Late last week, we were the first to correctly summarize what the bottom line of the so-called "debt ceiling deal" meant for the US, for future generations of Americans, and for the ridiculous melodrama gripping Washington: a -0.2% of GDP cut in nominal spending.

Hey @mattgaetz, the debt ceiling deal "cuts" spending by 0.2% of GDP or about $50 billion.

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) May 28, 2023

Is that good enough?

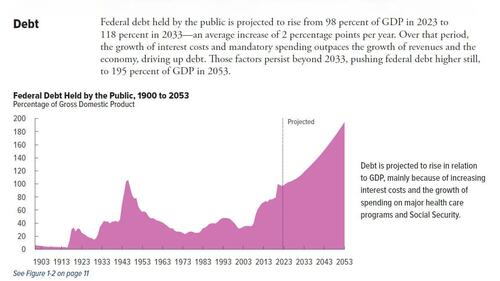

That's right: that 0.2% cut in spending is what all the brewhaha was over, a cut which will not only push total debt to $35 trillion by the end of Biden's term, but will not even put a dent in the long-term US debt trajectory which even the CBO has no problem as showing in its full, hyperinflationary glory.

Still, to Kevin McCarthy who "negotiated" on behalf of America's conservatives, that paltry, laughable nominal "spending reduction" was apparently something to be very proud of, as he repeatedly pointed out on his twitter feed...

It is simple:

— Kevin McCarthy (@SpeakerMcCarthy) May 29, 2023

- President Biden wanted to spend more and raise taxes.

- Republicans fought—and won—to reduce spending and stop Biden from radical overreach.

The systemic reforms we set in place mark the beginning of historic change in Washington. https://t.co/rjMNsSf5oX

... if only a closer look reveals that not all is as it seems.

In its post-mortem of the debt ceiling deal published this evening, Goldman summarizes the outcome as follows: "the spending deal looks likely to reduce spending by 0.1-0.2% of GDP yoy in 2024 and 2025, compared with a baseline in which funding grows with inflation. That said, the boost to funding Congress approved late last year for FY23 was so large (nearly 10% yoy) that overall discretionary spending is likely to be slightly higher in real terms next year despite the new caps."

Translation: the "deal" may result in a nominal 0.1% drop in spending (just for next year, after that it ramps up again), but adjusted for inflation, spending in 2024 will be higher yet again!

Below we excerpt several highlights from the Goldman note, first focusing on the probability of the deal becoming enacted; according to Goldman, the deal is "very likely to pass both chambers of Congress in the coming week" although there are two points of uncertainty in the House.

- First, the Rules Committee will meet to vote Tuesday (May 30) afternoon/evening on the rule for debate on the debt limit bill, a necessary step before the vote on the House floor. The committee has 9 Republicans and 4 Democrats, but 2 of those Republicans (Reps. Roy and Norman) appear to oppose the bill, with the position of a third (Rep. Massie) unclear. If all three vote against and no Democrat votes in favor, the bill will fail. (Goldman thinks the Rules Committee is very likely to send the bill on to the House Floor, as a majority of the committee will vote for the package even if it takes Democratic support - it is uncommon but not unheard-of for the minority party to support the majority party's efforts in the Rules Committee).

- Assuming Rules Committee passage on Tuesday, the House is likely to vote late on Wednesday (May 31). While it is not entirely clear how Republican and Democratic lawmakers will divide the responsibility for passing this legislation–most lawmakers likely want it to pass but few want to vote for it. As such Goldman is confident that a failed vote in the House is very unlikely. Assuming the House clears the bill Wednesday, the Senate is unlikely to vote on final passage before Friday (June 2) and procedural delays could easily push the vote into the weekend. That said, there is less uncertainty regarding support in the Senate than there is in the House, so this is more a question of timing than outcome.

