Authored by Gail Tverberg via Our Finite World blog,

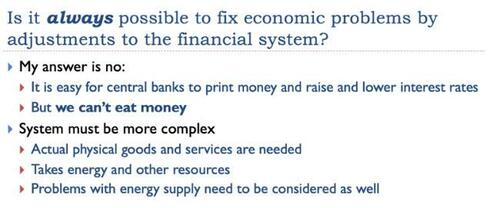

Time and time again, financial approaches have worked to fix economic problems. Raising interest rates has acted to slow the economy and lowering them has acted to speed up the economy. Governments overspending their incomes also acts to push the economy ahead; doing the reverse seems to slow economies down.

What could possibly go wrong? The issue is a physics problem. The economy doesn’t run simply on money and debt. It operates on resources of many kinds, including energy-related resources. As the population grows, the need for energy-related resources grows. The bottleneck that occurs is something that is hard to see in advance; it is an affordability bottleneck.

For a very long time, financial manipulations have been able to adjust affordability in a way that is optimal for most players. At some point, resources, especially energy resources, get stretched too thin, relative to the rising population and all the commitments that have been made, such as pension commitments. As a result, there is no way for the quantity of goods and services produced to grow sufficiently to match the promises that the financial system has made. This is the real bottleneck that the world economy reaches.

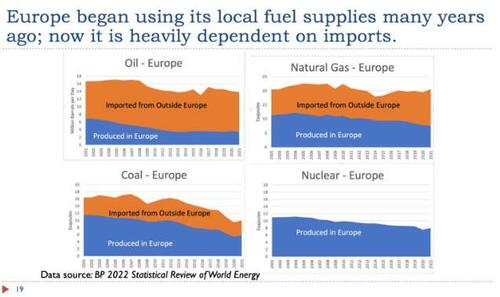

I believe that we are closely approaching this bottleneck today. I recently gave a talk to a group of European officials at the 2nd Luxembourg Strategy Conference, discussing the issue from the European point of view. Europeans seem to be especially vulnerable because Europe, with its early entry into the Industrial Revolution, substantially depleted its fossil fuel resources many years ago. The topic I was asked to discuss was, “Energy: The interconnection of energy limits and the economy and what this means for the future.”

In this post, I write about this presentation.

The major issue is that money, by itself, cannot operate the economy, because we cannot eat money. Any model of the economy must include energy and other resources. In a finite world, these resources tend to deplete. Also, human population tends to grow. At some point, not enough goods and services are produced for the growing population.

I believe that the major reason we have not been told about how the economy really works is because it would simply be too disturbing to understand the real situation. If today’s economy is dependent on finite fossil fuel supplies, it becomes clear that, at some point, these will run short. Then the world economy is likely to face a very difficult time.

A secondary reason for the confusion about how the economy operates is too much specialization by researchers studying the issue. Physicists (who are concerned about energy) don’t study economics; politicians and economists don’t study physics. As a result, neither group has a very broad understanding of the situation.

I am an actuary. I come from a different perspective: Will physical resources be adequate to meet financial promises being made? I have had the privilege of learning a little from both economic and physics sides of the discussion. I have also learned about the issue from a historical perspective.

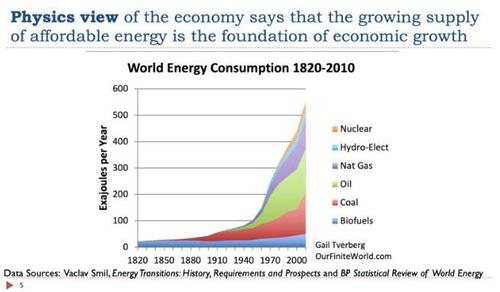

World energy consumption has been growing very rapidly at the same time that the world economy has been growing. This makes it hard to tell whether the growing energy supply enabled the economic growth, or whether the higher demand created by the growing economy encouraged the world economy to use more resources, including energy resources.

Physics says that it is energy resources that enable economic growth.

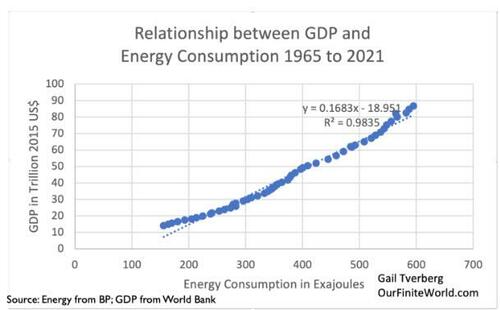

The R-squared of GDP as a function of energy is .98, relative to the equation shown.

