A few years ago, you would have unfolded your newspaper and read opinion and analysis like this.

Those days are gone.

As Visual Capitalist's Avery Koop details below, most people today - more than 8 in 10 Americans - get their news via digital devices, doing their reading on apps, listening to podcasts, or scrolling through social media feeds.

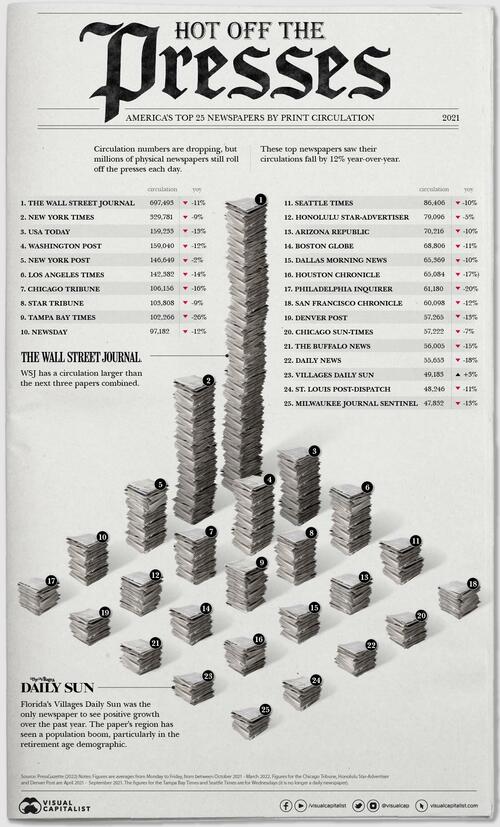

It’s no surprise then that over the last year, only one U.S. newspaper of the top 25 most popular in the country saw positive growth in their daily print circulations.

Based on data from Press Gazette, this visual stacks up the amount of daily newspapers different U.S. publications dole out and how that’s changed year-over-year.

Extra, Extra – Read All About It

The most widely circulated physical newspaper is the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) by a long shot - sending out almost 700,000 copies a day. But it is important to note that this number is an 11% decrease since 2021.

These papers, although experiencing negative growth when it comes to print, are still extremely popular and widely-read publications digitally—not only in the U.S., but worldwide. For example, the New York Times reported having reached 9 million subscribers globally earlier this year.

The one paper with increased print circulation was The Villages Daily Sun, which operates out of a retirement community in Florida. Elderly people tend to be the most avid readers of print papers. Another Florida newspaper, the Tampa Bay Times, was the worst performer at -26%.

In total, 2,500 U.S. newspapers have shut down since 2005. One-third of American newspapers are expected to be shuttered by 2025. This particularly impacts small communities and leaves many across America in ‘news deserts.’

The decline is relentless. Print papers are losing one out of eight subscribers every year. Their daily circulation, over 63 million at its peak in the 1980s, is now about one-third that size. Over 25% of all American newspapers have died in the past 15 years.

As Charles Lipson observes at RealClearPolitics.com, some observers, especially conservative ones, have cast a skeptical eye on this contemporary media landscape and blamed the decline of print publications on “woke” newsrooms. They are mistaking the cart for the horse. It’s true that most newsrooms are woke, woke, woke. So are elite law firms, consulting firms, social media giants, entertainment companies, advertising firms, university faculty, and so on. Their employees, having completed their ideological training at places like Harvard, Brown, and Oberlin, tell us their pronouns in every email and wonder if Bernie Sanders might be too moderate. They dominate today’s journalism, and their dominance is reflected in their papers’ content.

In a country that is evenly split between left and right, that tilt leaves a lot of readers unhappy, and some have undoubtedly dropped their subscriptions. Some papers also died during the pandemic, though most were already facing bleak futures. But the coronavirus and ideological bias are not the main reasons why print papers are on the road to oblivion. They are on that road because technological innovation devastated their old business model.

This technological shift actually encourages newsroom bias. Why? Because, as online sites proliferate, readers can easily gravitate to those that reflect their views. This self-selection reinforces the sites’ incentives to tailor their content to keep those users and attract more like-minded ones.

In this segmented market, with lots of different niches, news organizations pick their target audience. For MSNBC, that audience is progressive. The channel wants to attract more of them, not challenge their views or garner a few conservatives. By contrast, PJ Media is trying to reach more conservatives, not futilely chasing progressives. That’s Marketing 101. The problem for journalism is that this “niche” logic has distorted general-interest papers, like the Los Angeles Times. It gives free rein to ideological bias among reporters and editors, muddling their editorial perspective with “hard news” coverage.

The logic behind this bias is powerful. All of us are attracted to sites that confirm our views and buttress them with friendly content. Social scientists call it “confirmation bias.” Now that we have so many alternative news sources, that bias drives our choices, from CNN to Fox News. And it drives those outlets to produce content their viewers find ideologically appealing, not challenging. There are some exceptions, of course, like RealClearPolitics, which aggregates and produces opinion pieces from left, right, and center and hires reporters to write the news of day straight. But this even-handedness is rare. Most outlets have slipped into comfortable ideological niches.

