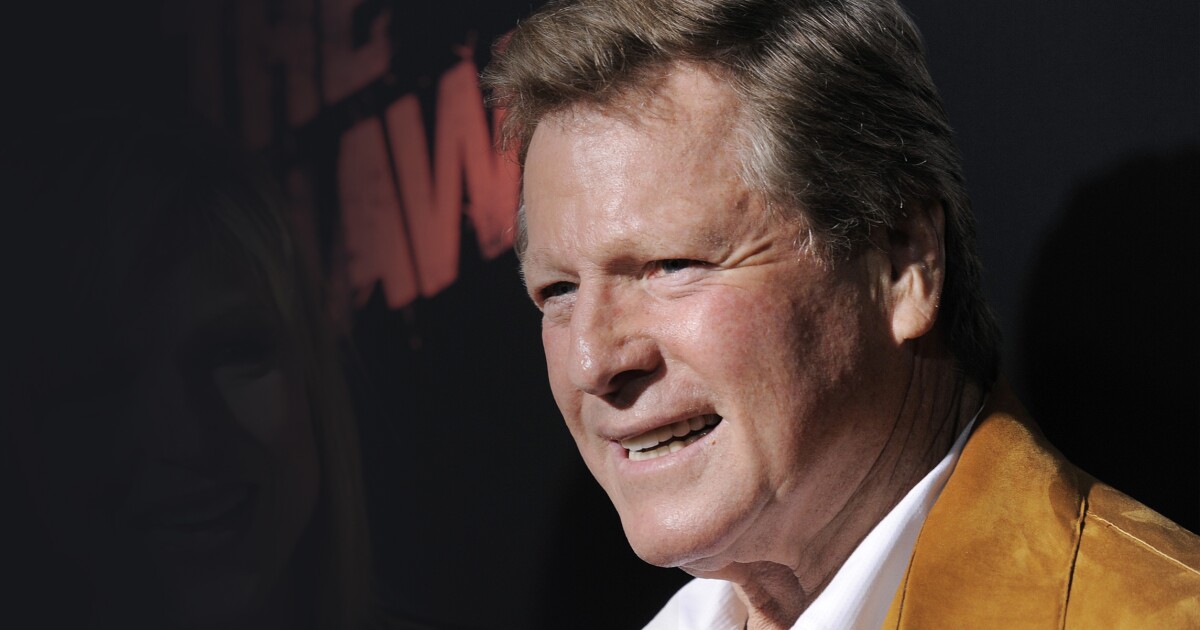

Although his career began as the studio system was winding down, and his personal life was plagued by the excesses of the modern age, Ryan O’Neal sometimes seemed like the last actor of the Golden Age.

When Hollywood wanted a leading man with charm and command, they called on O’Neal. He was the tragic romantic in Love Story, the Cary Grant-like farceur in What’s Up, Doc?, and the only actor of his generation to successfully anchor a sprawling, old-fashioned period epic with Barry Lyndon.

Like the stars of old, O’Neal, who died on Dec. 8 at the age of 82, was neither a tough guy nor a pretty face but some combination of both. In several of his best parts, his classically handsome looks masked volcanic emotions, expressed in fragments of fury or violence. In many ways, he never completely left behind his background as an amateur boxer: sturdy in bearing, sure on his feet, and occasionally explosive.

O’Neal also suffered from the limitations of being a relic. Nearly all of his contemporaries found ways to stay relevant, but he preferred to stay at home in Malibu. O’Neal was a product of his time who was stuck in his time. Unlike Al Pacino, he generally shunned, or was not offered, parts that called for revealing inner depths. Unlike Robert Redford, he did not prolong his career by switching to directing. And unlike Robert De Niro, he was not desperate to work all the time — at least not in movies or as leads.

Further distinguishing him from his peers, O’Neal did not get his start on the stage but in the shadow of the studios. Born in Los Angeles in 1941, O’Neal was the son of screenwriter Charles O’Neal, whose relatively unremarkable screen credits — among them Cry of the Werewolf (1944), Vice Squad (1953), and The Alligator People (1959) — are nonetheless spread over multiple decades. In his father, then, Ryan had the example of someone who made a living in show business, and once he broke into the industry, he displayed a similar industriousness. Guest spots on The Virginian, The Untouchables, My Three Sons, and countless other shows led to a central role on the prime-time soap opera Peyton Place, the latest and arguably most popular incarnation of a franchise that had begun with a 1956 novel and continued with a 1957 feature film.

The series ran from 1964 to 1969, and by the time it ended, the studios were no longer looking for leading men but hippies, weirdos, and dropouts — approximately the situation sketched in Quentin Tarantino’s Once Upon a Time in Hollywood. Yet there was one exception: Paramount boss Robert Evans, who, sensing pent-up audience demand for an unapologetically full-throated romance, greenlighted Love Story, starring O’Neal and Ali MacGraw.

The 1970 blockbuster’s grating treacle — “Love means never having to say you’re sorry” and all the rest — should not overwhelm its genuine value as silent majority-style blowback against the counterculture. Few stars could be as opposed to the likes of Dennis Hopper, Peter Fonda, or even Jack Nicholson than the clean-cut, preppily dressed O’Neal in Love Story.

A number of leading directors seized on O’Neal’s old-fashioned virtues. Blake Edwards cast him alongside William Holden in the mournful Western Wild Rovers (1971), while Peter Bogdanovich, a partisan of the Golden Age, gave him two of his best parts in What’s Up, Doc? (1972) and as a grinning, conniving Depression-era swindler in Paper Moon (1973), the latter co-starring his own daughter, Tatum, who won an Oscar. Stanley Kubrick recognized that O’Neal was perfect to play a callow Irishman who finds history and tragedy thrust upon him in Barry Lyndon (1975), the one uncontestable pantheon-level masterpiece of the actor’s career.

By then, though, troubles were brewing. Talented director Walter Hill tapped the icy reserves underneath O’Neal’s cool countenance in the neo-noir The Driver (1978), but other good parts were increasingly hard to come by. While Redford and De Niro were winning Oscars, O’Neal had to content himself with the likes of So Fine (1981) and Irreconcilable Differences (1984). He found a sparring partner worthy of him in Norman Mailer, who, in one of his occasional directorial efforts, cast O’Neal in the highly eccentric drama-thriller Tough Guys Don’t Dance (1987), a simultaneous embrace and overwrought parody of its leading man’s stolidity.

Closer to home, O’Neal reckoned with — and openly admitted — his limitations as a parent to the four children he fathered with his two wives, Joanna Moore and Leigh Taylor-Young, and his longtime companion, Farrah Fawcett. Tatum O’Neal, for all her gifts, contended with substance abuse; her brother, Griffin, and her half-brother, Redmond, have had multiple collisions with the law. Here, O’Neal faced the depressingly ordinary reality of a scandal-plagued Hollywood home life.

In the end, O’Neal embodied both the tragedy and the promise of a life led on the silver screen — but, in such estimable films as What’s Up, Doc?, Paper Moon, and Barry Lyndon, it’s the latter that will endure in our memories.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Peter Tonguette is a contributing writer to the Washington Examiner magazine.