Physicists talk about the “dissipation” of energy. In this process, the ability of an energy product to do “useful work” is depleted. For example, food is an energy product. When food is digested, its ability to do useful work (provide energy for our body) is used up. Cooking food, whether using a campfire or electricity or by burning natural gas, is another way of dissipating energy.

Humans are clearly part of the economy. Every type of work that is done depends upon energy dissipation. If energy supplies deplete, the form of the economy must change to match.

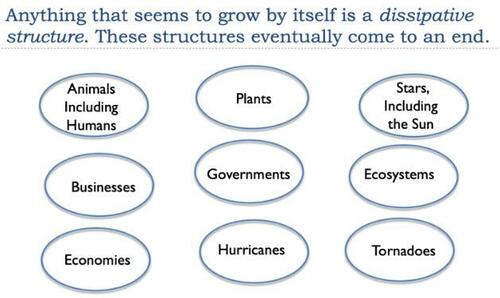

There are a huge number of systems that seem to grow by themselves using a process called self-organization. I have listed a few of these on Slide 8. Some of these things are alive; most are not. They are all called “dissipative structures.”

The key input that allows these systems to stay in a “non-dead” state is dissipation of energy of the appropriate type. For example, we know that humans need about 2,000 calories a day to continue to function properly. The mix of food must be approximately correct, too. Humans probably could not live on a diet of lettuce alone, for example.

Economies have their own need for energy supplies of the proper kind, or they don’t function properly. For example, today’s agricultural equipment, as well as today’s long-distance trucks, operate on diesel fuel. Without enough diesel fuel, it becomes impossible to plant and harvest crops and bring them to market. A transition to an all-electric system would take many, many years, if it could be done at all.

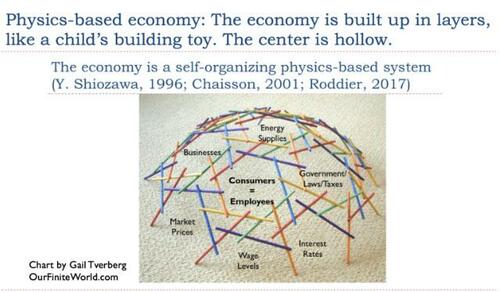

I think of an economy as being like a child’s building toy. Gradually, new participants are added, both in the form of new citizens and new businesses. Businesses are formed in response to expected changes in the markets. Governments gradually add new laws and new taxes. Supply and demand seem to set market prices. When the system seems to be operating poorly, regulators step in, typically adjusting interest rates and the availability of debt.

One key to keeping the economy working well is the fact that those who are “consumers” closely overlap those who are “employees.” The consumers (= employees) need to be paid well enough, or they cannot purchase the goods and services made by the economy.

A less obvious key to keeping the economy working well is that the whole system needs to be growing. This is necessary so that there are enough goods and services available for the growing population. A growing economy is also needed so that debt can be repaid with interest, and so that pension obligations can be paid as promised.

World population has been growing year after year, but arable land stays close to constant. To provide enough food for this rising population, more intensive agriculture is required, often including irrigation, fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides.

Furthermore, an increasing amount of fresh water is needed, leading to a need for deeper wells and, in some places, desalination to supplement other water sources. All these additional efforts add energy usage, as well as costs.

In addition, mineral ores and energy supplies of all kinds tend to become depleted because the best resources are accessed first. This leaves the more expensive-to-extract resources for later.

The issues in Slide 11 are a continuation of the issues described on Slide 10. The result is that the cost of energy production eventually rises so much that its higher costs spill over into the cost of all other goods and services. Workers find that their paychecks are not high enough to cover the items they usually purchased in the past. Some poor people cannot even afford food and fresh water.

Increasing debt is helpful as an economy grows. A farmer can borrow money for seed to grow a crop, and he can repay the debt, once the crop has grown. Or an entrepreneur can finance a factory using debt.

On the consumer side, debt at a sufficiently low interest rate can be used to make the purchase of a home or vehicle affordable.

Central banks and others involved in the financial world figured out many years ago that if they manipulate interest rates and the availability of credit, they are generally able to get the economy to grow as fast as they would like.

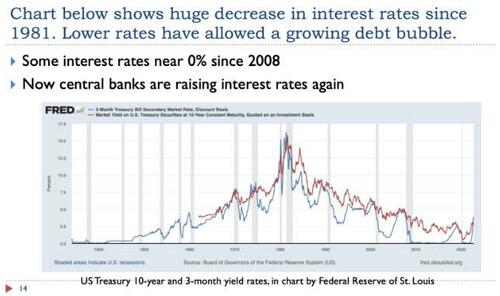

It is hard for most people to imagine how much interest rates have varied over the last century. Back during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the early 1940s, interest rates were very close to zero. As large amounts of inexpensive energy were added to the economy in the post-World War II period, the world economy raced ahead. It was possible to hold back growth by raising interest rates.

Oil supply was constrained in the 1970s, but demand and prices kept rising. US Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volker is known for raising interest rates to unheard of heights (over 15%) with a peak in 1981 to end inflation brought on by high oil prices. This high inflation rate brought on a huge recession from which the economy eventually recovered, as the higher prices brought more oil supply online (Alaska, North Sea, and Mexico), and as substitution was made for some oil use. For example, home heating was moved away from burning oil; electricity-production was mostly moved from oil to nuclear, coal and natural gas.

Another thing that has helped the economy since 1981 has been the ability to stimulate demand by lowering interest rates, making monthly payments more affordable. In 2008, the US added Quantitative Easing as a way of further holding interest rates down. A huge debt bubble has thus been built up since 1981, as the world economy has increasingly been operated with an increasing amount of debt at ever-lower interest rates. (See 3-month and 10 year interest rates shown on Slide 14.) This cheap debt has allowed rapidly rising asset prices.

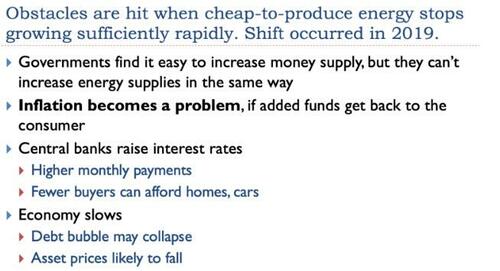

The world economy starts hitting major obstacles when energy supply stops growing faster than population because the supply of finished goods and services (such as new automobile, new homes, paved roads, and airplane trips for passengers) produced stops growing as rapidly as population. These obstacles take the form of affordability obstacles. The physics of the situation somehow causes the wages and wealth to be increasingly be concentrated among the top 10% or 1%. Lower-paid individuals are increasingly left out. While goods are still produced, ever-fewer workers can afford more than basic necessities. Such a situation makes for unhappy workers.

World energy consumption per capita hit a peak in 2018 and began to slide in 2019, with an even bigger drop in 2020. With less energy consumption, world automobile sales began to slide in 2019 and fell even lower in 2020. Protests, often indirectly related to inadequate wages or benefits, became an increasing problem in 2019. The year 2020 is known for Covid-19 related shutdowns and flight cancellations, but the indirect effect was to reduce energy consumption by less travel and by broken supply lines leading to unavailable goods. Prices of fossil fuels dropped far too low for producers.

Governments tried to get their own economies growing by various techniques, including spending more than the tax revenue they took in, leading to a need for more government debt, and by Quantitative Easing, acting to hold down interest rates. The result was a big increase in the money supply in many countries. This increased money supply was often distributed to individual citizens as subsidies of various kinds.

The higher demand caused by this additional money tended to cause inflation. It tended to raise fossil fuel prices because the inexpensive-to-extract fuels have mostly been extracted. In the days of Paul Volker, more energy supply at a little higher price was available within a few years. This seems extremely unlikely today because of diminishing returns. The problem is that there is little new oil supply available unless prices can stay above at least $120 per barrel on a consistent basis, and prices this high, or higher, do not seem to be available.

Oil prices are not rising this high, even with all of the stimulus funds because of the physics-based wage disparity problem mentioned previously. Also, those with political power try to keep fuel prices down so that the standards of living of citizens will not fall. Because of these low oil prices, OPEC+ continues to make cuts in production. The existence of chronically low prices for fossil fuels is likely the reason why Russia behaves in as belligerent a manner as it does today.

Today, with rising interest rates and Quantitative Tightening instead of Quantitative Easing, a major concern is that the debt bubble that has grown since in 1981 will start to collapse. With falling debt levels, prices of assets, such as homes, farms, and shares of stock, can be expected to fall. Many borrowers will be unable to repay their loans.

If this combination of events occurs, deflation is a likely outcome because banks and pension funds are likely to fail. If, somehow, local governments are able to bail out banks and pension funds, then there is a substantial likelihood of local hyperinflation. In such a case, people will have huge quantities of money, but practically nothing available to buy. In either case, the world economy will shrink because of inadequate energy supply.

