–>

August 4, 2022

According to Patrick Basham, there are such things as “non-polling metrics” — things like comparative party registrations, turnouts in the primary elections, social media followings, attendance at campaign rallies and other measures that had, prior to the 2020 presidential election, predicted the outcome of presidential elections with 100% accuracy. In 2020, all these measures pointed to a Trump victory. In attendance at campaign rallies, for example, Trump’s average attendance exceeded Biden’s by a average ratio of 343 to 1. And yet Biden won.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

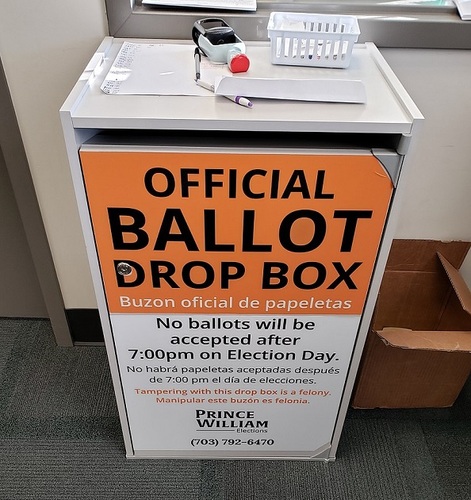

There were other anomalies: “…Biden could win only one of the 19 battleground counties around the U.S., but he supposedly won all of the battleground states.” And there were hundreds of affidavits charging malfeasance, and there were whistleblowers in Pennsylvania and Georgia. There were audits in Arizona and Montana showing potential fraud. And, most recently, there was True the Vote/Dinesh D’Souza’s documentary 2000 Mules, which, through cell-phone geo-tracking and surveillance videotapes, showed persons, often in the dead of night, apparently stuffing ballot drop boxes.

None of these, at least so far, have been sufficient evidence for bring a charge of vote fraud against specific individuals. But, the assurances of Democrats, major media and others notwithstanding, they certainly cast legitimate doubt on the integrity of the 2020 election.

In the face of such grounds for doubt, do we, with regard to future elections, really need to prove that the 2020 election was in fact stolen? In order to take remedial action, shouldn’t it be enough to prove that it (and others) could have been stolen?

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Indeed, should we even need to do that? Shouldn’t we, simply as a matter of course, have the most secure system possible, so secure that doubts do not even arise?

That is, in fact, is what Article 4, §4 of the Constitution — the Guarantee Clause — asserts:

“The United States shall guarantee to every State in this Union a Republican Form of Government… [that is, one ruled with the consent of the people].”

Obviously, a government that rules by means of vote fraud does not rule with the consent of the people. And the clause requires no reasonable grounds for suspicion before its guarantee is activated. It is eternally activated.

Of course, neither the United States, nor any earthly authority, can actually “guarantee” that no state will be subverted by vote fraud. All it can guarantee is that it will take every step to ensure that such an insidious, contemptible crime does not occur.

In fact, all steps have not been taken. And we did not need the 2020 election to tell us that. A variety of vulnerabilities, including absentee voting, were addressed in 2004 in John Fund’s book, Stealing Elections. How Voter Fraud Threatens our Democracy. With respect to absentee voting, a 2005 commission on federal election reform — co-chaired by former President Jimmy Carter and former Secretary of State James Baker III identified absentee ballots as “the largest source of potential voter fraud.” And in 2012, again on postal voting, Adam Liptak of the New York Times wrote:

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

“Voting by mail is now common enough and problematic enough that election experts say there have been multiple elections in which no one can say with confidence which candidate was the deserved winner.”

Despite such warnings, we have not restricted mail-in voting to only those for whom it is necessary and requested, but have extended it to those for  whom it is neither necessary nor requested. The stated rationale is that such voting is more convenient, and so increases turnout, and the more turnout, the better. The first and second parts of that rationale are true, the third — apparently premised on the idea that one votes simply to promote his/her own self-interest — is debatable at best.

whom it is neither necessary nor requested. The stated rationale is that such voting is more convenient, and so increases turnout, and the more turnout, the better. The first and second parts of that rationale are true, the third — apparently premised on the idea that one votes simply to promote his/her own self-interest — is debatable at best.

In any case, if mail-in such voting also increases voter fraud, then other effects are irrelevant. The Constitution guarantees election integrity, not convenience or turnout.

Under it, either Congress or, (through a Constitutional challenge) the Supreme Court could act. Of course, individuals in either of these institutions may be beholden to voter fraud efforts themselves. Of the two, however, it is certainly Congress members who would be the more vulnerable.

And while Congress members would certainly be more answerable to the people, it is not the legislative, but the judicial process — one in which the opposing arguments are refined, distilled, and made public — that actually provides the most definitive answer — which would make it the preferable option.

If our ballots were not secret, it would be easy to prove vote fraud after the fact. All a voter would have to do is check the public record to see if his or her vote were recorded correctly. But, for good reason, our votes are not public, and, if they are falsely cast or are not counted, there is, after the fact, no way of proving it.

In a case challenging unnecessary mail-in voting, the plaintiff would not have to prove that compared to in-person voting, mail-in voting was more vulnerable to fraud; conversely, the defendant state would have to prove that it was not.

Certainly, federal courts would have jurisdiction over such an issue. But, what about the states? While there appears to be no state constitution that expressly “guarantees” that the state would be ruled only by the consent of the governed, many if not all are premised on that proposition.

For example, Art. 1, Sect. 1 of the Wisconsin Constitution reads:

All people are born equally free and independent, and have certain inherent rights… to secure these rights, governments are instituted, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed.

If all the laws of the state are presumed to be enacted with the consent of the governed, and that fact itself comes into question, does the state court have jurisdiction to address such an issue? The Wisconsin Constitution doesn’t expressly assert such jurisdiction, but if the court does not have it, and the legislature itself has been corrupted by voter fraud, then what remedy is there?

Assuming that plaintiff/petitioners bring such issue to the courts, they would not have the luxury of conceding the 2022 elections to potential voter fraud while the legal process unfolds. For if such fraud occurs, and Democrats gain an operational majority in Congress, they have told us what, through “election reform,” they will do: federalize elections, require the option of discretionary mail-in voting and of ballot harvesting, and effectively eliminate the requirement for voter IDs. In separate measures, they would end in the filibuster and pack the Supreme Court.

In such case, there could be no confidence in the integrity of the federalized elections, and no remedy for it. To eliminate the possibility that we arrive at such a scenario by means of unnecessary mail-in voting — the very kind of voting that would be being challenged — the courts should issue an injunction against such voting until its constitutionality is legally resolved.

If we are to ensure honest elections, 2023 may be too late. The time to act is now.

Image: Bryan Alexander

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>