The result is landscape littered with “news silos,” each appealing to its chosen market segment. The social and political effects are far-reaching. As news consumers, we have more options than ever (good), but we are increasingly insulated from opposing views (bad). The days of general-interest local papers like the Memphis Commercial-Appeal are gone. Those of big-city papers like the Chicago Tribune are fading fast. We are hunkering down in our silos, where never is heard a discouraging word, at least not about “our side.” This insularity is bound to deepen our country’s ideological divide. That’s very bad news indeed.

A few years ago, you would have unfolded your newspaper and read opinion and analysis like this.

Those days are gone.

As Visual Capitalist’s Avery Koop details below, most people today – more than 8 in 10 Americans – get their news via digital devices, doing their reading on apps, listening to podcasts, or scrolling through social media feeds.

It’s no surprise then that over the last year, only one U.S. newspaper of the top 25 most popular in the country saw positive growth in their daily print circulations.

Based on data from Press Gazette, this visual stacks up the amount of daily newspapers different U.S. publications dole out and how that’s changed year-over-year.

Extra, Extra – Read All About It

The most widely circulated physical newspaper is the Wall Street Journal (WSJ) by a long shot – sending out almost 700,000 copies a day. But it is important to note that this number is an 11% decrease since 2021.

These papers, although experiencing negative growth when it comes to print, are still extremely popular and widely-read publications digitally—not only in the U.S., but worldwide. For example, the New York Times reported having reached 9 million subscribers globally earlier this year.

The one paper with increased print circulation was The Villages Daily Sun, which operates out of a retirement community in Florida. Elderly people tend to be the most avid readers of print papers. Another Florida newspaper, the Tampa Bay Times, was the worst performer at -26%.

In total, 2,500 U.S. newspapers have shut down since 2005. One-third of American newspapers are expected to be shuttered by 2025. This particularly impacts small communities and leaves many across America in ‘news deserts.’

The decline is relentless. Print papers are losing one out of eight subscribers every year. Their daily circulation, over 63 million at its peak in the 1980s, is now about one-third that size. Over 25% of all American newspapers have died in the past 15 years.

As Charles Lipson observes at RealClearPolitics.com, some observers, especially conservative ones, have cast a skeptical eye on this contemporary media landscape and blamed the decline of print publications on “woke” newsrooms. They are mistaking the cart for the horse. It’s true that most newsrooms are woke, woke, woke. So are elite law firms, consulting firms, social media giants, entertainment companies, advertising firms, university faculty, and so on. Their employees, having completed their ideological training at places like Harvard, Brown, and Oberlin, tell us their pronouns in every email and wonder if Bernie Sanders might be too moderate. They dominate today’s journalism, and their dominance is reflected in their papers’ content.

In a country that is evenly split between left and right, that tilt leaves a lot of readers unhappy, and some have undoubtedly dropped their subscriptions. Some papers also died during the pandemic, though most were already facing bleak futures. But the coronavirus and ideological bias are not the main reasons why print papers are on the road to oblivion. They are on that road because technological innovation devastated their old business model.

This technological shift actually encourages newsroom bias. Why? Because, as online sites proliferate, readers can easily gravitate to those that reflect their views. This self-selection reinforces the sites’ incentives to tailor their content to keep those users and attract more like-minded ones.

In this segmented market, with lots of different niches, news organizations pick their target audience. For MSNBC, that audience is progressive. The channel wants to attract more of them, not challenge their views or garner a few conservatives. By contrast, PJ Media is trying to reach more conservatives, not futilely chasing progressives. That’s Marketing 101. The problem for journalism is that this “niche” logic has distorted general-interest papers, like the Los Angeles Times. It gives free rein to ideological bias among reporters and editors, muddling their editorial perspective with “hard news” coverage.

The logic behind this bias is powerful. All of us are attracted to sites that confirm our views and buttress them with friendly content. Social scientists call it “confirmation bias.” Now that we have so many alternative news sources, that bias drives our choices, from CNN to Fox News. And it drives those outlets to produce content their viewers find ideologically appealing, not challenging. There are some exceptions, of course, like RealClearPolitics, which aggregates and produces opinion pieces from left, right, and center and hires reporters to write the news of day straight. But this even-handedness is rare. Most outlets have slipped into comfortable ideological niches.

The result is landscape littered with “news silos,” each appealing to its chosen market segment. The social and political effects are far-reaching. As news consumers, we have more options than ever (good), but we are increasingly insulated from opposing views (bad). The days of general-interest local papers like the Memphis Commercial-Appeal are gone. Those of big-city papers like the Chicago Tribune are fading fast. We are hunkering down in our silos, where never is heard a discouraging word, at least not about “our side.” This insularity is bound to deepen our country’s ideological divide. That’s very bad news indeed.