By Brian McGlinchey via Stark Realities

A principal goal of Stark Realities is to “expose fundamental myths across the political spectrum” — and few myths are as universally embraced as the notion that US participation in World War II lifted the American economy out of the Great Depression.

This myth is dangerous not only because it leads citizens and politicians to see a bright side of war that doesn’t really exist, but also because it helps foster a belief that government spending is essential to countering economic downturns. That belief, in turn, has helped propel us to a point where the national debt now exceeds $34.6 trillion, with interest payments alone on pace to reach $1 trillion a year in 2026, inviting financial catastrophe.

In part, the wartime-prosperity myth springs from the fact that, during conflict on the scale of World War II, broad, macroeconomic measures like gross national product (GNP) and the unemployment rate are completely untethered from the economy’s most important facet: the standard of living enjoyed — or endured— by everyday people.

Between 1940 and 1944, real GNP rose at an unprecedented 13% annual clip. Using GNP alone, one would think the war delivered a major improvement in the standard of living, with Americans enjoying a greater abundance of goods, accompanied by a rise in quality, selection and affordability.

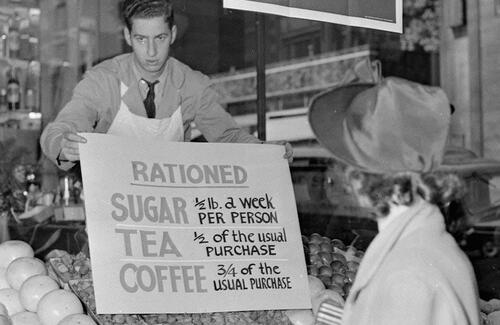

The reality was the exact opposite: Americans endured rationing, shortages, declining product quality, and the outright unavailability of many new goods, such as cars, trucks and stoves. This was the inevitable result of factories and raw materials being redirected from the creation of things consumers want to building things like tanks and fighter planes that do nothing whatsoever to improve people’s lives (setting aside the separate issue of the war’s justness).

In many respects, America experienced an outright economic devolution. In the preceding century, industrialization and the division of labor led to enormous increases in productivity. During World War II, however, shortages motivated people who’d contentedly relied on farmers to start growing their own food and canning it. The scarcity of new clothing led homemakers to redirect time and energy to sewing their own garments and resewing them to stretch as much use out them as possible.

“Those remaining on the home front were forced to produce for themselves what they had previously been able to purchase,” wrote Steven Horwitz and Michael J. McPhillips. “The household again became a center of production rather than consumption alone.”

GNP wasn’t the only measure falsely signaling wartime prosperity; employment numbers from the era were likewise misleading. The US unemployment rate plummeted from 17% in 1939 to 1.2% in 1944. Note, however, that military service members are not considered part of the labor force — which means that the draft extracted 11.5 million men from the denominator in the unemployment rate calculation.

Another 6.3 million volunteered, though many signed up because they preferred to secure a role they favored rather than face the chance of being drafted as an infantryman.

While it’s true that draftees and volunteers were “employed” by the armed forces, all these millions of men — no matter how noble their overseas missions may have been — weren’t doing anything to create prosperity at home.

That’s not to say the war machine didn’t demand laborers. With so many able men taken out of the economy, the slack was taken up by teenagers, women and retirees, many who’d have preferred to be doing other things.

In a growing economy, more people are producing goods and services, and elevating standards of living in the process. That was far from the case during World War II. Factories were humming, but they were making bayonets, bombs and battleships. “Four-tenths of the total labor force was not being used to produce consumer goods or capital capable of yielding consumer goods in the future,” noted Robert Higgs.

Defying conventional wisdom about “wartime prosperity,” Americans’ standard of living suffered tremendously from their government’s entry into World War II. In The Reality of the Wartime Economy, Horwitz and McPhillips tapped some interesting source material to bring the grim economic realities of American life during World War II into sharp focus.

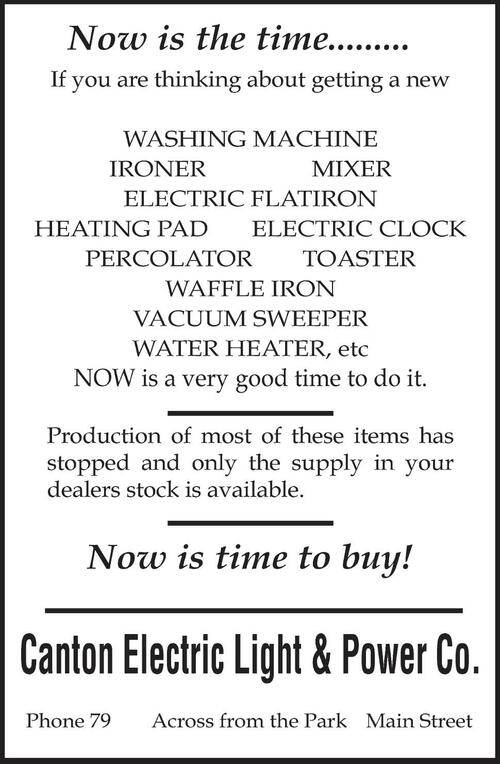

For example, a series of newspaper ads placed by Canton Electric Light & Power Company — a local New York State utility — present a vivid, time-lapse portrayal of rapidly declining conditions following the December 1941 declaration of war:

