Authored by Walker Larson via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

The president’s desk bears a remarkable pedigree. Its story ties together several disparate historical threads, including a ghost ship, polar exploration, and relations between the United States and the UK. The tale begins with a certain British Admiral, Sir Edward Belch.

A mapmaker in the British Royal Navy described Sir Edward Belcher as “a tyrannical martinet who made every ship he commanded a floating hell.” In 1854, that hell was a cold one, since Belcher and his small flotilla were sailing the frigid seas of the Arctic.

Tyrannical or not, one thing is sure: Belcher was a talented seaman, explorer, and hydrographer (someone who maps bodies of water). In 1852, he'd been assigned an important task. Belcher and his men ventured into the austere, alien waters of the Arctic on a rescue mission, searching for any trace of the lost Franklin Expedition.

The Franklin Expedition, headed by Sir John Franklin, was an 1845 British exploration operation that aimed to find the Northwest Passage through Canada to the Pacific. Franklin’s crew was ordered to record magnetic data as a potential aid to navigation practices. But the treacherous northern sea closed its icy fingers around the men of the expedition and never let them go. The mission proved to be one of the worst disasters in the history of polar exploration.

The two ships of the Franklin expedition—the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror—sailed from Britain in May of 1845, took on supplies in Greenland in July, were spotted in Baffin Bay, Canada, and crossed the Lancaster Sound. They were never heard from again, vanishing into the vast white void.

In the years of searching conducted by the British government after their disappearance, no trace of the ships was found. Only a few artifacts and human remains were recovered. Most of the 129 crew members and officers had simply disappeared. Forensic investigations were conducted on the recovered bodies, revealing that the men suffered from starvation, scurvy, lead poisoning, and, possibly, cannibalism, a narrative supported by the oral accounts of the expedition provided by the Inuit people. It was only in the 2010s that the Erebus and the Terror were at last discovered, wrecked off King William Island.

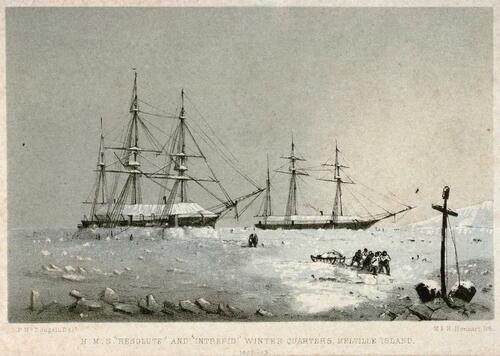

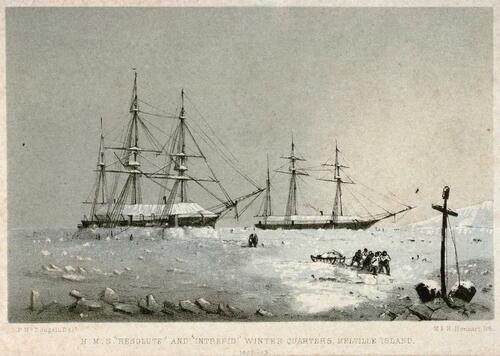

It was this polar tragedy that brought Sir Edward Belcher and his small fleet of ships, including the HMS Resolute, to the Arctic in 1854. Belcher’s voyage was almost as ill-fated as Franklin’s. Though the Resolute was heavily constructed to withstand the harsh Arctic environment, it became locked in the ice in 1854, along with four more of Belcher’s ships. Belcher made the difficult decision to abandon the ships and begin an overland trek to rendezvous with other vessels that could bring them back to England.

The men left behind their floating piece of home, their security and warmth, and entered the unending whiteness. They marched over the vast expanses of ice, eventually meeting up with their comrades’ ships and returning safely to England. There, Belcher was court-martialed (not for the first time) for abandoning his vessels but acquitted because his orders gave him full discretion. He never received another command.

So there, in the emptiness of the frozen North Sea, where the slowly clenching jaws of ice groaned and echoed through frigid air, the pale winds pined, and the strange lights flickered and played about the sky like ghosts, the abandoned Resolute waited. Belcher and his men had left it in good order, though they knew it would likely be broken up by the ice, in the end. But that was not to be its fate.

