Submitted by Leonard Hyman and William Tilles for Oilprice.com,

Last week, Washington, D.C. based Last Energy announced that it had signed agreements in the UK and Poland for thirty four small modular reactors. Frankly, when we first saw the headline we assumed editorial failure by the UK press and moved on. But our initial impression was wrong. These are among the tiniest modular reactor designs we have seen to date, producing a mere 20 MWs of electricity. All of the 34 orders cited above collectively equal about one half of a gigawatt scale power plant regardless of type. By contrast the proposed NuScale reactors produce 77 MWs and the GE Hitachi BWRX 300 reactor under consideration by TVA for its Clinch River site is, as the name implies, 300 MWs. But size is not the only thing that differentiates Last Energy from its more conventional competitors. Last Energy is unusual in that its financial backing comes from libertarian, Silicon Valley funders who typically have been portrayed in the press as “disrupters”. Last’s CEO, Bret Kugelmass, started a Washington D.C. based think tank, the Energy Impact Center, “which sought to answer the ultimate question of our lifetime: how to reverse climate change. Nuclear is the answer.” They also sponsored a podcast, ”Titans of Nuclear”, featuring many experts and issues in the field. Our point here is that this company bears little resemblance to the conventional array of government-backed defense contractors representing most of the other SMR technologies. Given its background, not surprisingly Last Energy sounds to us a bit like Uber or WeWork but for new nukes. Their lofty and worthwhile goal is to reverse the impacts of climate utilizing off the shelf nuclear technology with an innovative delivery mode. Their claim is to “follow the best practices of the renewables industry: scaling of quantity rather than size.”

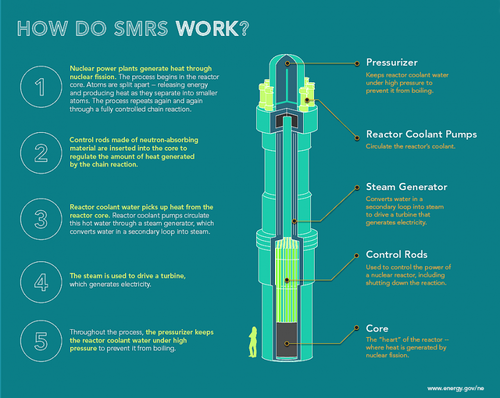

Their offering is a compact 20 MW, single loop, pressurized water reactor that could sit on a site of ½ an acre. It would use conventional nuclear fuel, 4.95% enriched uranium and standard fuel rods in a 17 by 17 array. The build time is estimated to be just 30 months. But, given the full modularity of all plant structures the estimated actual on site construction time is estimated at just three months. The fuel cycle is a lengthy 72 months with a three month refueling interval. These plants would also be air cooled and the company touted its meager water usage of a mere 8 gallons per minute. This contrasts with the significant water demands of other even relatively small reactors. Like other smaller reactors the Last Energy design would feature a “subterranean nuclear island” and “low profile balance of plant”. Gone are the big reinforced domes or rectangles of previous designs that could withstand whatever hypothetical impact short of an asteroid. They describe their approach as “customer centric” and that “our innovation is simple; leverage only proven nuclear technology, create a replicable, manufacturable power plant, and size for private capital.” The first actual plant installations could occur as soon as 2025 or 2026. No other SMR builder is offering a new plant much before 2029.

In terms of cost, the UK press cited a figure of £100 million or less per 20 MW unit, or about $6,135 per kw. This was for a total of 34 European reactors, 24 in the UK and 10 in Poland. Romania is also considering the design. The company has secured PPAs, purchase power agreements, with 4 industrial partners. In Poland they are partnering with the Katowice Special Economic Zone in southwest Poland. In the UK they have three industrial partnerships only identified as “a life sciences campus, a sustainable fuels manufacturer, and a developer of hyperscale data centers.” Last Energy is unique in that they offer “one stop shopping” for nuclear energy purchasers. They state that, “We cover all aspects of the investment process including design, construction, financing, service, and operation.”

