Submitted by Brent Johnson and Michael Peregrine of Santiago Capital.

Executive Summary

Currency carry trades, while seemingly straightforward, carry significant risks due to their reliance on interest rate differentials between countries. Investors borrow in a low-interest currency, like the yen, to invest in higher-yielding assets.

These trades are often unhedged and leveraged, magnifying potential profits but also exposing investors to substantial risks, especially if interest rates or currency values shift unexpectedly. The biggest risk is the implicit assumption that these differentials will remain stable, which rarely holds true over the long term.

Historically, even fixed currency pegs, such as those attempted by the Swiss National Bank and the Bank of England, have failed due to unsustainable capital flows. Despite the lessons learned from past failures, such as when the U.S. decoupled the dollar from the gold standard in 1971, investors are often lured by the allure of stable, easy returns from carry trades.

However, carry trades can appear benign for years before unraveling catastrophically, leading to sudden and severe market volatility. This was the case in the recent yen carry trade crisis of August 2024.

The BoJ now faces a dilemma: Do they protect the Yen with higher interest rates? Or protect the Japanese government bond market with lower rates.

They cannot do both.

This is because the tools used to protect their currency conflict with the tools used to protect the bond market. And vice versa.

To protect a currency, A central bank will typically raise interest rates to make the currency more attractive to investors, which can help stabilize or increase its value. However, higher interest rates increase borrowing costs, leading to lower bond prices and rising yields, which can destabilize the bond market. This dynamic creates a policy dilemma, particularly in economies heavily reliant on debt, as higher yields can hurt economic growth and raise concerns about government debt sustainability.

On the other hand, protecting the bond market requires central banks to keep interest rates low, which supports bond prices and keeps borrowing costs manageable for governments and businesses. However, lower interest rates tend to weaken a currency by making it less attractive to investors seeking higher returns. A weaker currency can fuel inflation by increasing the cost of imports, particularly in energy-dependent economies. Central banks are thus caught in a balancing act, where prioritizing one market often exacerbates risks in the other, making it difficult to maintain stability across both simultaneously.

This is all happening as the same time the U.S. Federal Reserve is nearing a potential interest rate easing cycle, creating a squeeze on yen carry trade investors who face rate increases in Japan and potential rate cuts in the U.S.

One of the ironies associated with the recent volatility ascribed to the Yen carry trade is that we have seen this same thing many times in the recent past. The 2008 global financial crisis offers a stark example of carry trade failure. At the time, Yen carry trades funded investments in higher-yielding assets worldwide. When risk aversion surged, investors unwound their positions, leading to a sharp yen appreciation and widespread losses.

Similarly, the Swiss National Bank’s abandonment of its euro currency peg in 2015 resulted in significant losses for those engaged in Swiss franc carry trades, as the franc appreciated by up to 30% overnight.

Iceland’s experience in 2008 is another reminder of the dangers of carry trades. Investors borrowed in low-interest currencies, like the yen, to invest in Icelandic assets. When the financial crisis hit, Iceland’s currency collapsed, leading to the implosion of its banking sector and a severe economic recession.

The Yen carry trade crisis of August 2024 is likely far from over. With the BoJ continuing to raise rates while global monetary policy diverges, the potential for further market disruptions remains high. As interest rate differentials shift between Japan and other economies, particularly the U.S., central banks are left with limited policy options.

The choice between protecting a nation’s currency or its bond market becomes increasingly difficult, and the volatility in global financial markets may continue to escalate as a result.

Investors and policymakers alike must understand the dynamics associated with carry trades as the turbulence associated with them can strike out of nowhere, and there is nothing to indicate these risks have been fully removed from the global landscape.

Background

The Japanese Economy and the Challenges facing the Bank of Japan

Japan has been grappling with economic stagnation and deflation since the early 1990s, following the bursting of its asset price bubble.

The "lost decades" that ensued were characterized by sluggish economic growth, persistently low (negative) inflation, and a declining population. These challenges led the Bank of Japan (BoJ) to adopt a series of unconventional monetary policies in an effort to revive the economy.

The BoJ's strategy included maintaining near-zero interest rates and engaging in large-scale asset purchases (quantitative easing) to inject liquidity into the financial system and stimulate economic activity.