... and second, why the so-called spending cuts are a joke:

The main source of budgetary savings in the deal is a two-year cap on federal discretionary spending. Congress appropriates this segment of spending annually and it accounts for around 25% of total federal spending, with slightly more than half dedicated to defense and the remainder to other "non-defense" spending (generally domestic programs outside of the major benefit programs). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) will estimate that the spending caps in the deal will reduce discretionary spending by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years and reduce interest expense by around $160-170bn over that period. On paper, this would reduce projected deficits over the next decade by an average of 0.4-0.5% of GDP.

That said, the actual spending cut will be much smaller, for two reasons.

- First, the caps apply for only two years, so most of the projected savings will depend on policy decisions made after the next election. (The description of the deal states that caps apply for 6 years, but they are only enforceable via sequestration for 2024 and 2025 and should have little effect thereafter.)

- Second, the deal included other details that lessen the effect of the cuts, particularly in 2024. This includes counting the bill's rescissions of unused COVID funding against spending for the coming year, pre-funding certain items so the spending is excluded from the caps, and a side agreement that $20bn in IRS enforcement funding that would have been spent later in the decade will be redirected toward domestic spending without counting toward the cap. With these adjustments, the White House has indicated it believes non-defense spending will be roughly flat in nominal terms in FY24 compared with this year.

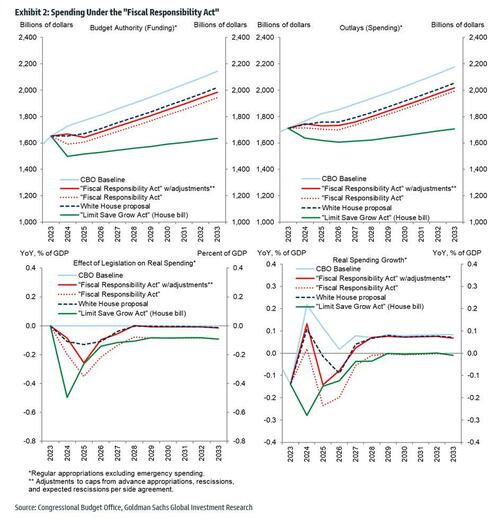

The chart below provides a rough estimates of the effect of the spending caps with and without the adjustments just described, compared with the White House's initial reported offer (a freeze in discretionary spending for FY24, and a 1% increase for FY25) and the Republican bill the House passed in April.

Other things equal, the adjusted caps look likely to reduce spending by 0.1-0.2% of GDP yoy in 2024 and 2025 (lower left chart).

And here is the punchline: because the increase in funding for FY23 that Congress approved late last year was so large (nearly 10% yoy) some of that spending boost will spill over into FY24 and overall spending is likely to be higher in real terms next year despite the new caps (lower right chart).

And just like that the uniparty has sold America down the river yet again.

* * *

More in the full Goldman note available to professional subscribers in the usual place.

Late last week, we were the first to correctly summarize what the bottom line of the so-called “debt ceiling deal” meant for the US, for future generations of Americans, and for the ridiculous melodrama gripping Washington: a -0.2% of GDP cut in nominal spending.

Hey @mattgaetz, the debt ceiling deal “cuts” spending by 0.2% of GDP or about $50 billion.

Is that good enough?

— zerohedge (@zerohedge) May 28, 2023

That’s right: that 0.2% cut in spending is what all the brewhaha was over, a cut which will not only push total debt to $35 trillion by the end of Biden’s term, but will not even put a dent in the long-term US debt trajectory which even the CBO has no problem as showing in its full, hyperinflationary glory.

Still, to Kevin McCarthy who “negotiated” on behalf of America’s conservatives, that paltry, laughable nominal “spending reduction” was apparently something to be very proud of, as he repeatedly pointed out on his twitter feed…

It is simple:

– President Biden wanted to spend more and raise taxes.

– Republicans fought—and won—to reduce spending and stop Biden from radical overreach.The systemic reforms we set in place mark the beginning of historic change in Washington. https://t.co/rjMNsSf5oX

— Kevin McCarthy (@SpeakerMcCarthy) May 29, 2023

… if only a closer look reveals that not all is as it seems.