Months passed. Summer came, kissing even the hard northern waters with warmth. The ice thawed. Somehow, Resolute broke free. It drifted some 1,200 miles until James Buddington, captain of an American whaling ship, the George Henry, sighted it in 1855, near Baffin Island. An 1856 New York Journal article describes the moment the Americans boarded the ghost ship.

“Finally, stealing over the side, they found everything stowed away in proper order. ... Everything wore the silence of the tomb. Finally reaching the cabin door they broke in and found their way in the darkness to the table ... [a candle] was lit and before the astonished gaze of these men exposed a scene that appeared to be rather one of enchantment than reality. Upon a massive table was a metal teapot, glistening as if new, also a large volume of Scott’s family Bible, together with glasses and decanters filled with choice liquors. Nearby was Captain Kellett’s chair, a piece of massive furniture, over which had been thrown, as if to protect this seat from vulgar occupation, the royal flag of Great Britain.”

Buddington assigned a portion of his crew to the ghost ship, and they sailed it back to the United States. According to maritime law, the ship belonged to those who had found her (Buddington and his crew), and the British government accepted this fact when they were notified of the find. But the U.S. government had a different idea.

At this time, U.S. relations with Great Britain were strained. The War of 1812 was still alive to memory, including the moment when the British burned the U.S. capitol. The two countries continued to dispute the Canadian border. In the discovery of the Resolute, the U.S. government saw an opportunity to make a gesture of goodwill toward their adversaries across the pond. Congress authorized $40,000 to purchase the ship from Buddington and repair it.

The Americans took great care in refurbishing the sturdy old juggernaut, as described in an 1856 New York Times article:

“With such completeness and attention to detail has this work been performed, that not only has everything found on board been preserved, even to the books in the captain’s library, the pictures in his cabin, and a musical-box and organ belonging to other officers, but new British flags have been manufactured in the Navy Yard to take the place of those which had rotted during the long time she was without a living soul on board.”

With great fanfare, the Resolute was sailed back to England and presented as a gift to Queen Victoria, who visited the ship in person. The Brits took the gift to heart, and the queen remembered this gesture from the Americans for many years.

Returning the Favor

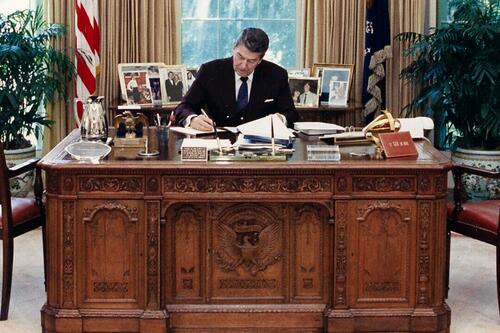

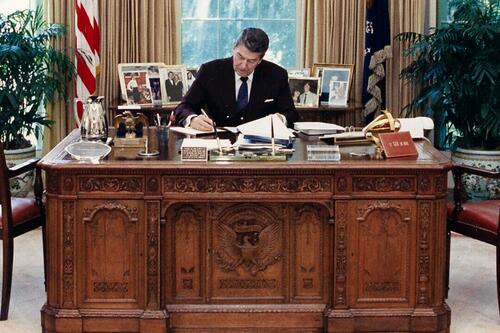

When the Resolute was removed from service and broken down in 1879, Queen Victoria ordered some of its timbers to be preserved. The heavy oak lumber, which had weathered so many storms and seen both tragedy and reconciliation, was constructed into a massive, ornate desk, weighing 1,300 pounds. Victoria sent it as a surprise gift to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880, returning the favor and expressing gratitude for returning Her Majesty’s Ship, the Resolute, all those years before. Most importantly, the desk became an emblem of the mutual goodwill and alliance between the United States and Great Britain, which has never wavered since.