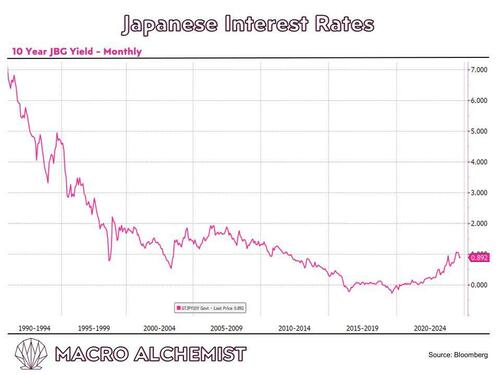

Despite these efforts, Japan struggled to achieve its inflation target of 2%, with inflation remaining stubbornly low or even negative for extended periods. This prolonged period of deflationary pressure led to the introduction of yield curve control (YCC) in 2016, a policy aimed at keeping long-term interest rates low by capping the yield on 10-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs) at around 0%.

Yield Curve Control and Its Implications

Yield curve control was designed to anchor borrowing costs across the Japanese economy, encouraging investment and spending. By keeping long-term rates low, the BoJ aimed to stimulate economic growth and push inflation closer to its target. However, this policy also had significant implications for Japan's financial system and its currency.

Under YCC, the BoJ became the dominant buyer of JGBs, amassing a substantial portion of the market (around 50% of all issuances) and effectively controlling long-term interest rates. While this helped to keep borrowing costs low, it also meant that Japan's interest rates remained exceptionally low compared to those in other developed economies, especially as global economic conditions began to change.

Global Monetary Tightening and the Interest Rate Differential

The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent recovery period led to a dramatic shift in global monetary policy.

As economies reopened and demand surged, inflationary pressures mounted worldwide. Supply chain shocks and bottlenecks, in addition to increasing trade tensions between the US and China also compounded inflation pressures in the COVID aftermath.

In the United States and Europe, inflation reached multi-decade highs, driven by supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and rising energy prices. In response, central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) began to tighten monetary policy aggressively.

The Federal Reserve in particular embarked on a series of rapid interest rate hikes to combat inflation, moving away from the ultra-loose policies that had characterized the previous decade.

This tightening created a significant interest rate differential between Japan and other major economies, particularly the United States. As U.S. interest rates rose, the yield on U.S. assets became increasingly attractive to global investors compared to the near-zero yields on Japanese assets.

This shift in investor preference put downward pressure on the yen, as capital flowed out of Japan and into higher-yielding U.S. assets.

The Global Energy Crisis and Trade Imbalances

The yen's decline was further exacerbated by the global energy crisis that unfolded in 2022. Russia's invasion of Ukraine in February of that year sent shockwaves through global energy markets, driving up the prices of oil, natural gas, and other commodities.

Japan, as one of the world’s largest importers of energy, was particularly vulnerable to these price increases. The cost of importing energy soared, leading to a sharp deterioration in Japan's trade balance.

A widening trade deficit typically weakens a country's currency, as more of the currency is sold to pay for imports than is bought by foreign buyers of exports. In Japan's case, the situation was compounded by the already declining yen, which made energy imports even more expensive in yen terms.

This created a vicious cycle where the weak yen increased the cost of imports, further exacerbating the trade deficit, putting additional downward pressure on the currency and increasing domestic inflation pressures.

Speculative Pressure and Market Dynamics

As the yen continued to weaken, it attracted the attention of currency speculators. Speculative trading, driven by the expectation that the yen would continue to fall, intensified the currency's decline. Traders, betting on further depreciation, engaged in short selling the yen, which added to the selling pressure.

This speculative activity amplified the yen's decline, making it one of the worst-performing major currencies during this period.

The yen's weakness became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, as each round of selling led to more traders jumping on the bandwagon, expecting further declines. The speculative pressure also highlighted the vulnerability of currencies that are perceived to be out of sync with global monetary trends, especially when central banks are seen as committed to policies that diverge from global norms.

Government and Central Bank Responses

Faced with the yen's rapid depreciation and its potential negative impact on the economy, the Japanese government and the BOJ were compelled to take action. Initially, the response involved verbal interventions, with top officials, including Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki, expressing concern about the yen's volatility and warning that excessive weakness could harm the economy.

These statements were intended to signal to the markets that the government was closely monitoring the situation and was prepared to act if necessary.

However, as the yen continued to fall, verbal interventions proved insufficient.

In September 2022, Japan intervened directly in the foreign exchange markets by selling U.S. dollars and buying yen, marking its first intervention in the currency markets since the Asian Financial Crisis of 1998.

The intervention was aimed at stabilizing the yen and curbing its rapid decline. While the intervention provided a temporary boost to the yen, it was not enough to reverse the broader trend, as the fundamental factors driving the yen's weakness—such as the interest rate differential and the trade deficit—remained in place.

The BoJ, meanwhile, maintained its ultra-loose monetary policy despite growing pressure to adjust its approach. Then-BoJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda emphasized the need to support Japan's economic recovery and argued that tightening policy prematurely could derail progress toward the bank's inflation target.

