Authored by Eva Fu via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Locked inside the crowded Chinese prison, blind lawyer Chen Guancheng hid his most treasured possession from the guards - inside a single serve milk box.

A pocket-size shortwave radio.

For three years, Mr. Chen looked forward to the hours after curfew. With a blanket wrapped over his head and the radio’s metal antenna parallel to his body, he lay still as the vibrating device under his ear brought to life a world outside the prison’s walls. Petitioners, protesters, human rights abuses, a grassroots movement to cut ties with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—in that tiny murmuring voice, he saw them all. He was free.

Over the decade since Mr. Chen escaped to the United States, the pool of Western broadcasters for information-hungry Chinese like him has shrunk considerably.

Radio powerhouses—BBC, Deutsche Welle, Voice of America—have either cut back on their China service or moved programs online. Meanwhile, the “Great Firewall,” the regime’s censorship apparatus aimed at isolating China digitally, seems only to grow taller by the day.

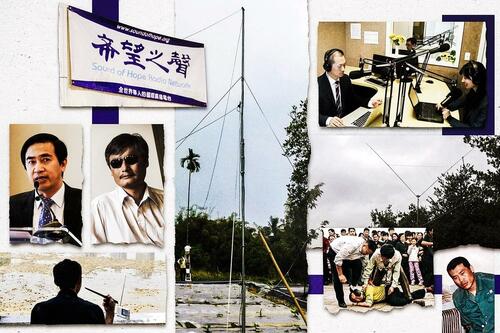

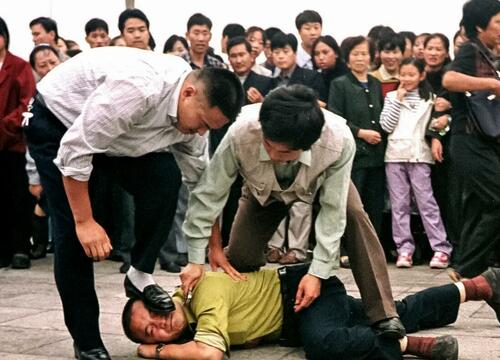

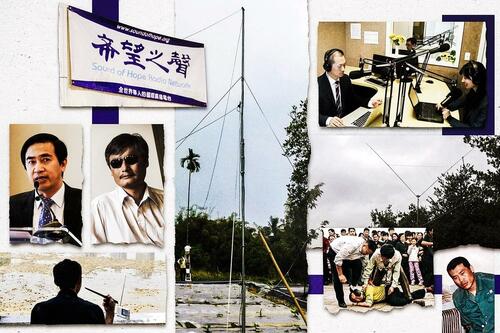

Bucking the trend is a largely volunteer-run radio network called Sound of Hope, whose 10 p.m. and midnight segments kept Mr. Chen informed about current affairs in China during his years in prison.

The company now boasts one of the largest shortwave broadcasting networks around China, with about 120 stations beaming signals to China 24/7.

Allen Zeng, Sound of Hope’s co-founder and CEO, sees shortwave as the answer to the regime’s information blackout.

“They can turn off the internet, carry out the killing, wash clean the blood, and turn it back on,” he told The Epoch Times, pointing to Iran’s pattern of blocking the internet during nationwide protests.

With shortwave radio, though, “they have nowhere to turn it off,” Mr. Zeng said.

“It’s like the rain falling down from the sky—they have no way to block the sky.”

A Voice to Trust

An unlikely journey began in 2004 for Mr. Zeng, then a Silicon Valley engineer.

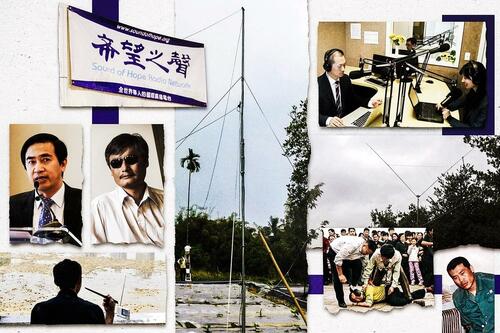

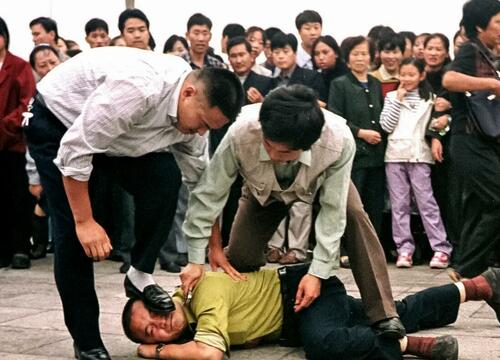

Inside China, a massive nationwide campaign had been underway, targeting virtually one in 13 Chinese who live by truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, the three tenets of the faith group Falun Gong.

