–>

June 1, 2022

What a world of difference there is between anti-Islamic polemics emanating from the secular West and those emanating from the religiously charged Arab world itself. This is the thought I have whenever I watch Arabic-language programs and debates, which tend to have an unrestrained and animated quality.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

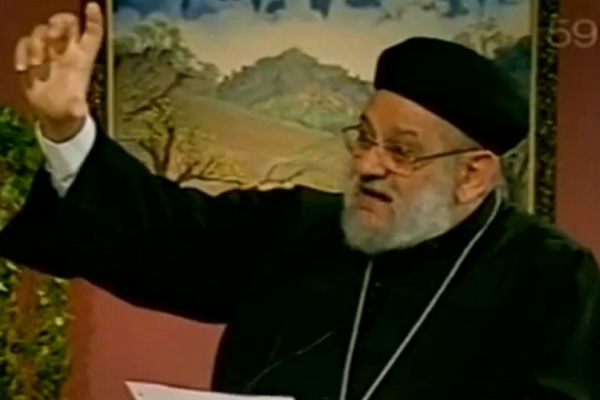

Fr. Zakaria Botros, first introduced to non-Arabic-speakers in this 2008 article, is an especially appropriate case study. Originally a Coptic Christian priest from Egypt turned polemicist and evangelist, since around 2000, he has become a major thorn in Islam’s side, as evidenced by the many calls for his assassination.

Zakaria appears on a satellite channel, al-Fady TV, where he regularly takes Islam to task, primarily by asking tough questions concerning many of its most authoritative texts (Koran, hadith, sira, tafsirs, etc.) and teachings. And I don’t mean the tough questions that we’re familiar with — for example, if Islam is a religion of peace, why is the Koran inundated with violence and intolerance? No, he has dug into even the most arcane of Islam’s books (almost all of which have not been translated out of Arabic) and unearthed some immensely problematic revelations.

A recent episode, for example, revolved around a bizarre hadith recorded in several respected Islamic texts, including the hadith collections of Ibn Hanbal, a founder of one of Islam’s four Sunni madhhabs. In it, Muhammad takes a companion, Abdullah bin Mas’ud, out into the desert night. The prophet then draws a circle in the sand and tells ibn Mas’ud not to leave it. Muhammad then goes off a little distance, at which point his companion and narrator of the hadith, says he saw two tall, naked men appear and go to Muhammad, whereupon “they began to ride [يركبون, which can also be translated as mount] the Messenger of Allah.” Meanwhile, and all through the night, these strange men would also try to access Mas’ud, who records being “terrified,” though they were prevented from crossing the circle made by Muhammad. Then, with the rising of the sun, they quickly absconded, whereupon Mas’ud saw Muhammad approaching him, “slowly and in pain from being ridden.” The unflattering implications were then elaborated by Fr. Zakaria.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Another episode revolved around the recent slaughter of a fellow Coptic Christian priest in Egypt, Fr. Arsenious Wadid. In it, Fr. Zakaria sought to expose the “true terrorist” behind this crime. It wasn’t the actual Muslim murderer, he said, nor even Muhammad himself, but rather “the Lord of Muhammad — that is, Satan!” Thereafter, he examined Koran verse after Koran verse — dealing with deceiving, killing, plundering, and sexually enslaving women — as proof of a diabolical rather than heavenly inspiration. As is his wont, he complemented his presentation by quoting Christian scriptures; for example, he said John 8:44 was a foretelling of Allah and those he would deceive:

You belong to your father, the devil, and you want to carry out your father’s desires. He was a murderer from the beginning, not holding to the truth, for there is no truth in him. When he lies, he speaks his native language, for he is a liar and the father of lies.

Although this quick summation of episodes risks presenting them as consisting of vindictive and undocumented slanders against Islam and its prophet, in reality, during the bulk of his hour-long episodes, including the aforementioned two, Fr. Zakaria offers copious documentation: he relies almost exclusively on well respected and authoritative Muslim sources, from al-turath al-Islami (the Islamic heritage). He methodically provides complete references to all the texts he uses; shows images of the text itself, including page number; and, finally, challenges any and all experts in Islam to call in and correct him if he’s wrong.

