(function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v3.0”; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’)); –>

–>

August 2, 2023

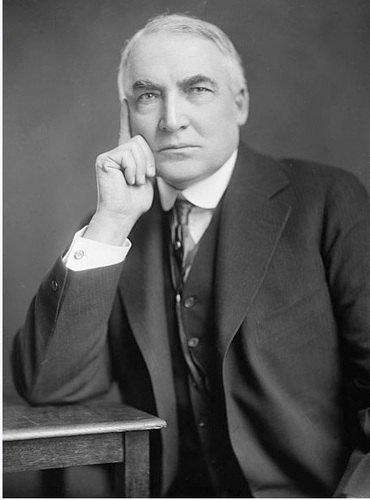

Today marks the one hundredth anniversary of the death of Warren Gamaliel Harding, a man almost universally identified as one of the worst Presidents ever. In truth, Harding was not nearly as bad as history has treated him. Writers like Ryan S. Walters (in his recent book Harding: The Jazz Age President) have made well-researched efforts to demonstrate that Harding’s administration was actually a successful model of conservatism.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”); } }); }); }

The established narrative goes something like this: Harding, a likeable but dull and unimaginative newspaper publisher from Marion, Ohio, runs for the Ohio legislature at the behest of local Republicans and is elected to the state senate. There he meets a political Svengali named Harry Daugherty, who sees Harding as his ticket to bigger and better things. With Daugherty’s help, Harding wins election to the U.S. Senate in 1914 and serves an undistinguished and ineffective term.

The established narrative goes something like this: Harding, a likeable but dull and unimaginative newspaper publisher from Marion, Ohio, runs for the Ohio legislature at the behest of local Republicans and is elected to the state senate. There he meets a political Svengali named Harry Daugherty, who sees Harding as his ticket to bigger and better things. With Daugherty’s help, Harding wins election to the U.S. Senate in 1914 and serves an undistinguished and ineffective term.

At the 1920 Republican National Convention, Daugherty employs Machiavellian tactics in a smoke-filled room to get Harding nominated as the Republican Presidential candidate. Harding runs a campaign full of platitudes like “normalcy” but devoid of vision, but nevertheless wins in a landslide. Once in office, Harding spends his time playing golf and poker and cavorting with his mistress, leaving Daugherty and others to run the government; they proceed to loot everything. When Harding finds out, he is so overwhelmed by guilt that he suffers a fatal stroke, leaving Calvin Coolidge (another conservative President despised by the Left) to clean up the mess.

As Walters points out, the facts about Harding are very different. Harding was no political neophyte or dilettante when he arrived in Washington: He had long been interested in politics, serving as a delegate to the Republican National Convention in 1888, when he was not yet twenty-three. He served two terms in the Ohio senate and ended his tenure there as Republican floor leader; he then served a term as Ohio’s lieutenant governor before being elected to the U. S. Senate[i].

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”); } }); }); }

As a first-term Senator, he had no leadership role; however, he served on the Foreign Relations Committee and was an ally of committee chairman Henry Cabot Lodge. Therefore, Harding was in the vanguard of senators who fought the ratification of the Treaty of Versailles and the approval of the League of Nations.[ii] Although Harding at first was in favor of the treaty (he later changed his mind and voted against it), his opposition to the League earned him Woodrow Wilson’s enmity (it was Wilson who first accused Harding of having a “disturbingly dull mind”[iii]) and the wrath of progressives to the present day.[iv]

The facts surrounding the 1920 Republican convention also need to be reviewed. Harding was not an unknown factor when the Republicans met in Chicago for their 1920 convention; he had declared his candidacy for the nomination the previous December but had not secured many delegates during the primaries. When the convention became deadlocked, party leaders met in the now-famous smoke-filled room to discuss breaking the logjam. They agreed that the front-runners each had too much baggage and had offended too many delegates to secure the nomination, so the leaders agreed to promote Harding as a candidate who could be supported by all factions of the party. Once he had their backing, Harding secured the nomination.[v]

Upon assuming the Oval Office, Harding inherited a nation in turmoil. The economy was in shambles. The Federal income tax, which Wilson had established (through constitutional amendment) on the promise that it would only apply to the wealthy, was affecting people at all wage levels.[vi] Wartime Federal spending had continued unabated, and the country was deeply in debt. The inflation-fueled postwar boomlet had petered out, leaving the country mired in a depression.[vii] Harding’s first order of business was to get the economy moving again.

