Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

All of these are structural dynamics that won't go away in a few months or years.

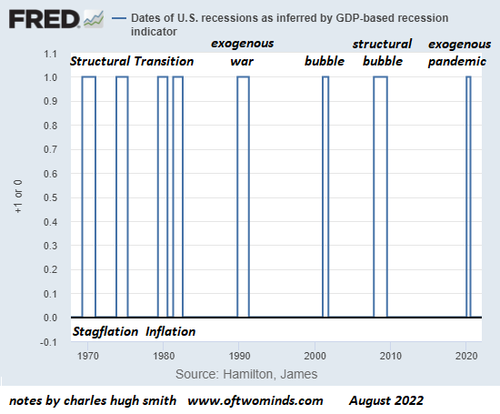

Let's explore what's different now compared to recessions of the past 60 years.

1. Deglobalization is inflationary. Offshoring production to low-cost countries imported deflation (product prices remained flat or declined) and boosted corporate profits.

Deglobalization will increase costs and pressure profits.

Just as cleaning up the environmental damage of rampant industrialization imposed costs on the U.S. economy in the 1970s that generated stagflation (inflation and stagnant growth), reshoring essential supply chains will impose costs, pushing prices higher.

Everything costs more in developed economies due to their high wages and social costs (pensions, healthcare, disability, etc.), high taxes, strict environmental standards and extensive regulations.

Consumers will pay more as supply chains are onshored / secured.

2. Energy will cost more. The price of oil and natural gas will fluctuate and could drop significantly as global demand drops, but in the long run the easy-to-access energy has been depleted and all energy will cost more.

Consumers will pay more regardless of where the goods and services come from.

3. Capital will no longer have zero cost: interest rates may briefly return to near-zero but over time the cost of credit/borrowing will rise.

The 40+ year cycle of credit has bottomed and is reversing. As global risks rise, capital will demand a return.

Global risks are much higher than generally recognized. Each risk factor doesn't just add risk arithmetically: 1 + 1 + 1 = 3. Risk rises geometrically as each risk boosts the possibility of runaway feedback.

Climate change, scarcities, geopolitical tensions, capital flows--each reinforces the negative effects of the others. As risk rises, capital demands a higher return.

4. Definancialization will revalue assets. The hyper-financialization that fueled global growth for the past 40 years depended on the cost of credit falling: interest rates fell for 40 years, rewarding borrowers and buyers of bonds, which increased in value with each click down in interest rates.

These trends are reversing. Credit will cost more and every existing bond loses value with every click higher in interest rates / yields.

As profits from globalization dry up and credit costs rise, asset valuations based on cheap credit and rising profits will be repriced lower.

Assets that benefit from scarcity, Deglobalization and Definancialization may increase in value.

But there are many other factors that play a part in revaluing assets:

-

generational selling as the elderly sell assets to fund their retirement

-

global capital flows as money flees insecure Periphery nations for the Core (North America)

-

heightened risk will revalue whatever is deemed safe and secure and what's viewed as risky / speculative

-

unprecedented inequality will drive clawbacks, wealth taxes and expropriations of wealth viewed as illegitimate or excessive.

Any one of these factors could upend conventional expectations of what each asset class will do in the future. All four interacting makes it impossible to predict any future valuation with any certainty.

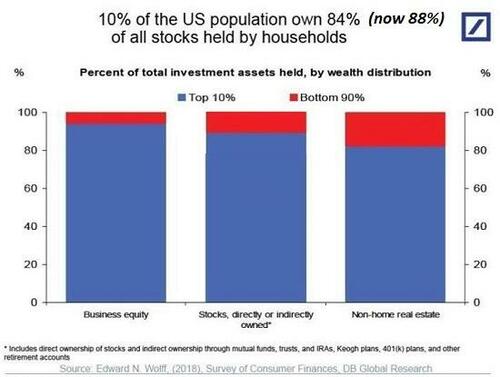

5. Wealth will take a hit, affecting the top 10% who own almost 90% of the wealth.

If history is any guide, all of the $400+ trillion in private wealth globally will not find a new home that preserves current valuations.

The losses will fall lightly on those who own few assets, i.e. the majority. The heavy losses will fall on those who own most of the assets--the top 5%.

This reverse wealth effect will reduce their ability to spend / consume, shrinking luxury / discretionary spending.

Demand for essentials will remain steady, demand for non-essentials will drop.

6. Labor scarcities will increase. Workforces in most nations are shrinking while the population of retirees' soars.

This undermines the entire social contract established in the postwar era (1950s and 1960s) which are all "pay as you go" programs that were designed for 4 or 5 workers supporting one retiree.

Now that the ratio has fallen to two workers (or less) to each retiree, the programs are unsustainable.

7. The unprecedented inequality of income and wealth has changed perceptions and values, changing societies in ways few recognize.

Young people with average jobs / income have no hope of affording a home, retirement or raising a family. So they've given up.