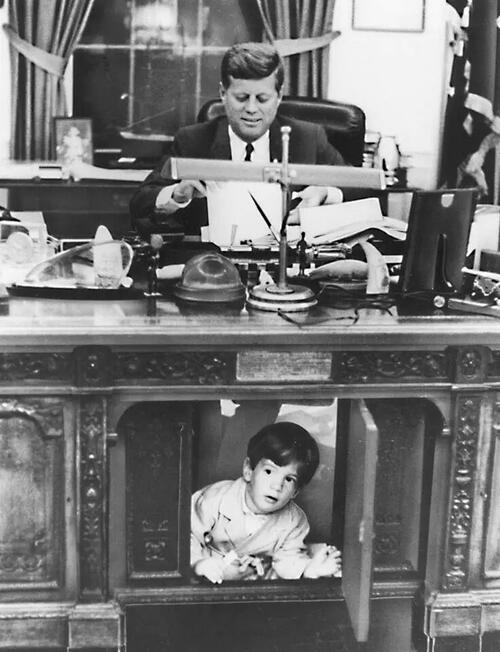

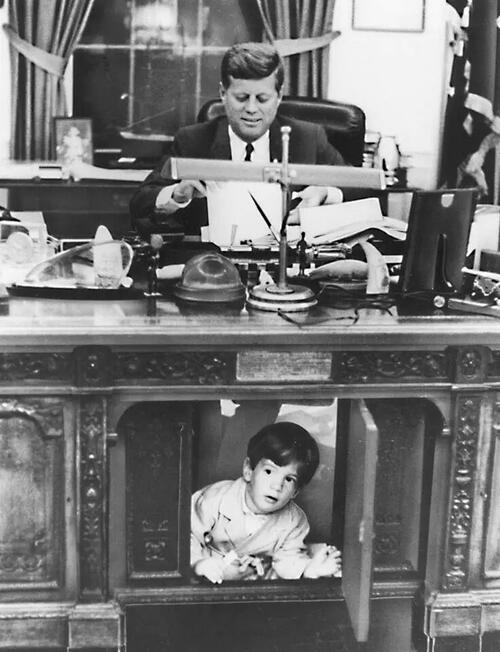

Most U.S. Presidents used the desk since it was gifted at the end of the 19th century. Between 1951 and 1962, it was used to hold a projector in the broadcast room at the White House until it was rediscovered by First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. She had it moved back to the Oval Office, where it has formed part of the backdrop for many landmark moments in American presidential history. There are photos of President Kennedy sitting at the desk with John Kennedy Jr. peeking out from beneath it.

The Resolute desk, as it has come to be known, bears within it the marks of struggle, abandonment, miraculous discovery, restoration, and reconciliation. It’s a fitting symbol for the resolute American spirit.

Authored by Walker Larson via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

The president’s desk bears a remarkable pedigree. Its story ties together several disparate historical threads, including a ghost ship, polar exploration, and relations between the United States and the UK. The tale begins with a certain British Admiral, Sir Edward Belch.

A mapmaker in the British Royal Navy described Sir Edward Belcher as “a tyrannical martinet who made every ship he commanded a floating hell.” In 1854, that hell was a cold one, since Belcher and his small flotilla were sailing the frigid seas of the Arctic.

Tyrannical or not, one thing is sure: Belcher was a talented seaman, explorer, and hydrographer (someone who maps bodies of water). In 1852, he’d been assigned an important task. Belcher and his men ventured into the austere, alien waters of the Arctic on a rescue mission, searching for any trace of the lost Franklin Expedition.

The Franklin Expedition, headed by Sir John Franklin, was an 1845 British exploration operation that aimed to find the Northwest Passage through Canada to the Pacific. Franklin’s crew was ordered to record magnetic data as a potential aid to navigation practices. But the treacherous northern sea closed its icy fingers around the men of the expedition and never let them go. The mission proved to be one of the worst disasters in the history of polar exploration.

The two ships of the Franklin expedition—the HMS Erebus and HMS Terror—sailed from Britain in May of 1845, took on supplies in Greenland in July, were spotted in Baffin Bay, Canada, and crossed the Lancaster Sound. They were never heard from again, vanishing into the vast white void.

In the years of searching conducted by the British government after their disappearance, no trace of the ships was found. Only a few artifacts and human remains were recovered. Most of the 129 crew members and officers had simply disappeared. Forensic investigations were conducted on the recovered bodies, revealing that the men suffered from starvation, scurvy, lead poisoning, and, possibly, cannibalism, a narrative supported by the oral accounts of the expedition provided by the Inuit people. It was only in the 2010s that the Erebus and the Terror were at last discovered, wrecked off King William Island.