This stance was based on the view that Japan's inflation, which was primarily driven by external factors like energy prices, would not be sustained without stronger domestic demand. The BoJ’s commitment to its existing policy framework, despite the yen's decline, underscored the challenges of balancing domestic economic priorities with the realities of a rapidly changing global financial environment.

Impact on the Japanese Economy

The yen crisis had mixed effects on the Japanese economy. On the one hand, the weaker yen benefited Japan's export-oriented industries by making Japanese goods more competitive in international markets.

Major exporters, such as Toyota, Sony, and other manufacturers, saw their profits increase as they earned more yen per unit of foreign currency. This helped boost corporate earnings and supported Japan’s stock market.

On the other hand, the weaker yen significantly increased the cost of imports, particularly energy and raw materials. This contributed to rising input costs for Japanese businesses, squeezing profit margins for companies that relied on imported goods. For consumers, the weaker yen led to higher prices for imported products, contributing to a rise in consumer inflation.

While inflation remained below the BoJ’s 2% target, the cost-push nature of the inflation - driven by higher import costs rather than strong domestic demand - raised concerns about the sustainability of price increases and the impact on household purchasing power.

The yen crisis of August 2024 was years in the making and has several long-term implications for Japan and the global financial system. It has highlighted the imbalances that can build up in a world of ultra-low (and even negative) interest rates combined with a global marketplace.

The crisis also underscored the challenges of managing a currency in an environment of divergent monetary policies and global financial volatility. It also serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of financial markets and the potential for currency volatility to spill over into other areas of the economy.

There have been many other examples of “carry crises”, where there is an underlying implicit assumption that currency valuations will remain constant. Indeed, almost invariably, currency movements have been seismic at the very times that they were widely expected to be most stable.

It is also important to note that all other things being equal, currency hedging costs tend to eat up the respective differences between currencies. This typically removes any advantages of currency hedging, making all such carry trades completely vulnerable to such tectonic shifts.

In that context, it is worth examining historical examples and consequences of such carry trades.

Continue reading at the Macro Alchemist.

Submitted by Brent Johnson and Michael Peregrine of Santiago Capital.

Executive Summary

Currency carry trades, while seemingly straightforward, carry significant risks due to their reliance on interest rate differentials between countries. Investors borrow in a low-interest currency, like the yen, to invest in higher-yielding assets.

These trades are often unhedged and leveraged, magnifying potential profits but also exposing investors to substantial risks, especially if interest rates or currency values shift unexpectedly. The biggest risk is the implicit assumption that these differentials will remain stable, which rarely holds true over the long term.

Historically, even fixed currency pegs, such as those attempted by the Swiss National Bank and the Bank of England, have failed due to unsustainable capital flows. Despite the lessons learned from past failures, such as when the U.S. decoupled the dollar from the gold standard in 1971, investors are often lured by the allure of stable, easy returns from carry trades.

However, carry trades can appear benign for years before unraveling catastrophically, leading to sudden and severe market volatility. This was the case in the recent yen carry trade crisis of August 2024.

The BoJ now faces a dilemma: Do they protect the Yen with higher interest rates? Or protect the Japanese government bond market with lower rates.

They cannot do both.

This is because the tools used to protect their currency conflict with the tools used to protect the bond market. And vice versa.

To protect a currency, A central bank will typically raise interest rates to make the currency more attractive to investors, which can help stabilize or increase its value. However, higher interest rates increase borrowing costs, leading to lower bond prices and rising yields, which can destabilize the bond market. This dynamic creates a policy dilemma, particularly in economies heavily reliant on debt, as higher yields can hurt economic growth and raise concerns about government debt sustainability.

On the other hand, protecting the bond market requires central banks to keep interest rates low, which supports bond prices and keeps borrowing costs manageable for governments and businesses. However, lower interest rates tend to weaken a currency by making it less attractive to investors seeking higher returns. A weaker currency can fuel inflation by increasing the cost of imports, particularly in energy-dependent economies. Central banks are thus caught in a balancing act, where prioritizing one market often exacerbates risks in the other, making it difficult to maintain stability across both simultaneously.

This is all happening as the same time the U.S. Federal Reserve is nearing a potential interest rate easing cycle, creating a squeeze on yen carry trade investors who face rate increases in Japan and potential rate cuts in the U.S.

One of the ironies associated with the recent volatility ascribed to the Yen carry trade is that we have seen this same thing many times in the recent past. The 2008 global financial crisis offers a stark example of carry trade failure. At the time, Yen carry trades funded investments in higher-yielding assets worldwide. When risk aversion surged, investors unwound their positions, leading to a sharp yen appreciation and widespread losses.