In China, it's called laying flat. In Japan, it has numerous manifestations, from Hikkomori (withdrawing from society) to arubaito (part-time work).

Since it's hopeless for average people to get all the good things with average effort, people give up and try to enjoy life without sacrificing themselves in the vain hope they'll somehow claw their way into the upper-middle class and be able to afford a family, house and retirement.

This is why pundits are complaining about lazy workers. Why aren't people working hard like they used to? because hard work is increasingly pointless. Just get by and enjoy life.

8. The pandemic changed perceptions of what's important. People gained new appreciation for the here and now and the futility of assuming the future is riskless and predictable.

Rather than sacrifice for an increasingly unstable, unpredictable future, people are pursuing what they want now.

For many younger people, this means ditching the dreams of wealth and conventional success for enjoying life in the here and now.

For those with incomes and assets, they're buying stuff they want now rather than putting it off. They're less concerned about debt. As long as they can swing the payments now, that's all that matters.

For others, work is optional. They found ways to get by without working. Now they may be lured back to work if the work is easy and they control their own schedule.

Employers are frustrated that they can't force employees to exclusively serve their needs.

As workers change what they consider important, this is forcing employers to pay attention to essential workers they took for granted.

9. Non-essential jobs will be slashed. Finding people to clean hotel rooms is hard, and so resorts are cutting services even as they jack up prices.

Enterprises can't cut maids, drivers, waiters, welders, etc., nor can these jobs be automated, despite the robotic fantasies of the intelligentsia.

Who they can cut are all the people spending their days in meetings.

10. Deglobalization will re-order mercantilist economies that have depended on exports for their bread and butter and consumer economies dependent on essentials imported from elsewhere.

Essentials (food, energy, technology) will increasingly be viewed (correctly) as national security priorities. Relying on other nations for essentials will be viewed (correctly) as increasing vulnerability and risk.

This will re-order all economies on a fundamental level. National security and trusted alliances will become higher priorities than increasing corporate profits.

All of these are structural dynamics that won't go away in a few months or years. They will transform the economy and society either positively (for those who embrace Degrowth) or negatively (those who cling to the bubble-dependent Waste Is Growth Landfill Economy).

* * *

My new book is now available at a 10% discount this month: When You Can't Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal. If you found value in this content, please join me in seeking solutions by becoming a $1/month patron of my work via patreon.com.

Authored by Charles Hugh Smith via OfTwoMinds blog,

All of these are structural dynamics that won’t go away in a few months or years.

Let’s explore what’s different now compared to recessions of the past 60 years.

1. Deglobalization is inflationary. Offshoring production to low-cost countries imported deflation (product prices remained flat or declined) and boosted corporate profits.

Deglobalization will increase costs and pressure profits.

Just as cleaning up the environmental damage of rampant industrialization imposed costs on the U.S. economy in the 1970s that generated stagflation (inflation and stagnant growth), reshoring essential supply chains will impose costs, pushing prices higher.

Everything costs more in developed economies due to their high wages and social costs (pensions, healthcare, disability, etc.), high taxes, strict environmental standards and extensive regulations.

Consumers will pay more as supply chains are onshored / secured.

2. Energy will cost more. The price of oil and natural gas will fluctuate and could drop significantly as global demand drops, but in the long run the easy-to-access energy has been depleted and all energy will cost more.

Consumers will pay more regardless of where the goods and services come from.

3. Capital will no longer have zero cost: interest rates may briefly return to near-zero but over time the cost of credit/borrowing will rise.

The 40+ year cycle of credit has bottomed and is reversing. As global risks rise, capital will demand a return.

Global risks are much higher than generally recognized. Each risk factor doesn’t just add risk arithmetically: 1 + 1 + 1 = 3. Risk rises geometrically as each risk boosts the possibility of runaway feedback.

Climate change, scarcities, geopolitical tensions, capital flows–each reinforces the negative effects of the others. As risk rises, capital demands a higher return.

4. Definancialization will revalue assets. The hyper-financialization that fueled global growth for the past 40 years depended on the cost of credit falling: interest rates fell for 40 years, rewarding borrowers and buyers of bonds, which increased in value with each click down in interest rates.

These trends are reversing. Credit will cost more and every existing bond loses value with every click higher in interest rates / yields.

As profits from globalization dry up and credit costs rise, asset valuations based on cheap credit and rising profits will be repriced lower.

Assets that benefit from scarcity, Deglobalization and Definancialization may increase in value.

But there are many other factors that play a part in revaluing assets:

-

generational selling as the elderly sell assets to fund their retirement

-

global capital flows as money flees insecure Periphery nations for the Core (North America)

-

heightened risk will revalue whatever is deemed safe and secure and what’s viewed as risky / speculative

-

unprecedented inequality will drive clawbacks, wealth taxes and expropriations of wealth viewed as illegitimate or excessive.

Any one of these factors could upend conventional expectations of what each asset class will do in the future. All four interacting makes it impossible to predict any future valuation with any certainty.

