One Christmas, a foreign detective stays with an English family in their ancient manor house in the countryside. His hosts at Kings Lacey believe he is there to experience an old-fashioned English Christmas. In reality, he has been hired by a senior state official to prevent an international scandal and recover a stolen ruby. The detective enjoys Christmas with all its traditions and trappings — a decorated tree, filled stockings, stuffed turkeys — but is initially wary of the Christmas pudding. This large ball of a dessert looks impressive, “a piece of holly stuck in it like a triumphant flag and glorious flames of blue and red rising round it.” But the previous night, he found an anonymous note in his room containing a short, stark warning: “DON’T EAT NONE OF THE PLUM PUDDING. ONE AS WISHES YOU WELL.”

This cryptic note heralds more disturbances that cast a shadow over the festivities. Someone drugs the detective’s coffee, then searches his room. On the morning of Dec. 26, some children attempt to “make him feel at home” by staging a mock murder. But the prank backfires when the person pretending to be dead in the snow turns out to have no pulse. Shortly afterward, the body disappears. “Someone,” the detective remarks, “has turned the comedy into a tragedy.”

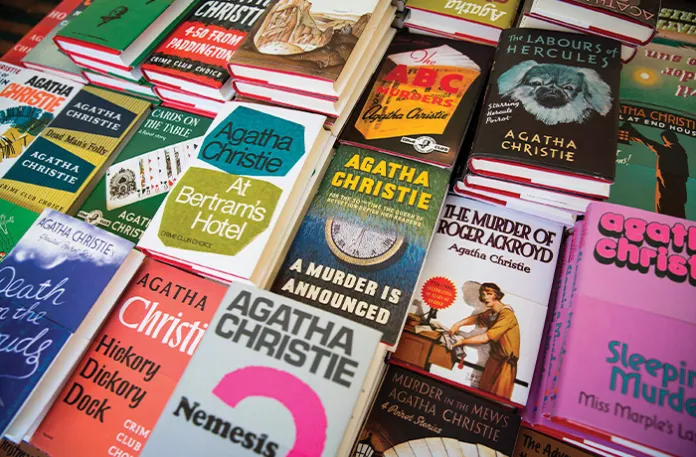

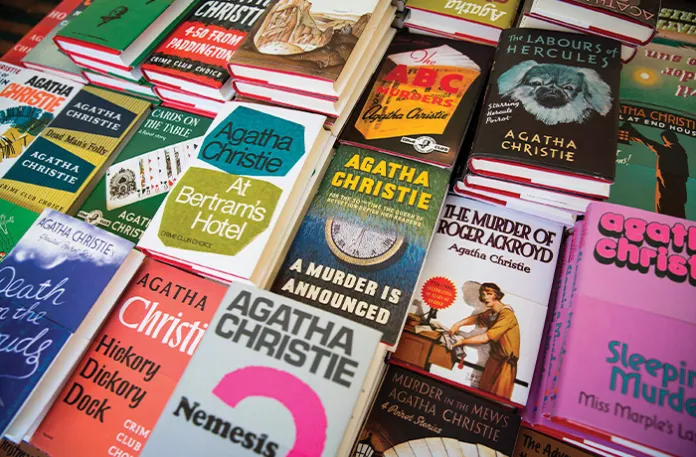

Originally published in 1923, “The Adventure of the Christmas Pudding” is a seasonal story by Agatha Christie. It features many of the Queen of Crime’s signature tropes. The foreign detective is, of course, Hercule Poirot, that fussy, dandy Belgian ex-policeman with an “egg-shaped head” and “enormous moustaches.” There is the country house setting, which is both a domestic space and a closed-off, self-contained society. Its occupants, all suspects, comprise seemingly “normal” individuals, ne’er-do-wells, a cranky old patriarch given to splenetic, and often xenophobic, outbursts (“Can’t think why you want one of these damned foreigners here cluttering up Christmas,” fumes Colonel Lacey) and even a butler who, like all good manservants, “noticed nothing that he was not asked to notice.” Christie imbues the proceedings with smoke and mirrors and sharp twists and turns. By the end of the tale, Poirot might well have cluttered up Christmas, but he has also managed to solve a fiendish whodunnit.

For many readers, Christie is synonymous with Christmas. In some respects, this makes sense, for she employed the holidays in particular and winter in general to good effect in her writing. A snowscape forms the backdrop to two of her most famous works; in Murder on the Orient Express (1934), the characters are brought together by a snowdrift, while in the 1952 play The Mousetrap, the cast are trapped by a snowstorm. Two of Christie’s winter tales deal with notable cases of failure. “The Chocolate Box” (1923) welcomes the reader in: “It was a wild night. Outside, the wind howled malevolently, and the rain beat against the windows in great gusts. Poirot and I sat facing the hearth, our legs stretched out to the cheerful blaze.” We then learn of a rare occasion when, in the words of the Belgian sleuth, “My gray cells, they functioned not at all.” Elsewhere in a chillier story, “A Christmas Tragedy” (1991), Christie’s other famous detective, Miss Marple, tells of a man who killed his wife. Marple proves Mr. Sanders’s guilt after realizing that a Christmas present in a locked cupboard is a key clue, but reproaches herself for failing to save Mrs. