the cyber world,” Mr. Kersting told The Epoch Times, “but also what they missed out on: outside play and social learning.”

During the pandemic, adolescents’ screen time doubled.

Few studies investigated internet addiction in children during the pandemic, but a large study done in adults in 2021 showed that adults who were considered at risk of internet addiction were 2.3 times more likely to have depression and 1.9 times more likely to have anxiety than the general population. Furthermore, people with definite or severe addiction were 13 times more likely to have both depression and anxiety.

Fast forward to post-pandemic times, with teachers reporting that the latest generation—Gen Alpha, also known as “iPad kids”—is aggressive, undisciplined, and regulates emotions poorly in the classroom.

Dr. Clifford Sussman, a psychiatrist specializing in screen addiction, has focused his practice on treating this condition due to increasing need. Especially after the pandemic, “demand for help with this issue exploded,” he told The Epoch Times.

How Screens Hook You

Screen activities—whether they include video games, social media, internet scrolling, or video streaming—offer an escape. These activities are also highly stimulating for the brain due to their bright colors and seamless integration into the virtual world, professor and psychotherapist David Rosenfeld at Buenos Aires University told The Epoch Times.

When presented with anything new and exciting, the brain releases dopamine, and anything that induces dopamine release can be addictive. Dopamine produces a feeling of pleasure, while a drop in it is linked to irritability and poor mood.

Screen activities have been designed to capture our attention by feeding us regular doses of dopamine. Like playing an immersive video game, giving you a thrill when you level up, defeat a boss, or find a new item, screens entice you to spend more time in the virtual world.

“Video games are governed by microscopic rules,” Bennett Foddy, who teaches game design at New York University’s Game Center, said in the book “Irresistible: The Rise of Addictive Technology and the Business of Keeping Us Hooked” by Adam Alter, as excerpted by The Guardian.

These micro-rules can be a “ding” sound or a white flash whenever a character moves over a particular square and are synced to the player’s actions so they feel they were the one who caused it. This micro-feedback generates a sense of reward, hooking people into continuously playing the game.

This system may also explain why interactive screen activities may be more problematic for children than passive screen activities, like watching TV.

Dr. Dunckley has observed that while two hours of TV is linked to signs of dysregulation in children, only 30 minutes of interactive screen activities is stimulating enough for signs to occur.

Many video games also employ strategies used in gambling, such as loot-box rewards, where players are rewarded at random intervals throughout the game. Since players do not know when the next reward drop will come, they are further compelled to play the game—even if they are not enjoying it.

This strategy came from the works of psychologist Burrhus Frederic Skinner. Skinner put pigeons in a box with a button, rewarding them with food whenever they pressed it. He found that the pigeons rewarded irregularly were more compelled to press the button than those rewarded with every button press.

This compulsion also exists in humans.

Read more here…

Loading…