Below is my column in The Messenger on the Georgia indictment. As expected, the indictment is a sweeping racketeering based prosecution involving former president Donald Trump and the 18 other defendants. The scope of the alleged conspiracy is massive. “The call” is one of those steps but the famous line that has occupied hours of coverage (and led to the investigation) is not the central allegation. Indeed, every call, speech, and tweet appears a criminal step in the conspiracy.

District Attorney Fani Willis appears to have elected to charge everything and everyone and let God sort them out.

Here is the column from yesterday before the release of the indictment:

“Oh Georgia, no peace I find (no peace I find).”

Those lyrics made famous by the late, great Ray Charles could have been written for former president Donald Trump this week as he awaits his expected fourth indictment. The long-anticipated indictment by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis is expected in the coming days and will focus on alleged election tampering and related offenses in the 2020 presidential election.

If indictments were treated like frequent flyer miles, Donald Trump would get the Georgia indictment for free. However, it will be anything but costless. Regardless of the merits, it will magnify both the cost and complications for Trump.

Like the New York indictment, a Georgia indictment would not be subject to a presidential pardon. Not only have GOP candidates indicated that they would pardon Trump on any federal charges if elected to the presidency, Trump could pardon himself (including a preemptive pardon before trial) if elected — but that power does not reach state convictions.

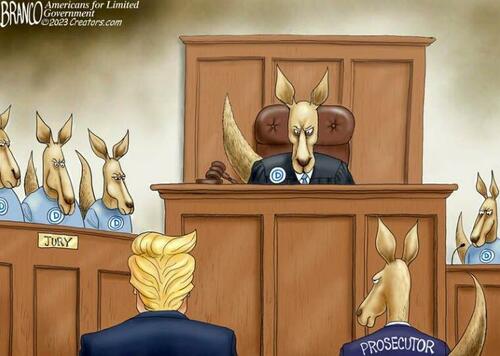

As with Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, many view Willis as a Democratic prosecutor pursuing the highly unpopular former president. However, given the three grand juries and the three years that have passed, Willis may have found new evidence or witnesses that could tie Trump to criminal conduct in seeking to challenge the results in the election.

Thus far, the focus has been on the controversial call that Trump had with Georgia officials — a call widely cited as indisputable evidence of an effort at voting fraud. Yet, the call was similar to a settlement discussion, as state officials and the Trump team hashed out their differences and a Trump demand for a statewide recount. Trump had lost the state by less than 12,000 votes. That might be what he meant when he stated, “I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have because we won the state.”

While others have portrayed the statement as a raw call for fabricating the votes, it seems more likely that Trump was swatting back claims that there was no value to a statewide recount by pointing out that he wouldn’t have to find a statistically high number of votes to change the outcome of the election. It is telling that many politicians and pundits refuse to even acknowledge that obvious alternate meaning.

For Trump’s part, he is not helping with his signature, all-caps social media attacks.

In addition to attacking Willis for a supposedly “racist” and “unethical” past, Trump recently declared that Willis “wants to indict me for a perfect phone call; this was even better than my perfect call on Ukraine.” I have previously disagreed with the claimed perfection of that Ukraine call, the subject of Trump’s first impeachment. However, neither call needs to be “perfect” to be protected.

The importance made of the call in the likely Georgia indictment will be one of the greatest “tells” as to what Willis has in terms of evidence. If the call is a critical linchpin to the prosecution, it will look like a political stunt out of the Bragg-school of prosecution.

There have also been stories indicating that Willis is focusing on connections of Trump team members like Rudy Giuliani to a “breach” of the voting system on Jan. 7, 2021. The team was seeking access to the voting machines to show that they could be compromised or manipulated. Text messages state that the team secured an “invitation” to examine the machines in Coffee County.

That “invitation” was reportedly from a Coffee County elections official, who also reportedly claimed, incorrectly, that votes could be “easily” flipped from Trump to Biden.

Coffee County was also discussed as an example of voting irregularities to justify a proposed draft executive order to seize voting machines. However, that order was never sent out.

The problem is that these messages also apparently refer to “voluntary access” and that may have been what was conveyed to Trump. One message reads: “Most immediately, we were just granted access — by written invitation! — to Coffee County’s systems. Yay!”

Yet, the Coffee County allegations highlight another risk in the Georgia prosecution. There are clearly a number of people beyond Trump who are being targeted, including his lawyers Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell. Indictments can unnerve associates who lack the money or support of Trump. That can lead to flipping key figures to offer state evidence.

The greatest challenge for Georgia is to offer a discernible limiting principle on when challenges in close elections are permissible and when they are criminal. There is a relatively short period between the presidential election in November and counting of electoral votes in January. That means that challenges are often made on incomplete data or unresolved allegations. Generally, candidates are suing election officials who control the machines, data, and other evidence needed to make a case. They often (as they did in 2020) resist demands for access to evidence.

That is not to excuse the claims made by the Trump team. In the coverage after the election, I criticized both sides. I could not understand how many experts were declaring that there was no evidence of voting irregularities a day after the election, before any data were available. However, I also said that the Trump campaign had failed to supply such evidence in critical court filings. I also publicly disagreed with Trump’s fraud claims.

It is important for campaigns to seek judicial review of election challenges without fear of prosecution. Some Democratic lawyers after 2020 made their own controversial (and unsuccessful) allegations of machines flipping or altering election outcomes. No one suggested that they should be criminally charged or disbarred.

The pile-on of prosecutions could create a chilling effect for campaigns in seeking recounts and reviews in close elections. That does not mean that there may not be evidence of knowing fraud or criminal wrongdoing. However, another anemic filing like the one in New York will only fuel the deep political divisions and unrest in the country. It needs to be clearly based on a desire for justice, rather than “just deserts.”