The European Nuclear Energy Agency, which monitors nuclear issues, currently lists no fewer than twenty one promising nuclear technologies on its SMR dashboard. (Last Energy’s PWR 20 is not currently listed.) There are multiple entries in each of the five categories of new, small nuclear technology: water cooled, gas cooled, fast spectrum, micro (which would include Last Energy), and molten salt. The dashboard approach ranks these various technologies on five criteria: licensing, siting, supply chain, engagement, and fuel. None of these technologies has as yet been commercially licensed outside of China and Russia. The NEA stated that less than half of the featured technologies could obtain financing for a first-of-its-kind unit and an even smaller subset would be able to obtain purchase power agreements, which Last Energy has done.

The one major difference between say the BWRX 300 or NuScale versus Last’s PWR 20 is with respect to licensing. The first two companies go to great lengths to describe and advertise their proximity to regulatory approvals. Last’s website notes that the “Biggest uncertainties (are) posed by the licensing process.” They further state their hope that in terms of design development “we are able to fabricate in parallel with our licensing process”. Regardless of how they describe the regulatory/licensing process, the NEA summarizes the basic process in the US and Europe as consisting of four essential steps: 1) pre-licensing interaction with regulators, 2) design approval, 3) construction, and finally 4) issuance of an operating license and commercial operation. Stated differently, it won’t matter how quickly Last Energy engineers can fabricate and assemble their PWR 20 until various regulators approve their design.

From a commercial acceptance perspective, it is difficult to even hazard a guess about future SMR technology since we’re really talking about a replacement cycle, mostly for aging natural gas power plants in the 2040s. Assuming that a new generation of SMRs begin operating at the end of this decade as planned, there is no reason to believe the market will coalesce around one SMR size or technology much before the mid to late 2030s. Right now all we can say broadly is that there seem to be two markets for SMRs, the almost utility scale reactors producing 300 MWs like the BWRX model and micro reactors in the 5-50 MW range including Last Energy. And that these are being pitched to very different types of customers. Electric utilities have been gravitating towards larger reactors for reasons of cost, bigger is still considered cheaper. Smaller reactors on the other hand have appeal for inside the fence commercial and industrial activities, provision of process steam, and compatibility with district heating systems. And this is where Last Energy seems to be making some inroads.

In the end, though, neither the technical nor business prowess of Last will prevail if the public becomes uncomfortable with the idea of mini nukes spread over the landscape. These will have to be guarded against terrorists, possibly by weak governments, and whose waste has to be transported through neighborhoods and communities to facilities not yet built. Mini nukes look good on paper. But as they say in automotive circles, “Let’s wait until the rubber hits the road.” Something better might come along while we wait.

Submitted by Leonard Hyman and William Tilles for Oilprice.com,

Last week, Washington, D.C. based Last Energy announced that it had signed agreements in the UK and Poland for thirty four small modular reactors. Frankly, when we first saw the headline we assumed editorial failure by the UK press and moved on. But our initial impression was wrong. These are among the tiniest modular reactor designs we have seen to date, producing a mere 20 MWs of electricity. All of the 34 orders cited above collectively equal about one half of a gigawatt scale power plant regardless of type. By contrast the proposed NuScale reactors produce 77 MWs and the GE Hitachi BWRX 300 reactor under consideration by TVA for its Clinch River site is, as the name implies, 300 MWs. But size is not the only thing that differentiates Last Energy from its more conventional competitors. Last Energy is unusual in that its financial backing comes from libertarian, Silicon Valley funders who typically have been portrayed in the press as “disrupters”. Last’s CEO, Bret Kugelmass, started a Washington D.C. based think tank, the Energy Impact Center, “which sought to answer the ultimate question of our lifetime: how to reverse climate change. Nuclear is the answer.” They also sponsored a podcast, ”Titans of Nuclear”, featuring many experts and issues in the field. Our point here is that this company bears little resemblance to the conventional array of government-backed defense contractors representing most of the other SMR technologies. Given its background, not surprisingly Last Energy sounds to us a bit like Uber or WeWork but for new nukes. Their lofty and worthwhile goal is to reverse the impacts of climate utilizing off the shelf nuclear technology with an innovative delivery mode. Their claim is to “follow the best practices of the renewables industry: scaling of quantity rather than size.”