In its post-mortem of the debt ceiling deal published this evening, Goldman summarizes the outcome as follows: “the spending deal looks likely to reduce spending by 0.1-0.2% of GDP yoy in 2024 and 2025, compared with a baseline in which funding grows with inflation. That said, the boost to funding Congress approved late last year for FY23 was so large (nearly 10% yoy) that overall discretionary spending is likely to be slightly higher in real terms next year despite the new caps.”

Translation: the “deal” may result in a nominal 0.1% drop in spending (just for next year, after that it ramps up again), but adjusted for inflation, spending in 2024 will be higher yet again!

Below we excerpt several highlights from the Goldman note, first focusing on the probability of the deal becoming enacted; according to Goldman, the deal is “very likely to pass both chambers of Congress in the coming week” although there are two points of uncertainty in the House.

- First, the Rules Committee will meet to vote Tuesday (May 30) afternoon/evening on the rule for debate on the debt limit bill, a necessary step before the vote on the House floor. The committee has 9 Republicans and 4 Democrats, but 2 of those Republicans (Reps. Roy and Norman) appear to oppose the bill, with the position of a third (Rep. Massie) unclear. If all three vote against and no Democrat votes in favor, the bill will fail. (Goldman thinks the Rules Committee is very likely to send the bill on to the House Floor, as a majority of the committee will vote for the package even if it takes Democratic support – it is uncommon but not unheard-of for the minority party to support the majority party’s efforts in the Rules Committee).

- Assuming Rules Committee passage on Tuesday, the House is likely to vote late on Wednesday (May 31). While it is not entirely clear how Republican and Democratic lawmakers will divide the responsibility for passing this legislation–most lawmakers likely want it to pass but few want to vote for it. As such Goldman is confident that a failed vote in the House is very unlikely. Assuming the House clears the bill Wednesday, the Senate is unlikely to vote on final passage before Friday (June 2) and procedural delays could easily push the vote into the weekend. That said, there is less uncertainty regarding support in the Senate than there is in the House, so this is more a question of timing than outcome.

… and second, why the so-called spending cuts are a joke:

The main source of budgetary savings in the deal is a two-year cap on federal discretionary spending. Congress appropriates this segment of spending annually and it accounts for around 25% of total federal spending, with slightly more than half dedicated to defense and the remainder to other “non-defense” spending (generally domestic programs outside of the major benefit programs). The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) will estimate that the spending caps in the deal will reduce discretionary spending by $1.5 trillion over the next 10 years and reduce interest expense by around $160-170bn over that period. On paper, this would reduce projected deficits over the next decade by an average of 0.4-0.5% of GDP.

That said, the actual spending cut will be much smaller, for two reasons.

- First, the caps apply for only two years, so most of the projected savings will depend on policy decisions made after the next election. (The description of the deal states that caps apply for 6 years, but they are only enforceable via sequestration for 2024 and 2025 and should have little effect thereafter.)

- Second, the deal included other details that lessen the effect of the cuts, particularly in 2024. This includes counting the bill’s rescissions of unused COVID funding against spending for the coming year, pre-funding certain items so the spending is excluded from the caps, and a side agreement that $20bn in IRS enforcement funding that would have been spent later in the decade will be redirected toward domestic spending without counting toward the cap. With these adjustments, the White House has indicated it believes non-defense spending will be roughly flat in nominal terms in FY24 compared with this year.

The chart below provides a rough estimates of the effect of the spending caps with and without the adjustments just described, compared with the White House’s initial reported offer (a freeze in discretionary spending for FY24, and a 1% increase for FY25) and the Republican bill the House passed in April.

Other things equal, the adjusted caps look likely to reduce spending by 0.1-0.2% of GDP yoy in 2024 and 2025 (lower left chart).

And here is the punchline: because the increase in funding for FY23 that Congress approved late last year was so large (nearly 10% yoy) some of that spending boost will spill over into FY24 and overall spending is likely to be higher in real terms next year despite the new caps (lower right chart).

And just like that the uniparty has sold America down the river yet again.

* * *

More in the full Goldman note available to professional subscribers in the usual place.

Loading…