Arbitrary jailing, slave labor, the abuse of psychiatric drugs, and sexual abuse—the stories trickling out of China were sickening enough that Mr. Zeng and a team of like-minded Chinese expats felt they could no longer stand by.

“We had to do something about it. We needed to stop the killing,” he said.

The first thing that came to mind was the shortwave radio that had been a household item in China since the Cold War era, one that in 1989, Mr. Zeng and other college students had turned to for information when authorities rolled their tanks over democracy-loving demonstrators in Tiananmen Square.

“Because nothing else could be trusted,” he said.

With little budget and know-how, the team started small: leasing one hour of airtime from Taiwanese national broadcaster Radio Taiwan International.

Around that time, “Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party,” an Epoch Times editorial series that unpacked the nature of the Chinese regime, had just been published, and Sound of Hope took it to audio.

It was such a hit in Beijing that shortwave radios were out of stock for months.

The response, and occasional words of encouragement from listeners who managed to bypass China’s internet censorship, kept Mr. Zeng’s team going. Dissidents chipped in and programs diversified. Soon, they were Radio Taiwan International’s biggest contractor.

Gauging the size of the network’s audience is difficult given the opacity of data from China.

But Sound of Hope became so influential that it caught Beijing’s attention. The Chinese regime began to pressure the radio network’s Taiwanese partner.

Eventually, the Taiwanese broadcaster backed out. Sound of Hope was back to square one.

‘Walking in the Dark’

Giving up wasn’t in Mr. Zeng’s vocabulary.

As the partnership with Taiwan unraveled, the engineers raced to develop their own solutions. They drew inspiration from fishing vessels’ radio waves to build their own transmitter.

The result was a mini-tower based in Taiwan with upward-facing antennas that spread out like wings. They nicknamed it “Seagull.”

The team set its sights low. The first “seagull” had a power level of 100 watts—a thousandth of the smallest radio service they had leased from the Taiwanese broadcaster.

“It was the only thing we could afford,” Mr. Zeng said.

“Seagull” No. 1 was short-lived, and so were many of its successors whose signals the Chinese authorities quickly jammed. But to the team, it was a major discovery: At 100 watts, they still had a chance to be heard.

They kept producing and tweaking their equipment with each new creation.

“It was just like walking in the dark—we didn’t know whether there would be an end to this tunnel,” Mr. Zeng said.

Finally, on the 16th try, they saw a breakthrough. The signal broke through and held steady.

Mr. Zeng figured that they had, for the moment, consumed all the jamming power from China.

“We outgunned them pretty much,” he said. “They cannot move as fast as we did.”

Expansion

Technical challenges aside, getting the stations to work was no easy feat.

The wilderness, their best location for an uninterrupted signal, is also a haven for creepy crawlies, from scorpions to snakes. Hsieh Shih-mu, a volunteer, stepped on a snake once and sighted many more while building some of the earliest “seagulls” in Taiwan’s southern tip. Often, after wobbling back home on a motorcycle on the pitch-black mountain road, he was covered in mosquito bites.

Narrow and muddy, the path became doubly treacherous after rain. One time, another volunteer nearly fell off the hill—and would have, if not for the roadside tree branches that caught his motorcycle. They had to call a tow truck to haul the man back up.

Read more here...

Authored by Eva Fu via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

Locked inside the crowded Chinese prison, blind lawyer Chen Guancheng hid his most treasured possession from the guards – inside a single serve milk box.

A pocket-size shortwave radio.

For three years, Mr. Chen looked forward to the hours after curfew. With a blanket wrapped over his head and the radio’s metal antenna parallel to his body, he lay still as the vibrating device under his ear brought to life a world outside the prison’s walls. Petitioners, protesters, human rights abuses, a grassroots movement to cut ties with the Chinese Communist Party (CCP)—in that tiny murmuring voice, he saw them all. He was free.

Over the decade since Mr. Chen escaped to the United States, the pool of Western broadcasters for information-hungry Chinese like him has shrunk considerably.

Radio powerhouses—BBC, Deutsche Welle, Voice of America—have either cut back on their China service or moved programs online. Meanwhile, the “Great Firewall,” the regime’s censorship apparatus aimed at isolating China digitally, seems only to grow taller by the day.