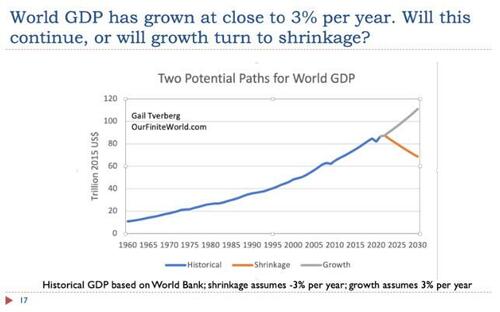

Most people have a “normalcy bias.” They assume that if economic growth has continued for a long time in the past, it necessarily will occur in the future. Yet, we all know that all dissipative structures somehow come to an end. Humans can come to an end in many ways: They can get hit by a car; they can catch an illness and succumb to it; they can die of old age; they can starve to death.

History tells us that economies nearly always collapse, usually over a period of years. Sometimes, population rises so high that the food production margin becomes tight; it becomes difficult to set aside enough food if the cycle of weather should turn for the worse. Thus, population drops when crops fail.

In the years leading up to collapse, it is common that the wages of ordinary citizens fall too low for them to be able to afford an adequate diet. In such a situation, epidemics can spread easily and kill many citizens. With so much poverty, it becomes impossible for governments to collect enough taxes to maintain services they have promised. Sometimes, nations lose at war because they cannot afford a suitable army. Very often, governmental debt becomes non-repayable.

The world economy today seems to be approaching some of the same bottlenecks that more local economies hit in the past.

The basic problem is that with inadequate energy supplies, the total quantity of goods and services provided by the economy must shrink. Thus, on average, people must become poorer. Most individual citizens, as well as most governments, will not be happy about this situation.

The situation becomes very much like the game of musical chairs. In this game, one chair at a time is removed. The players walk around the chairs while music plays. When the music stops, all participants grab for a chair. Someone gets left out. In the case of energy supplies, the stronger countries will try to push aside the weaker competitors.

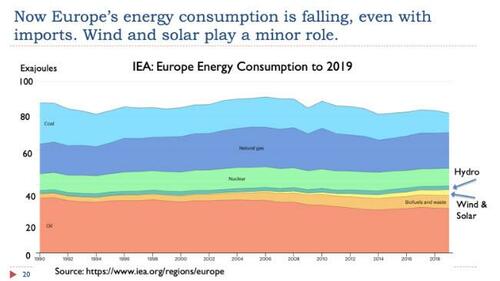

Countries that understand the importance of adequate energy supplies recognize that Europe is relatively weak because of its dependence on imported fuel. However, Europe seems to be oblivious to its poor position, attempting to dictate to others how important it is to prevent climate change by eliminating fossil fuels. With this view, it can easily keep its high opinion of itself.

If we think about the musical chairs’ situation and not enough energy supplies to go around, everyone in the world (except Europe) would be better off if Europe were to be forced out of its high imports of fossil fuels. Russia could perhaps obtain higher energy export prices in Asia and the Far East. The whole situation becomes very strange. Europe tells itself it is cutting off imports to punish Russia. But, if Europe’s imports can remain very low, everyone else, from the US, to Russia, to China, to Japan would benefit.

The benefits of wind and solar energy are glorified in Europe, with people being led to believe that it would be easy to transition from fossil fuels, and perhaps leave nuclear, as well. The problem is that wind, solar, and even hydroelectric energy supply are very undependable. They cannot ever be ramped up to provide year-round heat. They are poorly adapted for agricultural use (except for sunshine helping crops grow).

Few people realize that the benefits that wind and solar provide are tiny. They cannot be depended on, so companies providing electricity need to maintain duplicate generating capacity. Wind and solar require far more transmission than fossil-fuel-generated electricity because the best sources are often far from population centers. When all costs are included (without subsidy), wind and solar electricity tend to be more expensive than fossil-fuel generated electricity. They are especially difficult to rely on in winter. Therefore, many people in Europe are concerned about possibly “freezing in the dark,” as soon as this winter.

There is no possibility of ever transitioning to a system that operates only on intermittent electricity with the population that Europe has today, or that the world has today. Wind turbines and solar panels are built and maintained using fossil fuel energy. Transmission lines cannot be maintained using intermittent electricity alone.

Basically, Europe must use very much less fossil fuel energy, for the long term. Citizens cannot assume that the war with Ukraine will soon be over, and everything will be back to the way it was several years ago. It is much more likely that the freeze-in-the-dark problem will be present every winter, from now on. In fact, European citizens might actually be happier if the climate would warm up a bit.