For Trump, of course, he may feel that (as Ray Charles sang) it always seems that “the road leads back to you” for Democratic prosecutors. That itself is not a problem so long as the road is both straight and well laid.

Below is my column in The Messenger on the Georgia indictment. As expected, the indictment is a sweeping racketeering based prosecution involving former president Donald Trump and the 18 other defendants. The scope of the alleged conspiracy is massive. “The call” is one of those steps but the famous line that has occupied hours of coverage (and led to the investigation) is not the central allegation. Indeed, every call, speech, and tweet appears a criminal step in the conspiracy.

District Attorney Fani Willis appears to have elected to charge everything and everyone and let God sort them out.

Here is the column from yesterday before the release of the indictment:

“Oh Georgia, no peace I find (no peace I find).”

Those lyrics made famous by the late, great Ray Charles could have been written for former president Donald Trump this week as he awaits his expected fourth indictment. The long-anticipated indictment by Fulton County District Attorney Fani Willis is expected in the coming days and will focus on alleged election tampering and related offenses in the 2020 presidential election.

If indictments were treated like frequent flyer miles, Donald Trump would get the Georgia indictment for free. However, it will be anything but costless. Regardless of the merits, it will magnify both the cost and complications for Trump.

Like the New York indictment, a Georgia indictment would not be subject to a presidential pardon. Not only have GOP candidates indicated that they would pardon Trump on any federal charges if elected to the presidency, Trump could pardon himself (including a preemptive pardon before trial) if elected — but that power does not reach state convictions.

As with Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg, many view Willis as a Democratic prosecutor pursuing the highly unpopular former president. However, given the three grand juries and the three years that have passed, Willis may have found new evidence or witnesses that could tie Trump to criminal conduct in seeking to challenge the results in the election.

Thus far, the focus has been on the controversial call that Trump had with Georgia officials — a call widely cited as indisputable evidence of an effort at voting fraud. Yet, the call was similar to a settlement discussion, as state officials and the Trump team hashed out their differences and a Trump demand for a statewide recount. Trump had lost the state by less than 12,000 votes. That might be what he meant when he stated, “I just want to find 11,780 votes, which is one more than we have because we won the state.”

While others have portrayed the statement as a raw call for fabricating the votes, it seems more likely that Trump was swatting back claims that there was no value to a statewide recount by pointing out that he wouldn’t have to find a statistically high number of votes to change the outcome of the election. It is telling that many politicians and pundits refuse to even acknowledge that obvious alternate meaning.

For Trump’s part, he is not helping with his signature, all-caps social media attacks.

In addition to attacking Willis for a supposedly “racist” and “unethical” past, Trump recently declared that Willis “wants to indict me for a perfect phone call; this was even better than my perfect call on Ukraine.” I have previously disagreed with the claimed perfection of that Ukraine call, the subject of Trump’s first impeachment. However, neither call needs to be “perfect” to be protected.

The importance made of the call in the likely Georgia indictment will be one of the greatest “tells” as to what Willis has in terms of evidence. If the call is a critical linchpin to the prosecution, it will look like a political stunt out of the Bragg-school of prosecution.

There have also been stories indicating that Willis is focusing on connections of Trump team members like Rudy Giuliani to a “breach” of the voting system on Jan. 7, 2021. The team was seeking access to the voting machines to show that they could be compromised or manipulated. Text messages state that the team secured an “invitation” to examine the machines in Coffee County.

That “invitation” was reportedly from a Coffee County elections official, who also reportedly claimed, incorrectly, that votes could be “easily” flipped from Trump to Biden.

Coffee County was also discussed as an example of voting irregularities to justify a proposed draft executive order to seize voting machines. However, that order was never sent out.

The problem is that these messages also apparently refer to “voluntary access” and that may have been what was conveyed to Trump. One message reads: “Most immediately, we were just granted access — by written invitation! — to Coffee County’s systems. Yay!”

Yet, the Coffee County allegations highlight another risk in the Georgia prosecution. There are clearly a number of people beyond Trump who are being targeted, including his lawyers Rudy Giuliani and Sidney Powell. Indictments can unnerve associates who lack the money or support of Trump. That can lead to flipping key figures to offer state evidence.

The greatest challenge for Georgia is to offer a discernible limiting principle on when challenges in close elections are permissible and when they are criminal. There is a relatively short period between the presidential election in November and counting of electoral votes in January. That means that challenges are often made on incomplete data or unresolved allegations. Generally, candidates are suing election officials who control the machines, data, and other evidence needed to make a case. They often (as they did in 2020) resist demands for access to evidence.

That is not to excuse the claims made by the Trump team. In the coverage after the election, I criticized both sides. I could not understand how many experts were declaring that there was no evidence of voting irregularities a day after the election, before any data were available. However, I also said that the Trump campaign had failed to supply such evidence in critical court filings. I also publicly disagreed with Trump’s fraud claims.

It is important for campaigns to seek judicial review of election challenges without fear of prosecution. Some Democratic lawyers after 2020 made their own controversial (and unsuccessful) allegations of machines flipping or altering election outcomes. No one suggested that they should be criminally charged or disbarred.

The pile-on of prosecutions could create a chilling effect for campaigns in seeking recounts and reviews in close elections. That does not mean that there may not be evidence of knowing fraud or criminal wrongdoing. However, another anemic filing like the one in New York will only fuel the deep political divisions and unrest in the country. It needs to be clearly based on a desire for justice, rather than “just deserts.”

For Trump, of course, he may feel that (as Ray Charles sang) it always seems that “the road leads back to you” for Democratic prosecutors. That itself is not a problem so long as the road is both straight and well laid.

Loading…