-

Foreshadowing anticipated shortages, a March 17, 1942 ad for appliances is headlined “You Can Still Buy Them.” The ad includes a qualifier that’s upbeat while still signaling creeping scarcity: “We have a fairly good supply.”

-

Just two months later, Canton Electric’s ad says “Now Is The Time” to buy various appliances and equipment, warning that “production of most of these items has stopped and only the supply in your dealers’ stock is available.”

-

Another two months later, a July 1942 ad indicates that some items that were briefly not available are back in inventory.

-

In November of that first year of America’s World War II participation, Canton Electric switched to warning consumers that, “due to the war emergency, it is quite impossible to get replacement motors for civilian use,” and urging them to ensure they’re properly maintaining their “stokers and oil burners.”

-

Later that same month, Canton Electric punted on advancing its retail business altogether, instead using its ad space to encourage readers to grow their own food, eat everything on their plates and comply with ration-stamp rules.

Horwitz and McPhillips also drew on letters written between 1942 and 1945 by Saidee Leach to her son serving in the Pacific. Contrary to the image of prosperity supposedly indicated by leaping GNP or plummeting unemployment, she tells him of:

-

Conserving scarce home-heating fuel during the coldest days by wearing fur coats indoors and residing only in their kitchen

-

Having her typewriter seized by the government, and now using a lesser model she acquired from a Howard Johnson “which had to close due to the ban on pleasure driving.”

-

Making an Easter dinner centered on fried Spam, because she “could not get fresh meat of any kind,” and later noting that “potatoes have entirely disappeared”

-

Local farmers refusing to sell their turkey flocks for Thanksgiving meals at the prices set by the Office of Price Administration — illustrating the folly of government price controls.

That is not the picture of an economy delivered from the Great Depression. Rather, “World War II institutionalized the falling standards of living of the depression through wage and price controls, and extensive rationing of consumer goods and services,” wrote Peter Ferrara. “The economic deprivation, and reduced standards of living, continued, although people perceived it was now for a good cause.”

America’s postwar experience presents another pointed contradiction of the myth of wartime prosperity.

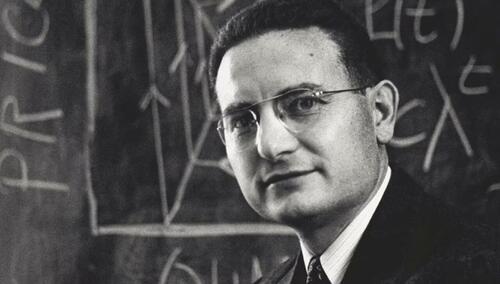

As the war’s end grew closer, Keynesian economists unanimously predicted peace would bring economic disaster. For example, Paul Samuelson said America would experience “the greatest period of unemployment and dislocation any economy has ever faced.”

Alvin Hansen warned that the economy must be kept on a centrally-controlled wartime footing, even in peacetime: "When the war is over, the government cannot just disband the Army, close down munitions factories, stop building ships, and remove all economic control.”

However, that’s pretty much what happened — and Hansen, Samuelson and their fellow economic flat-Earthers couldn’t have been more wrong about the consequences. “The year 1946, when civilian output increased by about 30 percent, was the most glorious single year in the entire history of the U.S. economy,” wrote Higgs.

This despite the fact that government purchases of goods and services collapsed by 68% between the second quarter of 1945 and the first quarter of 1946 — and upwards of a million civilian government employees were laid off and millions of service members discharged.

As war-fighting men poured back into civilian life, millions of women withdrew from the labor force, contentedly returning to duty as mothers and home managers. Rather than soaring as predicted by the “experts,” unemployment merely edged higher, from 1.9% in 1945 to 3.9% in 1947.

“Less than a year and a half after VJ-day,” crowed President Truman, “more than 10 million demobilized veterans and other millions of wartime workers have found employment in the swiftest and most gigantic change-over that any nation has ever made from war to peace.” (Note this happened despite — and in part because of — Truman’s failure to institute a higher minimum wage as the war ended.)

