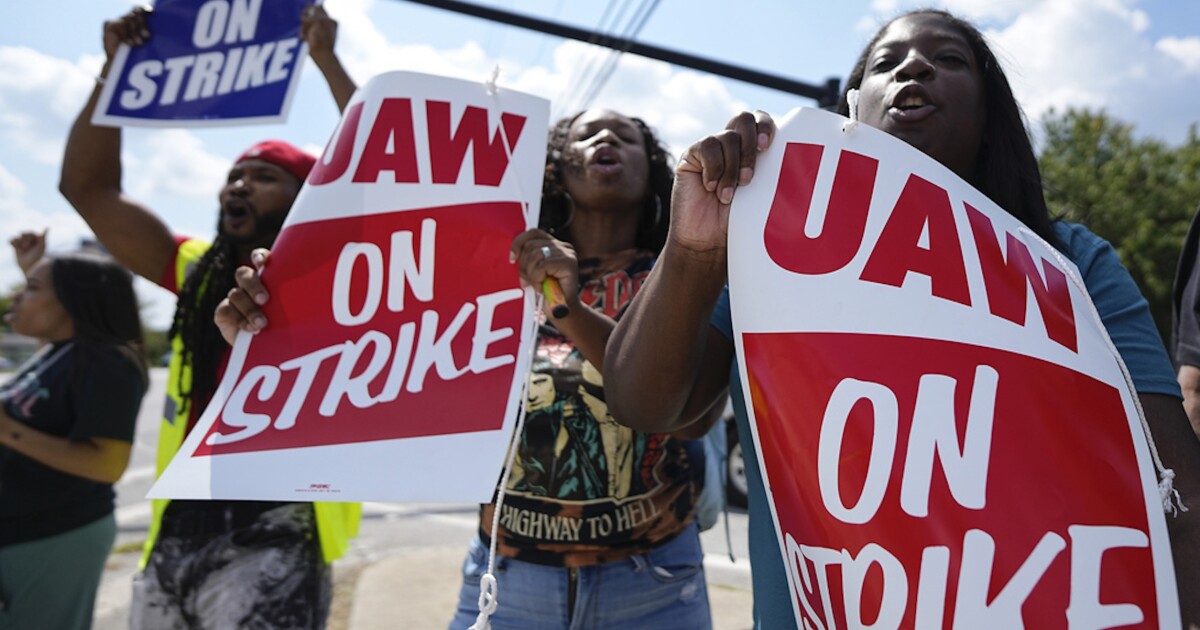

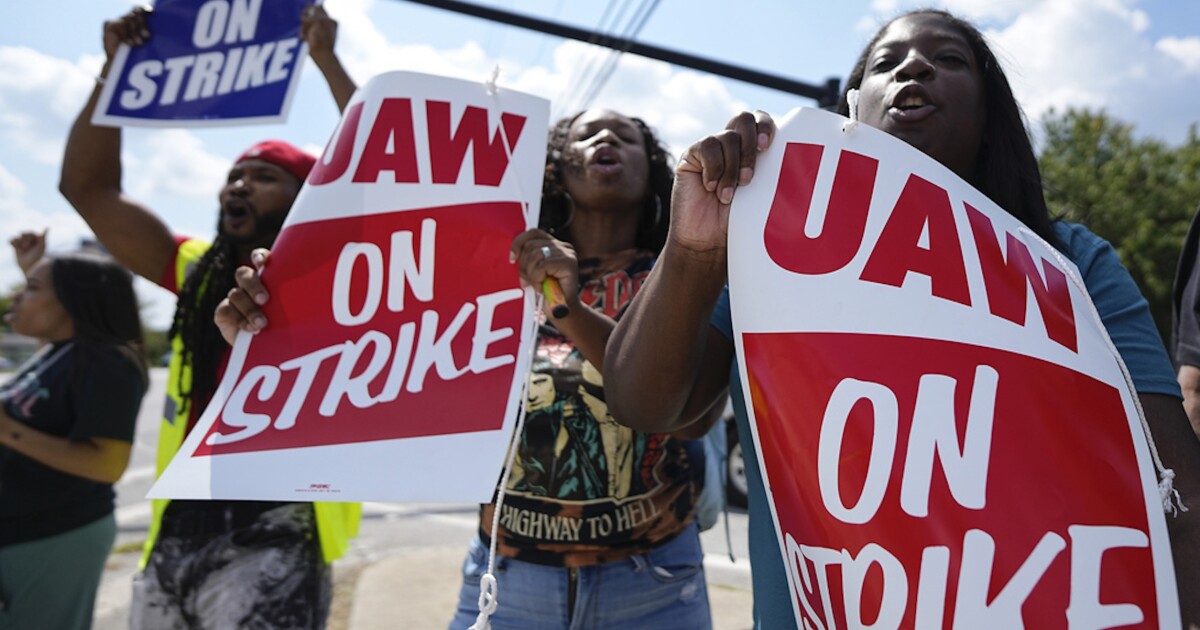

Amid a “perfect storm” of factors, organized labor and strikes have drawn major attention this year, a boon for unions.