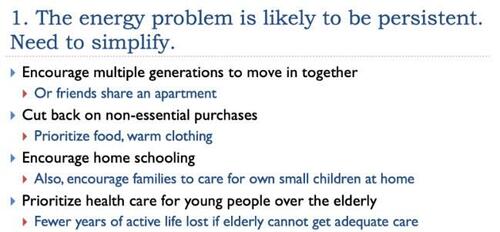

With this as background, there is a need to figure out how to use less energy without hurting lifestyles too badly. To some extent, changes from the Covid-19 shutdowns can be used, since these indirectly were ways of saving energy. Furthermore, if families can move in together, fewer buildings in total will need to be heated. Cooking can perhaps be done for larger groups at a time, saving on fuel.

If families can home-school their children, this saves both the energy for transportation to school and the energy for heating the school. If families can keep younger children at home, instead of sending them to daycare, this saves energy, as well.

A major issue that I do not point out directly in this presentation is the high energy cost of supporting the elderly in the lifestyles to which they have become accustomed. One issue is the huge amount and cost of healthcare. Another is the cost of separate residences. These costs can be reduced if the elderly can be persuaded to move in with family members, as was done in the past. Pension programs worldwide are running into financial difficulty now, with interest rates rising. Countries with large elderly populations are likely to be especially affected.

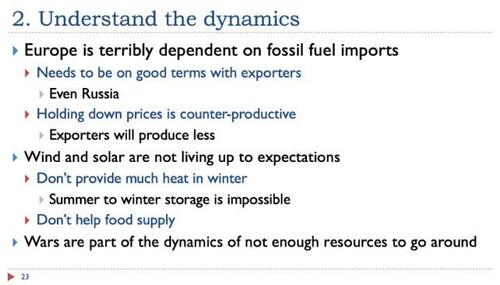

Besides conserving energy, the other thing people in Europe can do is attempt to understand the dynamics of our current situation. We are in a different world now, with not enough energy of the right kinds to go around.

The dynamics in a world of energy shortages are like those of the musical chairs’ game. We can expect more fighting. We cannot expect that countries that have been on our side in the past will necessarily be on our side in the future. It is more like being in an undeclared war with many participants.

Under ideal circumstances, Europe would be on good terms with energy exporters, even Russia. I suppose at this late date, nothing can be done.

A major issue is that if Europe attempts to hold down fossil fuel prices, the indirect result will be to reduce supply. Oil, natural gas and coal producers will all reduce supply before they will accept a price that they consider too low. Given the dependence of the world economy on energy supplies, especially fossil fuel energy supplies, this will make the situation worse, rather than better.

Wind and solar are not replacements for fossil fuels. They are made with fossil fuels. We don’t have the ability to store up solar energy from summer to winter. Wind is also too undependable, and battery capacity too low, to compensate for need for storage from season to season. Thus, without a growing supply of fossil fuels, it is impossible for today’s economy to continue in its current form.

Authored by Gail Tverberg via Our Finite World blog,

Time and time again, financial approaches have worked to fix economic problems. Raising interest rates has acted to slow the economy and lowering them has acted to speed up the economy. Governments overspending their incomes also acts to push the economy ahead; doing the reverse seems to slow economies down.

What could possibly go wrong? The issue is a physics problem. The economy doesn’t run simply on money and debt. It operates on resources of many kinds, including energy-related resources. As the population grows, the need for energy-related resources grows. The bottleneck that occurs is something that is hard to see in advance; it is an affordability bottleneck.

For a very long time, financial manipulations have been able to adjust affordability in a way that is optimal for most players. At some point, resources, especially energy resources, get stretched too thin, relative to the rising population and all the commitments that have been made, such as pension commitments. As a result, there is no way for the quantity of goods and services produced to grow sufficiently to match the promises that the financial system has made. This is the real bottleneck that the world economy reaches.

I believe that we are closely approaching this bottleneck today. I recently gave a talk to a group of European officials at the 2nd Luxembourg Strategy Conference, discussing the issue from the European point of view. Europeans seem to be especially vulnerable because Europe, with its early entry into the Industrial Revolution, substantially depleted its fossil fuel resources many years ago. The topic I was asked to discuss was, “Energy: The interconnection of energy limits and the economy and what this means for the future.”

In this post, I write about this presentation.

The major issue is that money, by itself, cannot operate the economy, because we cannot eat money. Any model of the economy must include energy and other resources. In a finite world, these resources tend to deplete. Also, human population tends to grow. At some point, not enough goods and services are produced for the growing population.