Having been proven enormously wrong about the economic implications of peace, Keynesians scrambled to credit the war with enabling the postwar boom, arguing that it was fueled by people drawing down savings accumulated while the supply of consumer goods was sharply restricted. However, as Higgs determined by studying the data of the time, “Holdings of liquid assets did not decline at all after the war. People financed their spending for consumer goods by reducing their saving rate.”

Contrary to the myth, it was only after World War II that — free from the government’s commandeering of factories, workers and resources, and saddled with fewer price controls and other federal market intrusions — America was finally able to emerge from the Great Depression.

You wouldn’t know that if you evaluated the economy’s health using Keynesians’ preferred measure. Just as the GNP gauge provided a 180-degree misreading of wartime economic realities, it failed in similarly spectacular fashion during the postwar boom: From 1945 to 1947, GNP plummeted 22%.

In addition to further illuminating the shortfalls of aggregate economic measures, America’s postwar economic experience delivered another broadside to the myth of World War II-fostered prosperity, and to the idea that government spending, central planning and market interventions are essential to economic achieving economic recovery.

Stark Realities undermines official narratives, demolishes conventional wisdom and exposes fundamental myths across the political spectrum. Read more and subscribe at starkrealities.substack.com

* * *

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ZeroHedge.

By Brian McGlinchey via Stark Realities

A principal goal of Stark Realities is to “expose fundamental myths across the political spectrum” — and few myths are as universally embraced as the notion that US participation in World War II lifted the American economy out of the Great Depression.

This myth is dangerous not only because it leads citizens and politicians to see a bright side of war that doesn’t really exist, but also because it helps foster a belief that government spending is essential to countering economic downturns. That belief, in turn, has helped propel us to a point where the national debt now exceeds $34.6 trillion, with interest payments alone on pace to reach $1 trillion a year in 2026, inviting financial catastrophe.

In part, the wartime-prosperity myth springs from the fact that, during conflict on the scale of World War II, broad, macroeconomic measures like gross national product (GNP) and the unemployment rate are completely untethered from the economy’s most important facet: the standard of living enjoyed — or endured— by everyday people.

Between 1940 and 1944, real GNP rose at an unprecedented 13% annual clip. Using GNP alone, one would think the war delivered a major improvement in the standard of living, with Americans enjoying a greater abundance of goods, accompanied by a rise in quality, selection and affordability.

The reality was the exact opposite: Americans endured rationing, shortages, declining product quality, and the outright unavailability of many new goods, such as cars, trucks and stoves. This was the inevitable result of factories and raw materials being redirected from the creation of things consumers want to building things like tanks and fighter planes that do nothing whatsoever to improve people’s lives (setting aside the separate issue of the war’s justness).

In many respects, America experienced an outright economic devolution. In the preceding century, industrialization and the division of labor led to enormous increases in productivity. During World War II, however, shortages motivated people who’d contentedly relied on farmers to start growing their own food and canning it. The scarcity of new clothing led homemakers to redirect time and energy to sewing their own garments and resewing them to stretch as much use out them as possible.

“Those remaining on the home front were forced to produce for themselves what they had previously been able to purchase,” wrote Steven Horwitz and Michael J. McPhillips. “The household again became a center of production rather than consumption alone.”

GNP wasn’t the only measure falsely signaling wartime prosperity; employment numbers from the era were likewise misleading. The US unemployment rate plummeted from 17% in 1939 to 1.2% in 1944. Note, however, that military service members are not considered part of the labor force — which means that the draft extracted 11.5 million men from the denominator in the unemployment rate calculation.

Another 6.3 million volunteered, though many signed up because they preferred to secure a role they favored rather than face the chance of being drafted as an infantryman.

While it’s true that draftees and volunteers were “employed” by the armed forces, all these millions of men — no matter how noble their overseas missions may have been — weren’t doing anything to create prosperity at home.

That’s not to say the war machine didn’t demand laborers. With so many able men taken out of the economy, the slack was taken up by teenagers, women and retirees, many who’d have preferred to be doing other things.

In a growing economy, more people are producing goods and services, and elevating standards of living in the process. That was far from the case during World War II. Factories were humming, but they were making bayonets, bombs and battleships. “Four-tenths of the total labor force was not being used to produce consumer goods or capital capable of yielding consumer goods in the future,” noted Robert Higgs.

Defying conventional wisdom about “wartime prosperity,” Americans’ standard of living suffered tremendously from their government’s entry into World War II. In The Reality of the Wartime Economy, Horwitz and McPhillips tapped some interesting source material to bring the grim economic realities of American life during World War II into sharp focus.

For example, a series of newspaper ads placed by Canton Electric Light & Power Company — a local New York State utility — present a vivid, time-lapse portrayal of rapidly declining conditions following the December 1941 declaration of war:

-

Foreshadowing anticipated shortages, a March 17, 1942 ad for appliances is headlined “You Can Still Buy Them.” The ad includes a qualifier that’s upbeat while still signaling creeping scarcity: “We have a fairly good supply.”