5. Wealth will take a hit, affecting the top 10% who own almost 90% of the wealth.

If history is any guide, all of the $400+ trillion in private wealth globally will not find a new home that preserves current valuations.

The losses will fall lightly on those who own few assets, i.e. the majority. The heavy losses will fall on those who own most of the assets–the top 5%.

This reverse wealth effect will reduce their ability to spend / consume, shrinking luxury / discretionary spending.

Demand for essentials will remain steady, demand for non-essentials will drop.

6. Labor scarcities will increase. Workforces in most nations are shrinking while the population of retirees’ soars.

This undermines the entire social contract established in the postwar era (1950s and 1960s) which are all “pay as you go” programs that were designed for 4 or 5 workers supporting one retiree.

Now that the ratio has fallen to two workers (or less) to each retiree, the programs are unsustainable.

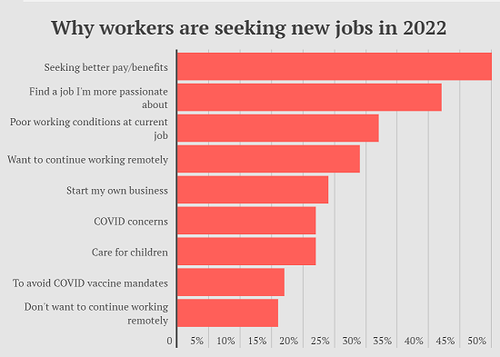

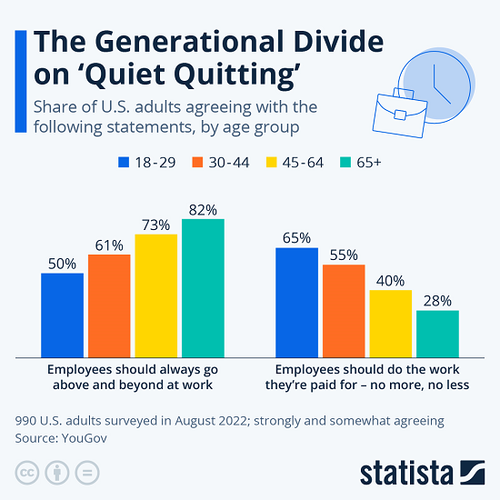

7. The unprecedented inequality of income and wealth has changed perceptions and values, changing societies in ways few recognize.

Young people with average jobs / income have no hope of affording a home, retirement or raising a family. So they’ve given up.

In China, it’s called laying flat. In Japan, it has numerous manifestations, from Hikkomori (withdrawing from society) to arubaito (part-time work).

Since it’s hopeless for average people to get all the good things with average effort, people give up and try to enjoy life without sacrificing themselves in the vain hope they’ll somehow claw their way into the upper-middle class and be able to afford a family, house and retirement.

This is why pundits are complaining about lazy workers. Why aren’t people working hard like they used to? because hard work is increasingly pointless. Just get by and enjoy life.

8. The pandemic changed perceptions of what’s important. People gained new appreciation for the here and now and the futility of assuming the future is riskless and predictable.

Rather than sacrifice for an increasingly unstable, unpredictable future, people are pursuing what they want now.

For many younger people, this means ditching the dreams of wealth and conventional success for enjoying life in the here and now.

For those with incomes and assets, they’re buying stuff they want now rather than putting it off. They’re less concerned about debt. As long as they can swing the payments now, that’s all that matters.

For others, work is optional. They found ways to get by without working. Now they may be lured back to work if the work is easy and they control their own schedule.

Employers are frustrated that they can’t force employees to exclusively serve their needs.

As workers change what they consider important, this is forcing employers to pay attention to essential workers they took for granted.

9. Non-essential jobs will be slashed. Finding people to clean hotel rooms is hard, and so resorts are cutting services even as they jack up prices.

Enterprises can’t cut maids, drivers, waiters, welders, etc., nor can these jobs be automated, despite the robotic fantasies of the intelligentsia.

Who they can cut are all the people spending their days in meetings.

10. Deglobalization will re-order mercantilist economies that have depended on exports for their bread and butter and consumer economies dependent on essentials imported from elsewhere.

Essentials (food, energy, technology) will increasingly be viewed (correctly) as national security priorities. Relying on other nations for essentials will be viewed (correctly) as increasing vulnerability and risk.

This will re-order all economies on a fundamental level. National security and trusted alliances will become higher priorities than increasing corporate profits.

All of these are structural dynamics that won’t go away in a few months or years. They will transform the economy and society either positively (for those who embrace Degrowth) or negatively (those who cling to the bubble-dependent Waste Is Growth Landfill Economy).

* * *

My new book is now available at a 10% discount this month: When You Can’t Go On: Burnout, Reckoning and Renewal. If you found value in this content, please join me in seeking solutions by becoming a $1/month patron of my work via patreon.com.