I believe that the major reason we have not been told about how the economy really works is because it would simply be too disturbing to understand the real situation. If today’s economy is dependent on finite fossil fuel supplies, it becomes clear that, at some point, these will run short. Then the world economy is likely to face a very difficult time.

A secondary reason for the confusion about how the economy operates is too much specialization by researchers studying the issue. Physicists (who are concerned about energy) don’t study economics; politicians and economists don’t study physics. As a result, neither group has a very broad understanding of the situation.

I am an actuary. I come from a different perspective: Will physical resources be adequate to meet financial promises being made? I have had the privilege of learning a little from both economic and physics sides of the discussion. I have also learned about the issue from a historical perspective.

World energy consumption has been growing very rapidly at the same time that the world economy has been growing. This makes it hard to tell whether the growing energy supply enabled the economic growth, or whether the higher demand created by the growing economy encouraged the world economy to use more resources, including energy resources.

Physics says that it is energy resources that enable economic growth.

The R-squared of GDP as a function of energy is .98, relative to the equation shown.

Physicists talk about the “dissipation” of energy. In this process, the ability of an energy product to do “useful work” is depleted. For example, food is an energy product. When food is digested, its ability to do useful work (provide energy for our body) is used up. Cooking food, whether using a campfire or electricity or by burning natural gas, is another way of dissipating energy.

Humans are clearly part of the economy. Every type of work that is done depends upon energy dissipation. If energy supplies deplete, the form of the economy must change to match.

There are a huge number of systems that seem to grow by themselves using a process called self-organization. I have listed a few of these on Slide 8. Some of these things are alive; most are not. They are all called “dissipative structures.”

The key input that allows these systems to stay in a “non-dead” state is dissipation of energy of the appropriate type. For example, we know that humans need about 2,000 calories a day to continue to function properly. The mix of food must be approximately correct, too. Humans probably could not live on a diet of lettuce alone, for example.

Economies have their own need for energy supplies of the proper kind, or they don’t function properly. For example, today’s agricultural equipment, as well as today’s long-distance trucks, operate on diesel fuel. Without enough diesel fuel, it becomes impossible to plant and harvest crops and bring them to market. A transition to an all-electric system would take many, many years, if it could be done at all.

I think of an economy as being like a child’s building toy. Gradually, new participants are added, both in the form of new citizens and new businesses. Businesses are formed in response to expected changes in the markets. Governments gradually add new laws and new taxes. Supply and demand seem to set market prices. When the system seems to be operating poorly, regulators step in, typically adjusting interest rates and the availability of debt.

One key to keeping the economy working well is the fact that those who are “consumers” closely overlap those who are “employees.” The consumers (= employees) need to be paid well enough, or they cannot purchase the goods and services made by the economy.

A less obvious key to keeping the economy working well is that the whole system needs to be growing. This is necessary so that there are enough goods and services available for the growing population. A growing economy is also needed so that debt can be repaid with interest, and so that pension obligations can be paid as promised.

World population has been growing year after year, but arable land stays close to constant. To provide enough food for this rising population, more intensive agriculture is required, often including irrigation, fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides.

Furthermore, an increasing amount of fresh water is needed, leading to a need for deeper wells and, in some places, desalination to supplement other water sources. All these additional efforts add energy usage, as well as costs.

In addition, mineral ores and energy supplies of all kinds tend to become depleted because the best resources are accessed first. This leaves the more expensive-to-extract resources for later.

The issues in Slide 11 are a continuation of the issues described on Slide 10. The result is that the cost of energy production eventually rises so much that its higher costs spill over into the cost of all other goods and services. Workers find that their paychecks are not high enough to cover the items they usually purchased in the past. Some poor people cannot even afford food and fresh water.

Increasing debt is helpful as an economy grows. A farmer can borrow money for seed to grow a crop, and he can repay the debt, once the crop has grown. Or an entrepreneur can finance a factory using debt.

On the consumer side, debt at a sufficiently low interest rate can be used to make the purchase of a home or vehicle affordable.

Central banks and others involved in the financial world figured out many years ago that if they manipulate interest rates and the availability of credit, they are generally able to get the economy to grow as fast as they would like.

It is hard for most people to imagine how much interest rates have varied over the last century. Back during the Great Depression of the 1930s and the early 1940s, interest rates were very close to zero. As large amounts of inexpensive energy were added to the economy in the post-World War II period, the world economy raced ahead. It was possible to hold back growth by raising interest rates.

