Authored by Law Ka-chung via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

The latest China data continue to show an overall downtrend, although some rebound is seen. The domestic economy, as represented by internal demand (private and government consumption expenditure and investment), remains weak under deleveraging (paying off debts). One possible way to improve the situation is to rely on external demand, which is net exports. At first glance, this seems sensible because the outside world is in a much better shape economically than China. However, the global cyclical pulldown effect can offset this completely.

The standard way to counter such a headwind is to “lower the price;” it can be done actively by policymakers or automatically under market mechanisms. A worsening outlook ahead will lead to a fall in prices, be they prices of goods, assets, or others. This is a market outcome that is the most natural yet the most uncontrollable. In order to take a more active approach, policymakers often cut interest rates or depreciate exchange rates to restore competitiveness. Here the interest rate affects the price of an investment, while the exchange rate affects the price of net exports.

Given both interest and exchange rates are sector-specific, the impact of changing either is different. Lowering interest rates benefits the borrowers while sacrificing the savers (or lenders). This affects who holds or loans money over time. However, depreciating the exchange rate impacts not over time but across borders: those within the border will gain an advantage in exporting yet will be disadvantaged in importing. While those outside the border will gain by paying less for goods.

As China is undergoing prolonged housing and debt crises, the interest rate tool would be ineffective because deleveraging to eliminate the debts usually takes longer than the effective duration of the interest rate cut. Similar classic examples are in post-1990 Japan and the post-2007 U.S., where even a zero interest rate with quantitative easing did not help.

However, exchange rate depreciation may make more sense (given the sharp contrast in economic performance between China and the rest of the world), as competitiveness in exports would be improved.

This is a traditional argument, but hold on. Now the global supply chain in production is so lengthy that countries might contribute only a portion of the total goods value at a lower exchange rate. Also, for a country importing $100 of raw materials or semi-finished goods and adding value then exporting it at $110, the exchange rate change affects the $10 value-added part only rather than the total exports of $110—China falls into this category. This is why exchange rate depreciation might not be as effective as one might think in helping China’s export figures.

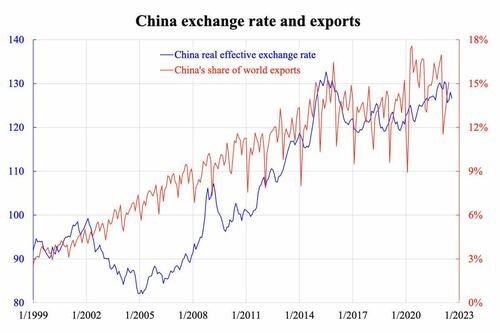

As the accompanying chart shows, China’s share of world exports moves in unison with its real effective exchange rate. This means a cheaper Yuan does not boost exports. Instead, the opposite is seen—when the exports boom, it drives capital inflow, and the exchange rate appreciates. Depreciation is not a way out, either.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.

Authored by Law Ka-chung via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

The latest China data continue to show an overall downtrend, although some rebound is seen. The domestic economy, as represented by internal demand (private and government consumption expenditure and investment), remains weak under deleveraging (paying off debts). One possible way to improve the situation is to rely on external demand, which is net exports. At first glance, this seems sensible because the outside world is in a much better shape economically than China. However, the global cyclical pulldown effect can offset this completely.

The standard way to counter such a headwind is to “lower the price;” it can be done actively by policymakers or automatically under market mechanisms. A worsening outlook ahead will lead to a fall in prices, be they prices of goods, assets, or others. This is a market outcome that is the most natural yet the most uncontrollable. In order to take a more active approach, policymakers often cut interest rates or depreciate exchange rates to restore competitiveness. Here the interest rate affects the price of an investment, while the exchange rate affects the price of net exports.

Given both interest and exchange rates are sector-specific, the impact of changing either is different. Lowering interest rates benefits the borrowers while sacrificing the savers (or lenders). This affects who holds or loans money over time. However, depreciating the exchange rate impacts not over time but across borders: those within the border will gain an advantage in exporting yet will be disadvantaged in importing. While those outside the border will gain by paying less for goods.

As China is undergoing prolonged housing and debt crises, the interest rate tool would be ineffective because deleveraging to eliminate the debts usually takes longer than the effective duration of the interest rate cut. Similar classic examples are in post-1990 Japan and the post-2007 U.S., where even a zero interest rate with quantitative easing did not help.

However, exchange rate depreciation may make more sense (given the sharp contrast in economic performance between China and the rest of the world), as competitiveness in exports would be improved.

This is a traditional argument, but hold on. Now the global supply chain in production is so lengthy that countries might contribute only a portion of the total goods value at a lower exchange rate. Also, for a country importing $100 of raw materials or semi-finished goods and adding value then exporting it at $110, the exchange rate change affects the $10 value-added part only rather than the total exports of $110—China falls into this category. This is why exchange rate depreciation might not be as effective as one might think in helping China’s export figures.

As the accompanying chart shows, China’s share of world exports moves in unison with its real effective exchange rate. This means a cheaper Yuan does not boost exports. Instead, the opposite is seen—when the exports boom, it drives capital inflow, and the exchange rate appreciates. Depreciation is not a way out, either.

Views expressed in this article are the opinions of the author and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Epoch Times or ZeroHedge.