Bucking the trend is a largely volunteer-run radio network called Sound of Hope, whose 10 p.m. and midnight segments kept Mr. Chen informed about current affairs in China during his years in prison.

The company now boasts one of the largest shortwave broadcasting networks around China, with about 120 stations beaming signals to China 24/7.

Allen Zeng, Sound of Hope’s co-founder and CEO, sees shortwave as the answer to the regime’s information blackout.

“They can turn off the internet, carry out the killing, wash clean the blood, and turn it back on,” he told The Epoch Times, pointing to Iran’s pattern of blocking the internet during nationwide protests.

With shortwave radio, though, “they have nowhere to turn it off,” Mr. Zeng said.

“It’s like the rain falling down from the sky—they have no way to block the sky.”

A Voice to Trust

An unlikely journey began in 2004 for Mr. Zeng, then a Silicon Valley engineer.

Inside China, a massive nationwide campaign had been underway, targeting virtually one in 13 Chinese who live by truthfulness, compassion, and tolerance, the three tenets of the faith group Falun Gong.

Arbitrary jailing, slave labor, the abuse of psychiatric drugs, and sexual abuse—the stories trickling out of China were sickening enough that Mr. Zeng and a team of like-minded Chinese expats felt they could no longer stand by.

“We had to do something about it. We needed to stop the killing,” he said.

The first thing that came to mind was the shortwave radio that had been a household item in China since the Cold War era, one that in 1989, Mr. Zeng and other college students had turned to for information when authorities rolled their tanks over democracy-loving demonstrators in Tiananmen Square.

“Because nothing else could be trusted,” he said.

With little budget and know-how, the team started small: leasing one hour of airtime from Taiwanese national broadcaster Radio Taiwan International.

Around that time, “Nine Commentaries on the Communist Party,” an Epoch Times editorial series that unpacked the nature of the Chinese regime, had just been published, and Sound of Hope took it to audio.

It was such a hit in Beijing that shortwave radios were out of stock for months.

The response, and occasional words of encouragement from listeners who managed to bypass China’s internet censorship, kept Mr. Zeng’s team going. Dissidents chipped in and programs diversified. Soon, they were Radio Taiwan International’s biggest contractor.

Gauging the size of the network’s audience is difficult given the opacity of data from China.

But Sound of Hope became so influential that it caught Beijing’s attention. The Chinese regime began to pressure the radio network’s Taiwanese partner.

Eventually, the Taiwanese broadcaster backed out. Sound of Hope was back to square one.

‘Walking in the Dark’

Giving up wasn’t in Mr. Zeng’s vocabulary.

As the partnership with Taiwan unraveled, the engineers raced to develop their own solutions. They drew inspiration from fishing vessels’ radio waves to build their own transmitter.

The result was a mini-tower based in Taiwan with upward-facing antennas that spread out like wings. They nicknamed it “Seagull.”

The team set its sights low. The first “seagull” had a power level of 100 watts—a thousandth of the smallest radio service they had leased from the Taiwanese broadcaster.

“It was the only thing we could afford,” Mr. Zeng said.

“Seagull” No. 1 was short-lived, and so were many of its successors whose signals the Chinese authorities quickly jammed. But to the team, it was a major discovery: At 100 watts, they still had a chance to be heard.

They kept producing and tweaking their equipment with each new creation.

“It was just like walking in the dark—we didn’t know whether there would be an end to this tunnel,” Mr. Zeng said.

Finally, on the 16th try, they saw a breakthrough. The signal broke through and held steady.

Mr. Zeng figured that they had, for the moment, consumed all the jamming power from China.

“We outgunned them pretty much,” he said. “They cannot move as fast as we did.”

Expansion

Technical challenges aside, getting the stations to work was no easy feat.

The wilderness, their best location for an uninterrupted signal, is also a haven for creepy crawlies, from scorpions to snakes. Hsieh Shih-mu, a volunteer, stepped on a snake once and sighted many more while building some of the earliest “seagulls” in Taiwan’s southern tip. Often, after wobbling back home on a motorcycle on the pitch-black mountain road, he was covered in mosquito bites.

Narrow and muddy, the path became doubly treacherous after rain. One time, another volunteer nearly fell off the hill—and would have, if not for the roadside tree branches that caught his motorcycle. They had to call a tow truck to haul the man back up.

Read more here…

Loading…