Such is the dilemma Muslims face: because his shows, which now number in the thousands, are entirely in Arabic and, for some two decades, have been aired via satellite and on the internet, millions of Muslims have been exposed to his relentless onslaught against their religion and their prophet — even as the guardians of their faith, the ulema, offer little in response but ad hominem dismissals and calls for his death for insulting Muhammad. (As discussed here, one prominent sheikh, while being pressed by a talk show host to offer an answer to one of Fr. Zakaria’s many accusations against Islam, responded by yelling at the host and storming off set on live television.)

The latest strategy for dealing with Fr. Zakaria appears to be for Muslims collectively to pretend he doesn’t exist. Anyone who ever raises his name during a televised show is immediately attacked for daring to name such a “despicable” personage. Even so, the quiet, ongoing efficacy of his mission is discernible, as evidenced by the frequent callers who tell him they were once Muslims who wished only to see his head on a platter, but that, through the years, they’ve come to embrace Christianity.

This leads to perhaps the most effective aspect of Fr. Zakaria’s ministry to Muslims: he speaks their language, in more ways than one. Unlike most Western critics, he doesn’t critique Islam from a secular point of view — by arguing, for example, that Islam is not conducive to “human rights” or “gender equality,” concepts that have zero resonance with Muslims and can never supplant their more fundamental yearnings. Nor does he behave as many Western Christians, never once criticizing Islam, but rather hoping to build “ecumenical” bridges with Muslims concerning “shared commonalities,” an approach well typified by Pope Francis and his ilk. As for those very few Western Christian critics who do approach Islam boldly, they unfortunately lack the language skills to have any impact on or even be recognized by the Muslim world — not least because they cannot access the many untranslated Arabic texts of Islam’s long heritage, where so many of its lesser known but equally potent weaknesses lie.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

And so Fr. Zakaria appears to maintain his original mantle: that of a Christian evangelist boldly declaring the Gospel truth in order to save as many Muslim souls from, as he puts it, “the clutches of Satan/Allah.” To that end, he has produced as many if not more episodes that have nothing to do with Islam and everything to do with bringing Muslims to Christ.

A final ingredient behind his efficacy is, ironically, what no doubt turns off many in the West: he approaches his topic the same way Muslims do — with passion, unrestrained and unfiltered, holding no punches, with not a little sarcasm if not outright ridicule. In his recent episode asserting that Allah is Satan, for example, he sincerely and passionately yelled at his viewers: “When will you wake up to the truth?! Stop being fools! … Islam is a cancer in your bodies that must be removed before it’s too late!” That Fr. Zakaria is currently 87 years old and still going strong only adds to the effect.

It is due to all of these factors — that Fr. Zakaria speaks their language (literally and figuratively); that he has an expert knowledge of and regularly exposes Islam’s most esoteric Arabic texts and teachings; that the guardians of Islam are unable to respond to him, aside from name-calling and death threats; that he articulates his arguments through not a secular, but rather a religious paradigm; and that he offers Muslims a real alternative to Islam (Christianity, as opposed to default Western paradigms of humanism or materialism) — it is due to all of this that I think Zakaria Botros is having a profound impact on the Muslim world.

Nor, I should add, is he alone. While this article has focused on Fr. Zakaria Botros, not least because he’s one of the first to pioneer this method of reaching out to Muslims — thanks first to the satellite and then to the internet — he is hardly alone. In recent years, many others, including Muslim converts to Christianity — Brother Rachid being most prominent among them — have taken a similar approach on their television programs: presenting, questioning, and criticizing strange and problematic aspects of Islam, all of which are based on Islam’s own texts.

Such, then, is one of the most effective approaches to Islam — one that is naturally being missed by the West, in part because of the language barrier, but more because the West, much like the Muslim world, rejects such an “abrasive,” “disrespectful,” and ultimately “overly Christian” approach to Islam.

Raymond Ibrahim, author of the new book Defenders of the West: The Christian Heroes Who Stood Against Islam, is a Shillman Fellow at the David Horowitz Freedom Center, a Judith Rosen Friedman Fellow at the Middle East Forum, and a Distinguished Senior Fellow at the Gatestone Institute.

Image: MrSuduvis via YouTube.

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>