Similarly, the Swiss National Bank’s abandonment of its euro currency peg in 2015 resulted in significant losses for those engaged in Swiss franc carry trades, as the franc appreciated by up to 30% overnight.

Iceland’s experience in 2008 is another reminder of the dangers of carry trades. Investors borrowed in low-interest currencies, like the yen, to invest in Icelandic assets. When the financial crisis hit, Iceland’s currency collapsed, leading to the implosion of its banking sector and a severe economic recession.

The Yen carry trade crisis of August 2024 is likely far from over. With the BoJ continuing to raise rates while global monetary policy diverges, the potential for further market disruptions remains high. As interest rate differentials shift between Japan and other economies, particularly the U.S., central banks are left with limited policy options.

The choice between protecting a nation’s currency or its bond market becomes increasingly difficult, and the volatility in global financial markets may continue to escalate as a result.

Investors and policymakers alike must understand the dynamics associated with carry trades as the turbulence associated with them can strike out of nowhere, and there is nothing to indicate these risks have been fully removed from the global landscape.

Background

The Japanese Economy and the Challenges facing the Bank of Japan

Japan has been grappling with economic stagnation and deflation since the early 1990s, following the bursting of its asset price bubble.

The “lost decades” that ensued were characterized by sluggish economic growth, persistently low (negative) inflation, and a declining population. These challenges led the Bank of Japan (BoJ) to adopt a series of unconventional monetary policies in an effort to revive the economy.

The BoJ’s strategy included maintaining near-zero interest rates and engaging in large-scale asset purchases (quantitative easing) to inject liquidity into the financial system and stimulate economic activity.

Despite these efforts, Japan struggled to achieve its inflation target of 2%, with inflation remaining stubbornly low or even negative for extended periods. This prolonged period of deflationary pressure led to the introduction of yield curve control (YCC) in 2016, a policy aimed at keeping long-term interest rates low by capping the yield on 10-year Japanese government bonds (JGBs) at around 0%.

Yield Curve Control and Its Implications

Yield curve control was designed to anchor borrowing costs across the Japanese economy, encouraging investment and spending. By keeping long-term rates low, the BoJ aimed to stimulate economic growth and push inflation closer to its target. However, this policy also had significant implications for Japan’s financial system and its currency.

Under YCC, the BoJ became the dominant buyer of JGBs, amassing a substantial portion of the market (around 50% of all issuances) and effectively controlling long-term interest rates. While this helped to keep borrowing costs low, it also meant that Japan’s interest rates remained exceptionally low compared to those in other developed economies, especially as global economic conditions began to change.

Global Monetary Tightening and the Interest Rate Differential

The COVID-19 pandemic and the subsequent recovery period led to a dramatic shift in global monetary policy.

As economies reopened and demand surged, inflationary pressures mounted worldwide. Supply chain shocks and bottlenecks, in addition to increasing trade tensions between the US and China also compounded inflation pressures in the COVID aftermath.

In the United States and Europe, inflation reached multi-decade highs, driven by supply chain disruptions, labor shortages, and rising energy prices. In response, central banks like the U.S. Federal Reserve and the European Central Bank (ECB) began to tighten monetary policy aggressively.

The Federal Reserve in particular embarked on a series of rapid interest rate hikes to combat inflation, moving away from the ultra-loose policies that had characterized the previous decade.

This tightening created a significant interest rate differential between Japan and other major economies, particularly the United States. As U.S. interest rates rose, the yield on U.S. assets became increasingly attractive to global investors compared to the near-zero yields on Japanese assets.

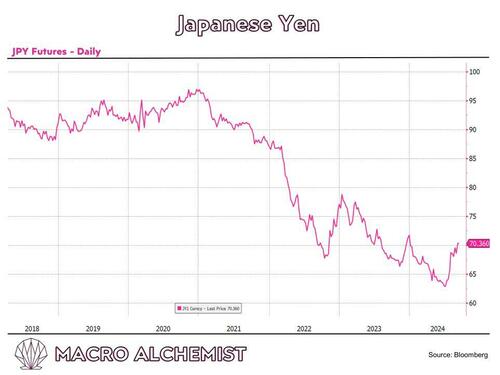

This shift in investor preference put downward pressure on the yen, as capital flowed out of Japan and into higher-yielding U.S. assets.

The Global Energy Crisis and Trade Imbalances

The yen’s decline was further exacerbated by the global energy crisis that unfolded in 2022. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February of that year sent shockwaves through global energy markets, driving up the prices of oil, natural gas, and other commodities.