Ford, General Motors, Stellantis, UPS, railroad companies, Amazon, Starbucks, Kaiser Permanente, and Hollywood all share one thing in common — they have all drawn major headlines for being at the center of labor union disputes over the past three years, or roughly since President Joe Biden was sworn into office.

EMPLOYMENT GROWTH CRUSHES EXPECTATIONS WITH 336,000 JOBS ADDED IN SEPTEMBER

The contract battles, pitting union bosses like UAW President Shawn Fain against massive corporations, have garnered a huge amount of media attention and elevated broader interest in labor unions and strikes to a level not seen in decades, according to Dan Bowling, a distinguished fellow at Duke University School of Law.

“Far more,” Bowling told the Washington Examiner about the level of attention that unions are receiving now compared to just a few years ago. He said that back then, it just “wasn’t at the top of the radar screen.”

Right now, UAW workers are three weeks into strikes at dozens of Ford, GM, and Stellantis plants across the country. Fain’s Facebook livestreams capture tens of thousands of viewers as the union fights for lucrative contract terms. President Joe Biden even joined the UAW picket line.

Earlier this summer UPS was top of mind as the Teamsters pushed negotiations right up to the deadline for a strike. A strike would have reverberated through the economy and roiled supply chains, as some 6% of the country’s GDP travels through UPS, and the labor contract represents the largest private-sector union agreement in North America.

And before that, rail worker unions threatened another strike that would have snarled the country’s supply chains right in the middle of last year’s holiday season. The situation put Biden, who has fashioned himself as the most union-friendly president in history, between a rock and a hard place. The specter of a mass rail strike prompted Biden and Congress to intervene and impose a contract on the workers, which drew criticism from labor advocates.

Even further back, in late 2020, the first Starbucks store in the U.S. voted to unionize. That set off a wave of other efforts at stores across the country, and now workers at the company have won union elections at some 300 locations.

Last year, an Amazon warehouse in Staten Island, New York, became the first to vote in favor of unionizing, and in 2021, a warehouse’s drive to organize a facility in Bessemer, Alabama, grabbed national attention, with politicians on both sides of the aisle, including Sens. Bernie Sanders (I-VT) and Marco Rubio (R-FL), supporting the push, albeit for different reasons.

Several factors have driven renewed interest in labor actions.

One reason places like Starbucks have become popular hotbeds of organizing is because organized labor has entered the public consciousness of the younger generation.

“My labor classes fill up, and they didn’t used to,” Bowling said of his classes at Duke.

The U.S. labor market has also been unusually hot and some employers have had serious problems with labor shortages coming out of the pandemic, particularly in 2021 and last year. Because of those shortages, workers could demand more from employers, such as higher wages, better working hours, and other concessions, without the fear of being laid off.

When workers have the leverage over companies, the environment is ripe for unionization efforts to flourish as workers flex their power.

Finally, unions might feel as though they have some cover to make these big asks and hold these strikes because they have allies in the executive branch. Biden has courted union and blue-collar support and can’t afford to lose it.

Another reason there has been so much attention all at once is more coincidental. These huge strikes, such as at UAW or Kaiser Permanente, where 75,000 healthcare workers recently went on strike, all don’t just happen out of the blue by dissatisfied unions. In order for a strike to be called, there has to be contract negotiations and an expiring contract — and contracts usually last for years.

In the past three years, some of the country’s biggest companies have coincidentally had their contracts expire around the same time. Couple that with a strong labor market and a union-friendly executive branch and you have a recipe for major attention and strikes, according to Bowling.

“Unions are more in the public consciousness, you have a tight labor market, you do have a Democrat in the White House … you have a friendly National Labor Relations Board who might help resolve the nature of some of these strikes … so we’ve got a little bit of a perfect storm coming together here,” Bowling said.

Still, despite the attention and headline-grabbing strikes and negotiations, private union membership has trended down in recent years. The private union membership rate fell to 6% last year, according to the Bureau of Labor Statistics. That is down from 6.1% in 2021 and 8.2% in 2003.

Still, the attention and strikes have been effective for unions in some cases. Just on Friday, Fain announced that “significant progress” has been made in talks with the “Big Three” automakers.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Fain said Ford has agreed to 23% wage hikes for workers, a number that is getting closer to the union’s demands, while GM and Stellantis were trailing Ford at 20%. The union boss said his union would keep pushing to get a historic contract with the automakers.

“It’s not about theatrics. It’s about power,” he said on Friday. “The power we have as working-class people. We’ve shown the Big Three that we’re not afraid to use it. And we’ve shown the Big Three that we are ready for a record contract when they are.”