Oil supply was constrained in the 1970s, but demand and prices kept rising. US Federal Reserve Chairman Paul Volker is known for raising interest rates to unheard of heights (over 15%) with a peak in 1981 to end inflation brought on by high oil prices. This high inflation rate brought on a huge recession from which the economy eventually recovered, as the higher prices brought more oil supply online (Alaska, North Sea, and Mexico), and as substitution was made for some oil use. For example, home heating was moved away from burning oil; electricity-production was mostly moved from oil to nuclear, coal and natural gas.

Another thing that has helped the economy since 1981 has been the ability to stimulate demand by lowering interest rates, making monthly payments more affordable. In 2008, the US added Quantitative Easing as a way of further holding interest rates down. A huge debt bubble has thus been built up since 1981, as the world economy has increasingly been operated with an increasing amount of debt at ever-lower interest rates. (See 3-month and 10 year interest rates shown on Slide 14.) This cheap debt has allowed rapidly rising asset prices.

The world economy starts hitting major obstacles when energy supply stops growing faster than population because the supply of finished goods and services (such as new automobile, new homes, paved roads, and airplane trips for passengers) produced stops growing as rapidly as population. These obstacles take the form of affordability obstacles. The physics of the situation somehow causes the wages and wealth to be increasingly be concentrated among the top 10% or 1%. Lower-paid individuals are increasingly left out. While goods are still produced, ever-fewer workers can afford more than basic necessities. Such a situation makes for unhappy workers.

World energy consumption per capita hit a peak in 2018 and began to slide in 2019, with an even bigger drop in 2020. With less energy consumption, world automobile sales began to slide in 2019 and fell even lower in 2020. Protests, often indirectly related to inadequate wages or benefits, became an increasing problem in 2019. The year 2020 is known for Covid-19 related shutdowns and flight cancellations, but the indirect effect was to reduce energy consumption by less travel and by broken supply lines leading to unavailable goods. Prices of fossil fuels dropped far too low for producers.

Governments tried to get their own economies growing by various techniques, including spending more than the tax revenue they took in, leading to a need for more government debt, and by Quantitative Easing, acting to hold down interest rates. The result was a big increase in the money supply in many countries. This increased money supply was often distributed to individual citizens as subsidies of various kinds.

The higher demand caused by this additional money tended to cause inflation. It tended to raise fossil fuel prices because the inexpensive-to-extract fuels have mostly been extracted. In the days of Paul Volker, more energy supply at a little higher price was available within a few years. This seems extremely unlikely today because of diminishing returns. The problem is that there is little new oil supply available unless prices can stay above at least $120 per barrel on a consistent basis, and prices this high, or higher, do not seem to be available.

Oil prices are not rising this high, even with all of the stimulus funds because of the physics-based wage disparity problem mentioned previously. Also, those with political power try to keep fuel prices down so that the standards of living of citizens will not fall. Because of these low oil prices, OPEC+ continues to make cuts in production. The existence of chronically low prices for fossil fuels is likely the reason why Russia behaves in as belligerent a manner as it does today.

Today, with rising interest rates and Quantitative Tightening instead of Quantitative Easing, a major concern is that the debt bubble that has grown since in 1981 will start to collapse. With falling debt levels, prices of assets, such as homes, farms, and shares of stock, can be expected to fall. Many borrowers will be unable to repay their loans.

If this combination of events occurs, deflation is a likely outcome because banks and pension funds are likely to fail. If, somehow, local governments are able to bail out banks and pension funds, then there is a substantial likelihood of local hyperinflation. In such a case, people will have huge quantities of money, but practically nothing available to buy. In either case, the world economy will shrink because of inadequate energy supply.

Most people have a “normalcy bias.” They assume that if economic growth has continued for a long time in the past, it necessarily will occur in the future. Yet, we all know that all dissipative structures somehow come to an end. Humans can come to an end in many ways: They can get hit by a car; they can catch an illness and succumb to it; they can die of old age; they can starve to death.

History tells us that economies nearly always collapse, usually over a period of years. Sometimes, population rises so high that the food production margin becomes tight; it becomes difficult to set aside enough food if the cycle of weather should turn for the worse. Thus, population drops when crops fail.

In the years leading up to collapse, it is common that the wages of ordinary citizens fall too low for them to be able to afford an adequate diet. In such a situation, epidemics can spread easily and kill many citizens. With so much poverty, it becomes impossible for governments to collect enough taxes to maintain services they have promised. Sometimes, nations lose at war because they cannot afford a suitable army. Very often, governmental debt becomes non-repayable.

The world economy today seems to be approaching some of the same bottlenecks that more local economies hit in the past.

