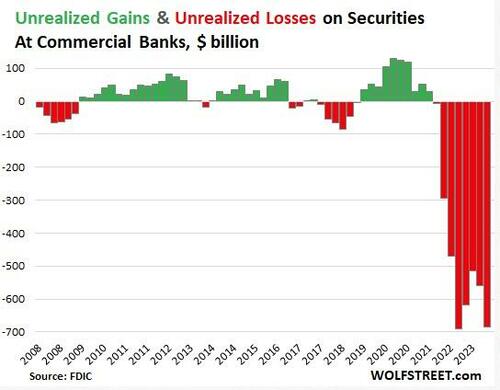

Unrealized losses on securities held by US banks exploded by 22% in the third quarter.

Of course, unrealized losses don’t really matter — until they do.

This is yet more evidence that the financial crisis that kicked off last March continues to bubble under the surface.

Unrealized losses, primarily on US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities rose by $126 billion in Q3 and now total $684 billion, according to the FDIC’s quarterly bank data release.

Current unrealized losses are only slightly below the record set in the third quarter of 2022. This reflects the fact that the FDIC took over three failed banks earlier his year and ate their unrealized losses when it sold the banks’ assets, thus wiping them from the books.

Unrealized looses on securities are divided between two accounting methods.

-

Unrealized losses on held-to-maturity (HTM) securities jumped by $81 billion to $391 billion.

-

Unrealized losses on available-for-sale (AFS) securities jumped by $45 billion to $293 billion.

It’s important to understand these are only paper losses. Ostensibly, the banks will hold these bonds until maturity and then will be paid their face value. If it plays out this way, there won’t be any real losses.

The problem is that these unrealized losses drastically decrease a bank’s liquidity. If it has to sell bonds in order to raise capital, the bank will experience significant losses. This is exactly what took down Silicon Valley Bank last March.

Here’s what happened.

SVB sold a large portion of its bond portfolio at a $1.8 billion loss. At the time, SVB CEO Greg Becke said the bank made the sale “because we expect continued higher interest rates, pressured public and private markets, and elevated cash burn levels from our clients.”

The bank bought the bonds when interest rates were low. As a result, the $21 billion available for sale (AVS) bond portfolio was not yielding above cash burn. Meanwhile, rising interest rates caused the value of the portfolio to fall significantly. The plan was to sell the longer-term, lower-interest-rate bonds and reinvest the money into shorter-duration bonds with a higher yield. Instead, the sale dented the bank’s balance sheet and caused worried depositors to pull funds out of the bank.

WolfStreet explained more generally how these “irrelevant” unrealized losses can suddenly become relevant.

Banks, via a quirk in bank regulations, don’t have to mark these securities to market value, but can carry them at purchase price. The difference between market value and purchase price is the ‘unrealized gain or loss’ that the bank must disclose in its quarterly financial filings, so that we the depositors can see them and get spooked by them and yank our money out, us billionaires and centimillionaires first, on the two fundamental principles of investing: 1, he who panics first, panics best; and 2, after us the deluge.”

The Federal Reserve set up a bailout program to allow banks to deal with this problem. Instead of selling bonds at a loss, cash-strapped banks can go to the Fed’s Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) and borrow against them “at par” (face value). This allows banks to use these undervalued assets to raise cash (at least temporarily) without realizing big losses on their balance sheets.

As unrealized losses rise, banks continue to tap into this bailout program more than nine months after the crisis kicked off.

Total outstanding loans in the BTFP program jumped by just over $5 billion in November alone.

In effect, the Fed managed to paper over the financial crisis with this bailout program.

It basically slapped a bandaid on it. But it has not addressed the underlying issue – the impact of rising interest rates on an economy and financial system addicted to easy money.

Unrealized losses on securities held by US banks exploded by 22% in the third quarter.

Of course, unrealized losses don’t really matter — until they do.

This is yet more evidence that the financial crisis that kicked off last March continues to bubble under the surface.

Unrealized losses, primarily on US Treasuries and mortgage-backed securities rose by $126 billion in Q3 and now total $684 billion, according to the FDIC’s quarterly bank data release.

Current unrealized losses are only slightly below the record set in the third quarter of 2022. This reflects the fact that the FDIC took over three failed banks earlier his year and ate their unrealized losses when it sold the banks’ assets, thus wiping them from the books.

Unrealized looses on securities are divided between two accounting methods.

It’s important to understand these are only paper losses. Ostensibly, the banks will hold these bonds until maturity and then will be paid their face value. If it plays out this way, there won’t be any real losses.

The problem is that these unrealized losses drastically decrease a bank’s liquidity. If it has to sell bonds in order to raise capital, the bank will experience significant losses. This is exactly what took down Silicon Valley Bank last March.

Here’s what happened.

SVB sold a large portion of its bond portfolio at a $1.8 billion loss. At the time, SVB CEO Greg Becke said the bank made the sale “because we expect continued higher interest rates, pressured public and private markets, and elevated cash burn levels from our clients.”

The bank bought the bonds when interest rates were low. As a result, the $21 billion available for sale (AVS) bond portfolio was not yielding above cash burn. Meanwhile, rising interest rates caused the value of the portfolio to fall significantly. The plan was to sell the longer-term, lower-interest-rate bonds and reinvest the money into shorter-duration bonds with a higher yield. Instead, the sale dented the bank’s balance sheet and caused worried depositors to pull funds out of the bank.

WolfStreet explained more generally how these “irrelevant” unrealized losses can suddenly become relevant.

Banks, via a quirk in bank regulations, don’t have to mark these securities to market value, but can carry them at purchase price. The difference between market value and purchase price is the ‘unrealized gain or loss’ that the bank must disclose in its quarterly financial filings, so that we the depositors can see them and get spooked by them and yank our money out, us billionaires and centimillionaires first, on the two fundamental principles of investing: 1, he who panics first, panics best; and 2, after us the deluge.”

The Federal Reserve set up a bailout program to allow banks to deal with this problem. Instead of selling bonds at a loss, cash-strapped banks can go to the Fed’s Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) and borrow against them “at par” (face value). This allows banks to use these undervalued assets to raise cash (at least temporarily) without realizing big losses on their balance sheets.

As unrealized losses rise, banks continue to tap into this bailout program more than nine months after the crisis kicked off.

Total outstanding loans in the BTFP program jumped by just over $5 billion in November alone.

In effect, the Fed managed to paper over the financial crisis with this bailout program.

It basically slapped a bandaid on it. But it has not addressed the underlying issue – the impact of rising interest rates on an economy and financial system addicted to easy money.

Loading…