–>

April 13, 2023

Thomas Jefferson owned slaves and is widely believed by able and honorable people to have raped the enslaved child Sally Hemings and fathered all her children. Therefore, it’s understandable that some wish to see our third president “canceled,” to use the Woke vernacular.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

Today would be Jefferson’s 280th birthday, so it seems fitting to pause briefly and reassess these horrendous allegations. I have studied Thomas Jefferson for more than half a century, and I am delighted to report that his critics are misinformed.

In reality, Thomas Jefferson may well have been America’s first abolitionist. Moreover, by far the most thorough investigation of the alleged Jefferson-Hemings sexual relationship—a year-long inquiry involving more than a dozen senior professors from all over the country—concluded (with but a single mild dissent) that the allegation is false.

Jefferson’s critics are not wrong about everything. He did own slaves, and (to use his language) slavery was certainly “an abomination.” But when he inherited slaves upon the deaths of his father and father-in-law, it was illegal in Virginia to free them. And it was Thomas Jefferson who, in 1769, drafted the law that permitted manumitting slaves and, later, the 1778 law prohibiting importing new slaves into Virginia.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

The first of these laws led Marxist Professor Philip Foner—who edited a book of Jefferson’s writings, a two-volume collection of The Complete Writings of Thomas Paine, and a five-volume collection of the writings of abolitionist Frederick Douglass—to identify Jefferson (rather than Paine) as America’s “first abolitionist.”

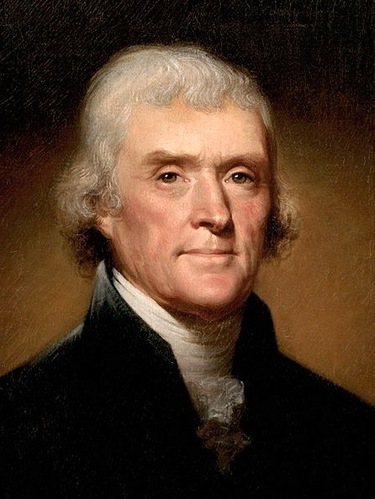

Image: Thomas Jefferson by Rembrandt Peale.

In his original draft of the Declaration of Independence, Jefferson denounced King George III for having “waged cruel war against human nature itself” on “a distant people who never offended him” by “carrying them into slavery in another hemisphere.” Most Americans today don’t know this, because the language was removed to keep Georgia and South Carolina from walking out of the convention.

Addressing slavery in his only book, Notes on the State of Virginia (1783), Jefferson reasoned,

[C]an the liberties of a nation be thought secure when we have removed their only firm basis, a conviction in the minds of the people that these liberties are of the gift of God? That they are not to be violated but with his wrath? Indeed I tremble for my country when I reflect that God is just: that his justice cannot sleep for ever…. The Almighty has no attribute which can take side with us in such a contest.

Article 1, section 9, of the Constitution, prohibited Congress from banning the slave trade for two decades. More than a year before that period elapsed, President Jefferson congratulated Congress on its approaching “opportunity to withdraw the citizens of the United States from all further participation in those violations of human rights which have been so long continued on the unoffending inhabitants of Africa, and which the morality, the reputation, and the best interests of our country, have long been eager to proscribe.” Congress concurred at the earliest opportunity.

As a member of the Second Continental Congress in 1784, Jefferson was called upon to draft rules to govern the Northwest Territories. Article Six read: “There shall be neither slavery nor involuntary servitude in the said territory, otherwise than in the punishment of crimes whereof the party shall have been duly convicted.” It failed by one vote, leading Jefferson to lament, “heaven was silent in that awful moment!” But seven decades later, near the end of the Civil War, the authors of the Thirteenth Amendment incorporated Jefferson’s language to honor his courageous struggle against slavery.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

I have in the past described Jefferson as a “reluctant racist,” because he did express the “tentative” view that African slaves were not as intelligent as other races (while giving blacks the nod in such areas as physical courage and musical talent). But he was certainly not a “white supremacist,” having argued in 1785 that Native Americans were in body and mind “equal to the white man.” The following year, he wrote, “The want of attention to their rights is a principal source of dishonor to the American character.” Many were also offended by Jefferson’s defense of the rights of Jews and Muslims.

Days before concluding his second term as president, Jefferson wrote, in a February 25, 1809, letter to Henri Grégoire, that no person would be more pleased than himself to see refuted the doubts he had expressed about the intellectual abilities of black slaves—a distinction he repeatedly emphasized might be but a consequence of their enslaved circumstances. He added, “[W]hatever be their degree of talent, it is no measure of their rights. Because Sir Isaac Newton was superior to others in understanding, he was not therefore lord of the person or property of others.”

In American Sphinx, Professor Joseph Ellis asserted Jefferson could have passed a polygraph test confirming his conviction that his own slaves “were more content and better off as members of his extended family than under any other imaginable circumstances.” This view was reinforced when Jefferson manumitted the highly talented James Hemings in 1796, after which James soon turned to alcohol and committed suicide. Jefferson died deeply in debt in 1826, and Section 54 of the Revised Virginia Code of 1819 made it illegal to free slaves (like livestock, legally considered chattel property) until all an estate’s creditors were satisfied.

In 2000-2001, I chaired the above-mentioned Jefferson-Hemings Scholars Commission, which included professors who had taught at Harvard, Yale, Oxford, Brown, UVA, and several other prestigious universities. After an intensive, year-long study, we concluded (with one mild dissent) that the charge that Thomas Jefferson fathered even one child by the enslaved Ms. Hemings is likely false.

The 1998 DNA study reported in the science journal Nature as having established Thomas Jefferson’s paternity of Sally Hemings’ youngest son Eston did not even have a sample of Thomas Jefferson’s DNA to test. Dr. Eugene Foster, who designed and oversaw the study, emphasized that the results pointed equally to any of the more than two-dozen adult Jefferson males known to have been in Virginia at the time. Based entirely upon the DNA evidence, the odds that Thomas Jefferson fathered Eston are under 5%.

For many generations, Eston’s descendants passed down the story that he was not President Jefferson’s child but the son of an “uncle.” President Jefferson’s much younger brother Randolph was known at Monticello as “Uncle Randolph” because of his relationship to the president’s daughter Martha, who ran the plantation when her father was in the White House.

Roughly 15 days before Eston’s most likely conception date, Randolph was invited to visit Monticello to see his beloved twin sister, who had returned from an extended absence. Randolph had five sons between the ages of 14 and 27 who would likely have accompanied him and would be more likely suspects than the 64-year-old President. The book Memoirs of a Monticello Slave notes that, when Randolph visited Monticello, he would “come out among black people, play his fiddle, and dance half the night.”

Our 400-page report is available on-line for anyone to read. Numerous efforts to arrange a debate have failed because no pro-paternity scholar has been willing to take part. The offer remains open.

Professor Turner retired from the University of Virginia in 2020 and is writing a book on Jefferson and Slavery. The Scholars Commission report can be found here.

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>