Last week, Halliburton Co.'s CEO Jeff Miller warned hydraulic fracturing equipment is in short supply and could hamper fracking growth. Another oil/gas executive echoed the same warning this week and said bottlenecks could persist through 2023.

"Availability of frac fleets is one of main bottlenecks impeding oil and natural as production growth for the next 18 months," Robert Drummond, chief executive officer of fracking firm NexTier Oilfield Solutions, told Reuters.

Besides supply chain snarls, Drummond warned that capital constraints would make adding equipment to fields challenging. He said this imbalance could take several years to correct, adding that NexTier has no plans to expand fracking capacity this year.

This development is another setback for the Biden administration's efforts to increase US oil production to ease the worst inflation in forty years ahead of the midterm elections in November.

US crude production is around 11.6 million barrels per day, below the pre-pandemic 12.3 million bpd in 2019, the latest data from the Energy Information Administration show.

Matt Hagerty, a senior analyst at BTU Analytics, pointed out that "frac crew bottlenecks" are a "significant headwind for US producers headed into 2023." He said frac sand and labor shortages, elevated inflation, and limited frac fleets are a "perfect storm."

Halliburton's Miller said oil companies didn't have enough fracking equipment for newly leased wells. He said diesel-powered and electric equipment are in short supply, "making it almost impossible to add incremental capacity this year."

A similar message was conveyed by Exxon Mobil, whose CEO said that global oil markets might remain tight for three to five years primarily because of a lack of investment since the pandemic began.

Exxon CEO Darren Woods said it'll take time for oil firms to "catch up" on the investments needed to ensure enough supply.

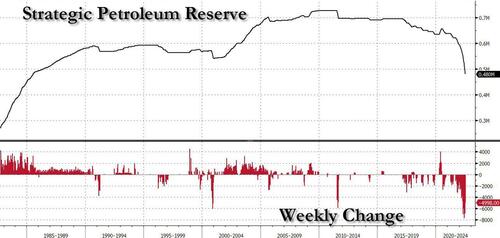

In response to shale's dismal ramp-up in production, the Biden administration has panic sold millions and millions of barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which has been drained by 125 million barrels so far in 2022 -- all in hopes of lowering gasoline prices at the pump ahead of the midterm elections in November.

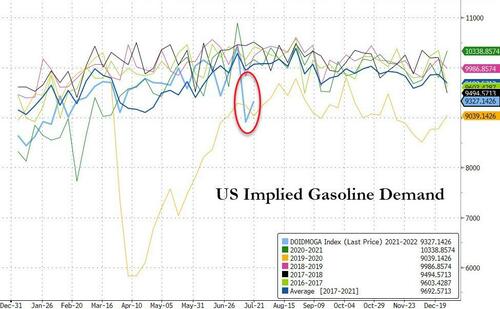

The good news is the recession, and high inflation appears to have sparked the weakest gasoline demand since 2013.

The Shale patch has a structural bottleneck that won't be resolved this year. Blame years of divestment and decarbonization for the mess.

Last week, Halliburton Co.’s CEO Jeff Miller warned hydraulic fracturing equipment is in short supply and could hamper fracking growth. Another oil/gas executive echoed the same warning this week and said bottlenecks could persist through 2023.

“Availability of frac fleets is one of main bottlenecks impeding oil and natural as production growth for the next 18 months,” Robert Drummond, chief executive officer of fracking firm NexTier Oilfield Solutions, told Reuters.

Besides supply chain snarls, Drummond warned that capital constraints would make adding equipment to fields challenging. He said this imbalance could take several years to correct, adding that NexTier has no plans to expand fracking capacity this year.

This development is another setback for the Biden administration’s efforts to increase US oil production to ease the worst inflation in forty years ahead of the midterm elections in November.

US crude production is around 11.6 million barrels per day, below the pre-pandemic 12.3 million bpd in 2019, the latest data from the Energy Information Administration show.

Matt Hagerty, a senior analyst at BTU Analytics, pointed out that “frac crew bottlenecks” are a “significant headwind for US producers headed into 2023.” He said frac sand and labor shortages, elevated inflation, and limited frac fleets are a “perfect storm.”

Halliburton’s Miller said oil companies didn’t have enough fracking equipment for newly leased wells. He said diesel-powered and electric equipment are in short supply, “making it almost impossible to add incremental capacity this year.”

A similar message was conveyed by Exxon Mobil, whose CEO said that global oil markets might remain tight for three to five years primarily because of a lack of investment since the pandemic began.

Exxon CEO Darren Woods said it’ll take time for oil firms to “catch up” on the investments needed to ensure enough supply.

In response to shale’s dismal ramp-up in production, the Biden administration has panic sold millions and millions of barrels of oil from the Strategic Petroleum Reserve, which has been drained by 125 million barrels so far in 2022 — all in hopes of lowering gasoline prices at the pump ahead of the midterm elections in November.

The good news is the recession, and high inflation appears to have sparked the weakest gasoline demand since 2013.

The Shale patch has a structural bottleneck that won’t be resolved this year. Blame years of divestment and decarbonization for the mess.