The basic problem is that with inadequate energy supplies, the total quantity of goods and services provided by the economy must shrink. Thus, on average, people must become poorer. Most individual citizens, as well as most governments, will not be happy about this situation.

The situation becomes very much like the game of musical chairs. In this game, one chair at a time is removed. The players walk around the chairs while music plays. When the music stops, all participants grab for a chair. Someone gets left out. In the case of energy supplies, the stronger countries will try to push aside the weaker competitors.

Countries that understand the importance of adequate energy supplies recognize that Europe is relatively weak because of its dependence on imported fuel. However, Europe seems to be oblivious to its poor position, attempting to dictate to others how important it is to prevent climate change by eliminating fossil fuels. With this view, it can easily keep its high opinion of itself.

If we think about the musical chairs’ situation and not enough energy supplies to go around, everyone in the world (except Europe) would be better off if Europe were to be forced out of its high imports of fossil fuels. Russia could perhaps obtain higher energy export prices in Asia and the Far East. The whole situation becomes very strange. Europe tells itself it is cutting off imports to punish Russia. But, if Europe’s imports can remain very low, everyone else, from the US, to Russia, to China, to Japan would benefit.

The benefits of wind and solar energy are glorified in Europe, with people being led to believe that it would be easy to transition from fossil fuels, and perhaps leave nuclear, as well. The problem is that wind, solar, and even hydroelectric energy supply are very undependable. They cannot ever be ramped up to provide year-round heat. They are poorly adapted for agricultural use (except for sunshine helping crops grow).

Few people realize that the benefits that wind and solar provide are tiny. They cannot be depended on, so companies providing electricity need to maintain duplicate generating capacity. Wind and solar require far more transmission than fossil-fuel-generated electricity because the best sources are often far from population centers. When all costs are included (without subsidy), wind and solar electricity tend to be more expensive than fossil-fuel generated electricity. They are especially difficult to rely on in winter. Therefore, many people in Europe are concerned about possibly “freezing in the dark,” as soon as this winter.

There is no possibility of ever transitioning to a system that operates only on intermittent electricity with the population that Europe has today, or that the world has today. Wind turbines and solar panels are built and maintained using fossil fuel energy. Transmission lines cannot be maintained using intermittent electricity alone.

Basically, Europe must use very much less fossil fuel energy, for the long term. Citizens cannot assume that the war with Ukraine will soon be over, and everything will be back to the way it was several years ago. It is much more likely that the freeze-in-the-dark problem will be present every winter, from now on. In fact, European citizens might actually be happier if the climate would warm up a bit.

With this as background, there is a need to figure out how to use less energy without hurting lifestyles too badly. To some extent, changes from the Covid-19 shutdowns can be used, since these indirectly were ways of saving energy. Furthermore, if families can move in together, fewer buildings in total will need to be heated. Cooking can perhaps be done for larger groups at a time, saving on fuel.

If families can home-school their children, this saves both the energy for transportation to school and the energy for heating the school. If families can keep younger children at home, instead of sending them to daycare, this saves energy, as well.

A major issue that I do not point out directly in this presentation is the high energy cost of supporting the elderly in the lifestyles to which they have become accustomed. One issue is the huge amount and cost of healthcare. Another is the cost of separate residences. These costs can be reduced if the elderly can be persuaded to move in with family members, as was done in the past. Pension programs worldwide are running into financial difficulty now, with interest rates rising. Countries with large elderly populations are likely to be especially affected.

Besides conserving energy, the other thing people in Europe can do is attempt to understand the dynamics of our current situation. We are in a different world now, with not enough energy of the right kinds to go around.

The dynamics in a world of energy shortages are like those of the musical chairs’ game. We can expect more fighting. We cannot expect that countries that have been on our side in the past will necessarily be on our side in the future. It is more like being in an undeclared war with many participants.

Under ideal circumstances, Europe would be on good terms with energy exporters, even Russia. I suppose at this late date, nothing can be done.

A major issue is that if Europe attempts to hold down fossil fuel prices, the indirect result will be to reduce supply. Oil, natural gas and coal producers will all reduce supply before they will accept a price that they consider too low. Given the dependence of the world economy on energy supplies, especially fossil fuel energy supplies, this will make the situation worse, rather than better.

Wind and solar are not replacements for fossil fuels. They are made with fossil fuels. We don’t have the ability to store up solar energy from summer to winter. Wind is also too undependable, and battery capacity too low, to compensate for need for storage from season to season. Thus, without a growing supply of fossil fuels, it is impossible for today’s economy to continue in its current form.