Their offering is a compact 20 MW, single loop, pressurized water reactor that could sit on a site of ½ an acre. It would use conventional nuclear fuel, 4.95% enriched uranium and standard fuel rods in a 17 by 17 array. The build time is estimated to be just 30 months. But, given the full modularity of all plant structures the estimated actual on site construction time is estimated at just three months. The fuel cycle is a lengthy 72 months with a three month refueling interval. These plants would also be air cooled and the company touted its meager water usage of a mere 8 gallons per minute. This contrasts with the significant water demands of other even relatively small reactors. Like other smaller reactors the Last Energy design would feature a “subterranean nuclear island” and “low profile balance of plant”. Gone are the big reinforced domes or rectangles of previous designs that could withstand whatever hypothetical impact short of an asteroid. They describe their approach as “customer centric” and that “our innovation is simple; leverage only proven nuclear technology, create a replicable, manufacturable power plant, and size for private capital.” The first actual plant installations could occur as soon as 2025 or 2026. No other SMR builder is offering a new plant much before 2029.

In terms of cost, the UK press cited a figure of £100 million or less per 20 MW unit, or about $6,135 per kw. This was for a total of 34 European reactors, 24 in the UK and 10 in Poland. Romania is also considering the design. The company has secured PPAs, purchase power agreements, with 4 industrial partners. In Poland they are partnering with the Katowice Special Economic Zone in southwest Poland. In the UK they have three industrial partnerships only identified as “a life sciences campus, a sustainable fuels manufacturer, and a developer of hyperscale data centers.” Last Energy is unique in that they offer “one stop shopping” for nuclear energy purchasers. They state that, “We cover all aspects of the investment process including design, construction, financing, service, and operation.”

The European Nuclear Energy Agency, which monitors nuclear issues, currently lists no fewer than twenty one promising nuclear technologies on its SMR dashboard. (Last Energy’s PWR 20 is not currently listed.) There are multiple entries in each of the five categories of new, small nuclear technology: water cooled, gas cooled, fast spectrum, micro (which would include Last Energy), and molten salt. The dashboard approach ranks these various technologies on five criteria: licensing, siting, supply chain, engagement, and fuel. None of these technologies has as yet been commercially licensed outside of China and Russia. The NEA stated that less than half of the featured technologies could obtain financing for a first-of-its-kind unit and an even smaller subset would be able to obtain purchase power agreements, which Last Energy has done.

The one major difference between say the BWRX 300 or NuScale versus Last’s PWR 20 is with respect to licensing. The first two companies go to great lengths to describe and advertise their proximity to regulatory approvals. Last’s website notes that the “Biggest uncertainties (are) posed by the licensing process.” They further state their hope that in terms of design development “we are able to fabricate in parallel with our licensing process”. Regardless of how they describe the regulatory/licensing process, the NEA summarizes the basic process in the US and Europe as consisting of four essential steps: 1) pre-licensing interaction with regulators, 2) design approval, 3) construction, and finally 4) issuance of an operating license and commercial operation. Stated differently, it won’t matter how quickly Last Energy engineers can fabricate and assemble their PWR 20 until various regulators approve their design.

From a commercial acceptance perspective, it is difficult to even hazard a guess about future SMR technology since we’re really talking about a replacement cycle, mostly for aging natural gas power plants in the 2040s. Assuming that a new generation of SMRs begin operating at the end of this decade as planned, there is no reason to believe the market will coalesce around one SMR size or technology much before the mid to late 2030s. Right now all we can say broadly is that there seem to be two markets for SMRs, the almost utility scale reactors producing 300 MWs like the BWRX model and micro reactors in the 5-50 MW range including Last Energy. And that these are being pitched to very different types of customers. Electric utilities have been gravitating towards larger reactors for reasons of cost, bigger is still considered cheaper. Smaller reactors on the other hand have appeal for inside the fence commercial and industrial activities, provision of process steam, and compatibility with district heating systems. And this is where Last Energy seems to be making some inroads.

In the end, though, neither the technical nor business prowess of Last will prevail if the public becomes uncomfortable with the idea of mini nukes spread over the landscape. These will have to be guarded against terrorists, possibly by weak governments, and whose waste has to be transported through neighborhoods and communities to facilities not yet built. Mini nukes look good on paper. But as they say in automotive circles, “Let’s wait until the rubber hits the road.” Something better might come along while we wait.

Loading…