It was this polar tragedy that brought Sir Edward Belcher and his small fleet of ships, including the HMS Resolute, to the Arctic in 1854. Belcher’s voyage was almost as ill-fated as Franklin’s. Though the Resolute was heavily constructed to withstand the harsh Arctic environment, it became locked in the ice in 1854, along with four more of Belcher’s ships. Belcher made the difficult decision to abandon the ships and begin an overland trek to rendezvous with other vessels that could bring them back to England.

The men left behind their floating piece of home, their security and warmth, and entered the unending whiteness. They marched over the vast expanses of ice, eventually meeting up with their comrades’ ships and returning safely to England. There, Belcher was court-martialed (not for the first time) for abandoning his vessels but acquitted because his orders gave him full discretion. He never received another command.

So there, in the emptiness of the frozen North Sea, where the slowly clenching jaws of ice groaned and echoed through frigid air, the pale winds pined, and the strange lights flickered and played about the sky like ghosts, the abandoned Resolute waited. Belcher and his men had left it in good order, though they knew it would likely be broken up by the ice, in the end. But that was not to be its fate.

Months passed. Summer came, kissing even the hard northern waters with warmth. The ice thawed. Somehow, Resolute broke free. It drifted some 1,200 miles until James Buddington, captain of an American whaling ship, the George Henry, sighted it in 1855, near Baffin Island. An 1856 New York Journal article describes the moment the Americans boarded the ghost ship.

“Finally, stealing over the side, they found everything stowed away in proper order. … Everything wore the silence of the tomb. Finally reaching the cabin door they broke in and found their way in the darkness to the table … [a candle] was lit and before the astonished gaze of these men exposed a scene that appeared to be rather one of enchantment than reality. Upon a massive table was a metal teapot, glistening as if new, also a large volume of Scott’s family Bible, together with glasses and decanters filled with choice liquors. Nearby was Captain Kellett’s chair, a piece of massive furniture, over which had been thrown, as if to protect this seat from vulgar occupation, the royal flag of Great Britain.”

Buddington assigned a portion of his crew to the ghost ship, and they sailed it back to the United States. According to maritime law, the ship belonged to those who had found her (Buddington and his crew), and the British government accepted this fact when they were notified of the find. But the U.S. government had a different idea.

At this time, U.S. relations with Great Britain were strained. The War of 1812 was still alive to memory, including the moment when the British burned the U.S. capitol. The two countries continued to dispute the Canadian border. In the discovery of the Resolute, the U.S. government saw an opportunity to make a gesture of goodwill toward their adversaries across the pond. Congress authorized $40,000 to purchase the ship from Buddington and repair it.

The Americans took great care in refurbishing the sturdy old juggernaut, as described in an 1856 New York Times article:

“With such completeness and attention to detail has this work been performed, that not only has everything found on board been preserved, even to the books in the captain’s library, the pictures in his cabin, and a musical-box and organ belonging to other officers, but new British flags have been manufactured in the Navy Yard to take the place of those which had rotted during the long time she was without a living soul on board.”

With great fanfare, the Resolute was sailed back to England and presented as a gift to Queen Victoria, who visited the ship in person. The Brits took the gift to heart, and the queen remembered this gesture from the Americans for many years.

Returning the Favor

When the Resolute was removed from service and broken down in 1879, Queen Victoria ordered some of its timbers to be preserved. The heavy oak lumber, which had weathered so many storms and seen both tragedy and reconciliation, was constructed into a massive, ornate desk, weighing 1,300 pounds. Victoria sent it as a surprise gift to President Rutherford B. Hayes in 1880, returning the favor and expressing gratitude for returning Her Majesty’s Ship, the Resolute, all those years before. Most importantly, the desk became an emblem of the mutual goodwill and alliance between the United States and Great Britain, which has never wavered since.

Most U.S. Presidents used the desk since it was gifted at the end of the 19th century. Between 1951 and 1962, it was used to hold a projector in the broadcast room at the White House until it was rediscovered by First Lady Jacqueline Kennedy. She had it moved back to the Oval Office, where it has formed part of the backdrop for many landmark moments in American presidential history. There are photos of President Kennedy sitting at the desk with John Kennedy Jr. peeking out from beneath it.

The Resolute desk, as it has come to be known, bears within it the marks of struggle, abandonment, miraculous discovery, restoration, and reconciliation. It’s a fitting symbol for the resolute American spirit.

Loading…