-

Just two months later, Canton Electric’s ad says “Now Is The Time” to buy various appliances and equipment, warning that “production of most of these items has stopped and only the supply in your dealers’ stock is available.”

-

Another two months later, a July 1942 ad indicates that some items that were briefly not available are back in inventory.

-

In November of that first year of America’s World War II participation, Canton Electric switched to warning consumers that, “due to the war emergency, it is quite impossible to get replacement motors for civilian use,” and urging them to ensure they’re properly maintaining their “stokers and oil burners.”

-

Later that same month, Canton Electric punted on advancing its retail business altogether, instead using its ad space to encourage readers to grow their own food, eat everything on their plates and comply with ration-stamp rules.

Horwitz and McPhillips also drew on letters written between 1942 and 1945 by Saidee Leach to her son serving in the Pacific. Contrary to the image of prosperity supposedly indicated by leaping GNP or plummeting unemployment, she tells him of:

-

Conserving scarce home-heating fuel during the coldest days by wearing fur coats indoors and residing only in their kitchen

-

Having her typewriter seized by the government, and now using a lesser model she acquired from a Howard Johnson “which had to close due to the ban on pleasure driving.”

-

Making an Easter dinner centered on fried Spam, because she “could not get fresh meat of any kind,” and later noting that “potatoes have entirely disappeared”

-

Local farmers refusing to sell their turkey flocks for Thanksgiving meals at the prices set by the Office of Price Administration — illustrating the folly of government price controls.

That is not the picture of an economy delivered from the Great Depression. Rather, “World War II institutionalized the falling standards of living of the depression through wage and price controls, and extensive rationing of consumer goods and services,” wrote Peter Ferrara. “The economic deprivation, and reduced standards of living, continued, although people perceived it was now for a good cause.”

America’s postwar experience presents another pointed contradiction of the myth of wartime prosperity.

As the war’s end grew closer, Keynesian economists unanimously predicted peace would bring economic disaster. For example, Paul Samuelson said America would experience “the greatest period of unemployment and dislocation any economy has ever faced.”

Alvin Hansen warned that the economy must be kept on a centrally-controlled wartime footing, even in peacetime: “When the war is over, the government cannot just disband the Army, close down munitions factories, stop building ships, and remove all economic control.”

However, that’s pretty much what happened — and Hansen, Samuelson and their fellow economic flat-Earthers couldn’t have been more wrong about the consequences. “The year 1946, when civilian output increased by about 30 percent, was the most glorious single year in the entire history of the U.S. economy,” wrote Higgs.

This despite the fact that government purchases of goods and services collapsed by 68% between the second quarter of 1945 and the first quarter of 1946 — and upwards of a million civilian government employees were laid off and millions of service members discharged.

As war-fighting men poured back into civilian life, millions of women withdrew from the labor force, contentedly returning to duty as mothers and home managers. Rather than soaring as predicted by the “experts,” unemployment merely edged higher, from 1.9% in 1945 to 3.9% in 1947.

“Less than a year and a half after VJ-day,” crowed President Truman, “more than 10 million demobilized veterans and other millions of wartime workers have found employment in the swiftest and most gigantic change-over that any nation has ever made from war to peace.” (Note this happened despite — and in part because of — Truman’s failure to institute a higher minimum wage as the war ended.)

Having been proven enormously wrong about the economic implications of peace, Keynesians scrambled to credit the war with enabling the postwar boom, arguing that it was fueled by people drawing down savings accumulated while the supply of consumer goods was sharply restricted. However, as Higgs determined by studying the data of the time, “Holdings of liquid assets did not decline at all after the war. People financed their spending for consumer goods by reducing their saving rate.”

Contrary to the myth, it was only after World War II that — free from the government’s commandeering of factories, workers and resources, and saddled with fewer price controls and other federal market intrusions — America was finally able to emerge from the Great Depression.

You wouldn’t know that if you evaluated the economy’s health using Keynesians’ preferred measure. Just as the GNP gauge provided a 180-degree misreading of wartime economic realities, it failed in similarly spectacular fashion during the postwar boom: From 1945 to 1947, GNP plummeted 22%.

In addition to further illuminating the shortfalls of aggregate economic measures, America’s postwar economic experience delivered another broadside to the myth of World War II-fostered prosperity, and to the idea that government spending, central planning and market interventions are essential to economic achieving economic recovery.

Stark Realities undermines official narratives, demolishes conventional wisdom and exposes fundamental myths across the political spectrum. Read more and subscribe at starkrealities.substack.com

* * *

Views expressed in this article are opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of ZeroHedge.

Loading…