Japan, as one of the world’s largest importers of energy, was particularly vulnerable to these price increases. The cost of importing energy soared, leading to a sharp deterioration in Japan’s trade balance.

A widening trade deficit typically weakens a country’s currency, as more of the currency is sold to pay for imports than is bought by foreign buyers of exports. In Japan’s case, the situation was compounded by the already declining yen, which made energy imports even more expensive in yen terms.

This created a vicious cycle where the weak yen increased the cost of imports, further exacerbating the trade deficit, putting additional downward pressure on the currency and increasing domestic inflation pressures.

Speculative Pressure and Market Dynamics

As the yen continued to weaken, it attracted the attention of currency speculators. Speculative trading, driven by the expectation that the yen would continue to fall, intensified the currency’s decline. Traders, betting on further depreciation, engaged in short selling the yen, which added to the selling pressure.

This speculative activity amplified the yen’s decline, making it one of the worst-performing major currencies during this period.

The yen’s weakness became something of a self-fulfilling prophecy, as each round of selling led to more traders jumping on the bandwagon, expecting further declines. The speculative pressure also highlighted the vulnerability of currencies that are perceived to be out of sync with global monetary trends, especially when central banks are seen as committed to policies that diverge from global norms.

Government and Central Bank Responses

Faced with the yen’s rapid depreciation and its potential negative impact on the economy, the Japanese government and the BOJ were compelled to take action. Initially, the response involved verbal interventions, with top officials, including Finance Minister Shunichi Suzuki, expressing concern about the yen’s volatility and warning that excessive weakness could harm the economy.

These statements were intended to signal to the markets that the government was closely monitoring the situation and was prepared to act if necessary.

However, as the yen continued to fall, verbal interventions proved insufficient.

In September 2022, Japan intervened directly in the foreign exchange markets by selling U.S. dollars and buying yen, marking its first intervention in the currency markets since the Asian Financial Crisis of 1998.

The intervention was aimed at stabilizing the yen and curbing its rapid decline. While the intervention provided a temporary boost to the yen, it was not enough to reverse the broader trend, as the fundamental factors driving the yen’s weakness—such as the interest rate differential and the trade deficit—remained in place.

The BoJ, meanwhile, maintained its ultra-loose monetary policy despite growing pressure to adjust its approach. Then-BoJ Governor Haruhiko Kuroda emphasized the need to support Japan’s economic recovery and argued that tightening policy prematurely could derail progress toward the bank’s inflation target.

This stance was based on the view that Japan’s inflation, which was primarily driven by external factors like energy prices, would not be sustained without stronger domestic demand. The BoJ’s commitment to its existing policy framework, despite the yen’s decline, underscored the challenges of balancing domestic economic priorities with the realities of a rapidly changing global financial environment.

Impact on the Japanese Economy

The yen crisis had mixed effects on the Japanese economy. On the one hand, the weaker yen benefited Japan’s export-oriented industries by making Japanese goods more competitive in international markets.

Major exporters, such as Toyota, Sony, and other manufacturers, saw their profits increase as they earned more yen per unit of foreign currency. This helped boost corporate earnings and supported Japan’s stock market.

On the other hand, the weaker yen significantly increased the cost of imports, particularly energy and raw materials. This contributed to rising input costs for Japanese businesses, squeezing profit margins for companies that relied on imported goods. For consumers, the weaker yen led to higher prices for imported products, contributing to a rise in consumer inflation.

While inflation remained below the BoJ’s 2% target, the cost-push nature of the inflation – driven by higher import costs rather than strong domestic demand – raised concerns about the sustainability of price increases and the impact on household purchasing power.

The yen crisis of August 2024 was years in the making and has several long-term implications for Japan and the global financial system. It has highlighted the imbalances that can build up in a world of ultra-low (and even negative) interest rates combined with a global marketplace.

The crisis also underscored the challenges of managing a currency in an environment of divergent monetary policies and global financial volatility. It also serves as a reminder of the interconnectedness of financial markets and the potential for currency volatility to spill over into other areas of the economy.

There have been many other examples of “carry crises”, where there is an underlying implicit assumption that currency valuations will remain constant. Indeed, almost invariably, currency movements have been seismic at the very times that they were widely expected to be most stable.

It is also important to note that all other things being equal, currency hedging costs tend to eat up the respective differences between currencies. This typically removes any advantages of currency hedging, making all such carry trades completely vulnerable to such tectonic shifts.

In that context, it is worth examining historical examples and consequences of such carry trades.

Continue reading at the Macro Alchemist.

Loading…