–>

July 5, 2022

It has been fifty years since that momentous break-in at the Watergate office complex, and it seems a good time to revisit that episode, especially in light of the current abuses of power that seem so ubiquitous. Geoff Shepard’s book, The Real Watergate Scandal and the just published book by Garrett Graff, Watergate, a New History, offer different perspectives. Shepard is more interested in the legal process and its abuse, while Graff’s book relies more on the infamous White House tapes. It is the more comprehensive of the two. Here are some of observations based on these histories.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

Nixon probably didn’t know about the burglary of Watergate beforehand, but he created the atmosphere where it could be expected, and where his underlings could believe this tactic was acceptable. Nixon participated in the planning of the burglary of the Brookings Institution, although this break-in was cancelled. In a conversation with Nixon, John Ehrlichman referred to the break-in of the office of Daniel Ellsberg’s psychiatrist as “one little operation…out in Los Angeles.” If that break-in was just a “little operation,” why not burglarize the headquarters of the Democrats?

Nixon certainly knew about and participated in the cover-up after the burglars were caught. Given all that he and his underlings had done, coupled with the unrelenting hostility of the Democrats, the press, and those in the office of the special prosecutor, Nixon’s resignation was inevitable.

Both books portray John Dean as a self-serving weasel, who testified only after saving his own skin. In his role as legal counsel to the President, he coordinated efforts to obstruct the FBI and grand jury investigations, concealed and destroyed evidence, helped prep witnesses for their perjured testimony. As events became more dire, it was Dean who was the first to seek immunity for his testimony against his colleagues. Despite his many crimes, Dean skated, and he never served a day of prison time. John Dean was “Guilty as hell, free as a bird,” as domestic terrorist Bill Ayers once put it.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Dean’s account of his experiences in Watergate were set out in his book, Blind Ambition. However, in a later civil case he disavowed much of his own book and claimed that much of it was the invention of a ghost writer. Why Graff cites this book as authority in his footnotes is beyond me. Yet Dean sold the book as its author and no doubt kept his share of the sale proceeds, which is consistent with Dean’s character as portrayed in these books. Dean has since appeared occasionally as a commentator on MSNBC or CNN, which are the lower circles of hell where he richly deserves to be.

Mark Felt (Deep Throat) was a bitter, vindictive man who resented not being appointed Hoover’s successor at the FBI. He made Nixon pay for this decision.

G. Gordon Liddy and Howard Hunt were the leaders of the burglary team. Liddy was smart but certifiably crazy. His and Hunt’s ineptitude in planning and carrying out the burglary are worthy of the Keystone Cops, and it shows how simple ineptitude can metastasize into something devastating.

The handling of the criminal cases against “all the president’s men” was disgraceful as Shepard makes clear. What the president’s men did was criminal, but that shouldn’t have been a pretext for denying them fair trials and due process.

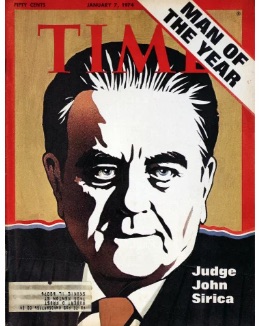

Judge John Sirica (Time’s “Man of the Year,” 1973) was an often-reversed, publicity-seeking, political hack. He manipulated the District Court’s procedure so that he could have assigned to himself the juicy Watergate cases. He saw his role not as an impartial judge, but as an investigator and prosecutor. That is just how he conducted his proceedings.

Judge John Sirica (Time’s “Man of the Year,” 1973) was an often-reversed, publicity-seeking, political hack. He manipulated the District Court’s procedure so that he could have assigned to himself the juicy Watergate cases. He saw his role not as an impartial judge, but as an investigator and prosecutor. That is just how he conducted his proceedings.

He refused to allow a change of venue despite the media feeding frenzy in Washington. Why change the venue when you can be favorably portrayed in the Washington Post every day? He conducted cursory and even ridiculous “voir dire” of potential jurors that guaranteed biased juries. (Could there be any other kind in DC when Republicans are charged?) He made prejudicial comments in front of the jury. He sought to bolster John Dean’s credibility by giving him a long prison sentence following his guilty plea. He did so knowing that Dean would never serve a day, and that he would commute or cancel this sentence once Dean testified as Sirica wanted.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Most seriously, and in violation of any standards of judicial and prosecutorial behavior, Sirica had many private meetings with prosecutors (both Cox and Jaworski) with no defense counsel present. Here they discussed tactics and strategies for the trials, Sirica acting more as co-counsel than judge. Sirica even provided a list of more persons he wanted the special counsel to indict. So much for due process and trials overseen by an impartial judge.

At this time, Judge David Bazelon was chief judge of the DC Circuit Court of Appeals. The DC Circuit had nine judges, five of whom were Democrats, and all appeals from the DC District Court (including those from Judge Sirica’s court) go to the DC Circuit Court. A typical appeals panel consists of three judges picked randomly.

In a blatantly unethical meeting, Archibald Cox met with Bazelon with no defense counsel present. He was able to get Bazelon to agree that all appeals from any Watergate case coming out of the DC District Court would be heard “en banc,” or before all nine judges. By so agreeing, Bazelon guaranteed that there would never be a case where there could be a three-judge panel with a Republican majority. The Democrats would always have the majority and the prosecutors would win any appeal. Not surprisingly, no appeals of Watergate defendants were successful.

At the very least, the actions in these Watergate criminal cases by Sirica, Bazelon, and the prosecutors were unethical and prejudicial. Had these meetings come to light at that time, they would have been grounds for new trials or changes of venue outside the DC District Court. These prejudicial actions could have led to impeachment of the judges and even disbarment after an honest accounting of how these cases were prosecuted. But these meetings were never disclosed when it mattered. Graff’s book, which claims to be all-encompassing, ignores serious consideration of these due process issues.

I have never admired Richard Nixon, and I have always thought he did a lot of long-term damage to the country beyond Watergate itself: wage and price controls, the enhancement of EPA’s often arbitrary power, institutionalized racial quotas in the name of “affirmative action,” arms control agreements that the Soviets were violating before the ink was dry, “detente” that the Soviets manipulated to their advantage, his role in the creation of a rabidly partisan press corps that we live with today. Yes, he did some good: China, the denouement of the 1973 Middle East war, the end of the Vietnam War. Unfortunately, like Donald Trump, too often his demons got the best of him, as both books demonstrate.

Among many lessons, Watergate shows us how power can corrupt and how investigations and legal processes can be abused. This is just what we saw with the case of Michael Flynn, among many others, post 2016, and as we now see with the selective and politically motivated prosecutions by the Biden Justice Department; Attorney General, Merritt Garland being every bit the light weight, political hack that John Sirica was.

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>