With the help of Treasury Secretary Andrew Mellon and budget director Charles Dawes, Harding embarked on an economic program that Ronald Reagan would have envied. Harding pushed tax cuts through Congress, cut the size of the Federal budget, and vetoed spending bills that he deemed unnecessary – even if he was sympathetic to their aims.[viii] He also increased tariffs to protect American farmers and manufacturers.[ix] The economy staged one of the biggest turnarounds in history as a result – and the prosperity continued through the end of the decade, which is still referred to as “the roaring Twenties.”

While Harding took a first-things-first approach to the economy, he believed that his most important duty as President was to heal the nation’s psyche. The Spanish flu epidemic had killed millions and had weakened the country’s mood. More pressing were the effects of the Bolshevik Revolution in Russia and Vladimir Lenin’s pledge to take communism to the world. That resulted in the country’s first “Red scare” as leftist radicals began acts of terrorism throughout America. Wilson, a die-hard Southern racist, saw Black Americans (especially those returning from World War I) as especially vulnerable to communist propaganda and targeted them as scapegoats, which led to a resurgence of groups like the Ku Klux Klan and lynchings[x].

Harding favored the arrest of those who committed violence, but he was horrified at the terror unleashed on Black people. He had been sympathetic to Blacks even as a child, so much so that he was often accused of having Black blood (his father-in-law, who despised Harding, even called him the n-word).[xi] Harding pushed for equal educational and economic opportunities for Black people, and made it clear he was their ally. He was the first President to urge passage of a Federal anti-lynching law. He also reached out to Jews and Native Americans, and had sympathy for working people.[xii]

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”); } }); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Harding’s efforts to heal the nation sometimes took political courage. He commuted the prison sentence of socialist Eugene V. Debs, whom Wilson had imprisoned under the Espionage Act for speaking against the war. Harding did so, believing it the right thing to do, even though many of his supporters (including Mrs. Harding) opposed it. While Debs was no fan of Harding’s politics, he was eternally grateful for the gesture and called Harding a kind, humane man.[xiii] In another act of political valor, he traveled to segregated Alabama and delivered an address supporting economic equality and opportunity for Black Americans.[xiv]

Then there were the scandals. Harding’s Cabinet included many honest, capable men: Mellon at Treasury; Dawes at OMB; Herbert Hoover at Commerce; Charles Evans Hughes at State; Will Hays as Postmaster General. But others in his administration (including Daugherty, who had been appointed Attorney General) saw an opportunity to enrich themselves. Edmund Starling, head of Harding’s Secret Service detail, wrote that Harding’s downfall came from trusting everyone, and that “a few of his friends did not hold him in the high regard that he held them.”[xv] But as Walters notes, when Harding had evidence of wrongdoing, he acted.

One situation involved Charles Forbes, head of the Veterans Bureau, who skimmed money from construction projects and took bribes. When Harding learned of it, he was so furious that he confronted Forbes physically and began choking him before demanding Forbes’s resignation. (Forbes was later convicted and spent two years in prison.) Another involved Jess Smith, who was Daugherty’s bagman in accepting bribes in exchange for access to the Administration. Harding summoned Smith to the White House, demanded his resignation, and told him that he would be arrested in the morning. Smith went home and committed suicide. (Daugherty was forced to resign by Coolidge; although tried twice for wrongdoing, he was never convicted.)[xvi]

The most famous scandal was Teapot Dome, perpetrated by Harding’s Senate friend Albert Fall, who had been appointed Interior Secretary. Fall leased oil reserves meant for the Navy to oil companies in exchange for “loans” that were never repaid. (Fall was later convicted and spent time in prison.)[xvii] The betrayals by Daugherty and Fall, the men closest to Harding, are likely what led to Harding’s fatal stroke. However, none of the financial misdeeds of the guilty have ever been traced to Harding himself.

Walters also refutes the image of Harding as a notorious womanizer. He concedes that while he fathered a child with Nan Britton (DNA evidence confirmed it), he contends that Britton’s salacious book about trysts with Harding in the White House are contradicted by witnesses who contend that none of it happened. (Britton had to publish the book herself because no reputable publisher would touch it.)[xviii] Walters also concedes that Harding may have had an affair while still in Marion, but insists that was the extent of his adultery.[xix]

Walters is but the latest author to reconsider Harding; he cites others who are also taking another look at our 29th President[xx]. They are undoing the work started by people like publisher William Allen White (Harding’s nemesis) and Alice Roosevelt Longworth, who saw Harding’s conservatism as undermining her father’s progressive legacy. We all should give Warren Harding the respect he is really due.

The one duty we owe to history is to rewrite it.

[i] Walters, Ryan S., Harding: The Jazz Age President, Regnery History (2023), pages 58-59.

[v] Id. at 50-51.

[ix] Id. at 109-110.

[xx] Id. at xv-xxvii.

<!–

–>

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>