American presidential campaigns have become increasingly vitriolic. One of President Biden’s campaign organizations even explicitly compared Trump to Hitler, Terms like “fascist” and “mentally unbalanced” are commonplace. The venerable Atlantic magazine recently ran a story titled, “Trump Is Speaking Like Hitler, Stalin, and Mussolini.” A Harvard Business Review essay warned: “The campaign vitriol has already begun, and many leaders are dreading what this is going to bring into their workplaces and onto their teams.” Worries abound that this conflict may become violent if one side feels that the other has won unfairly.

What explains this vitriol? Are we becoming a less civil nation? Are the election stakes so high that the prospect of losing invites violence? A more plausible explanation is that the Internet, in undermining face-to-face relationships and thus promoting social disengagement, allows extreme sentiments to go unchecked. In an earlier time, somebody who insisted that the Republican presidential nominee was a secret Russian agent would find scant support among friends and family, and absent social reinforcement, the wild opinion would likely dissipate.

Today, by contrast, nothing impedes the unhinged, and these unfiltered opinions quickly enter the marketplace of ideas. Yesterday’s activist would take his soapbox to the public square and speak to a mere handful; today this “soapbox” has a keyboard and sits on his desk and provides direct access to millions of potential listeners. Those who believe that the Holocaust never happened can find multiple websites confirming this belief.

Historical studies of public opinion show this transformation. In 5th-century B.C. Athens, the “marketplace of ideas” was literally a marketplace — the Agora — where citizens traded gossip and opinions. Like olive oil, ideas were “sold,” and nonsense was rejected. Crackpots would not get very far, and if he persisted, the penalty was being ostracized. Public discussions could thus yield some good ideas while discarding the noise. The New England town hall also embodies this ancient give-and-take of ideas.

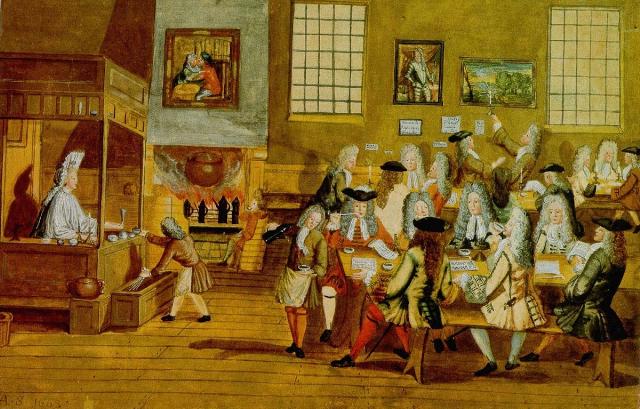

In early 18th-century London, some 2000 coffeehouses provide settings where people could discuss almost everything while Parisian salons served a similar purpose. Germany had their Tishgeschellschaften (table societies).

These forums moderated wackiness. Those expressing half-baked conspiracies would quickly invite ridicule, and nobody wanted to be embarrassed. Or perhaps others would add their own two cents, strengthening the argument, offering evidence and logical structure, so what began as a dubious idea might be refashioned into something useful.

<img alt captext="Public Domain” class=”post-image-right” src=”https://conservativenewsbriefing.com/wp-content/uploads/2024/10/the-rise-of-political-vitriol.jpg” width=”450″>Worthy ideas expressed in one coffeehouse might be spread more widely thanks to journalist reporting, most famously The Tatler edited by Richard Steel, Samuel Johnson’s The Rambler, or Oliver Goldsmith’s Citizen of the World. These publications served as the Internet of the day, but opinions were scrutinized before being written down, so nonsense was filtered out.

By contrast, today’s communications via the Internet liberate people from social constraints. No friends or family can intervene, and while London of the 18th century offered 2000 coffeehouses to serve as a soapbox, today’s Internet provides thousands of sites catering to anything imaginable, In fact, 12 million people believe that the U.S. is secretly run by lizards. Entering the “public debate” is easy. Just create one’s own blog, write for an existing webzine, become a commentator or join a Facebook group of fellow cranks, all the while enjoying the comforts of one’s home. While guidelines exist, they are relatively minor and largely concern matters of language.

The social pressures that encouraged moderation no longer exist. Deranged fans of dark plots would undoubtedly have been asked to leave Paris salons, but the Internet lacks such gatekeepers. Incentives may exist in the opposite direction since radical views will stand out among thousands of duller rival forums. A thoughtful plain vanilla analysis of Donald Trump’s personality is far less riveting than “proof” of his methamphetamine addiction. Looney ideas have the advantage of breaking through the clutter.

The Internet also lacks the normal rules of decorum. No London coffeehouse customer would be allowed to hurl insults and scream at fellow patrons since this would ruin business. This imposed civility is no longer true. This anonymous hyper-vitriol of often called “flaming” or “a flame war,” and given that most people are adverse to such rancor, “flaming” can push discussions to even greater extremes. Few reasonable people will participate if regularly insulted, and so the forum is soon dominated by true believers. This is far different from normal social groups where harmony is the norm,

This trend is compounded by the rise of business models built around targeting narrow populations. This is a shift from broadcasting to narrowcasting. For example, prior to the 1990s and the rise of cable TV, major networks attracted a politically diverse viewership, and thus hewed to the middle, even avoiding politics altogether. Extremism drove many away, so catering to a narrow ideological fraction was financial suicide.

But the rise of cable TV encouraged targeting thinner and thinner population slices, so while MSNBC tilted left, Fox Cable News shifted rightward, and programming increasingly became politically one-sided. Now those with distinct points on the political spectrums follow news and entertainment reinforcing their narrow political views. A comparable pattern occurred in websites, podcasts, and other media outlets so that what might have once been labeled “extreme” now appears perfectly normal.

Similarly, major newspapers like the NY Times once targeted large metropolitan areas with an ideologically mixed readership. News reporting thus avoided ideological extremes to avoid losing readers. Today, thanks to on-line subscriptions, the Times has a national readership, and while those on the far Left may only be 10% of the population, their total national size is sufficient to make money. In the case of the Times, tilting coverage leftward thus becomes a viable business model. All and all, the Internet makes it profitable to seek out once ignored markets. A black feminist in rural Iowa once had few options. Today, thanks to the Internet, she can daily pursue this interest. Multiply this targeting by a thousand, and it is no wonder that Americans increasingly live in bubbles that reenforces their existing views so once extreme views have become “normal.”

These factors are unlikely to be reversed. People living in an environment saturated with radical Marxist ideology are not about to seek out ideological diversity by creating a discussion group welcoming all viewpoints. Why attend a meeting and risk being criticized for your allegedly utopian views and told that your anti-Trump acrimony is out of order? Ditto for those on the Right — who wants to hear that obsessing over urban crime is just dog whistle white racism?

Political life may become even more vitriolic as older American who remember an earlier era of moderation are replaced by those who know only ideological homogeneity. Indeed, many youngsters have become so addicted to their electronic devices that they struggle with the most basic social interactions. At some point the current acrimonious Trump/Harris battle may be recalled as a relatively peaceful contest where the harshest insults was just “he’s worse than Hitler” or “she’s a communist.” The good old days.

Image: Public Domain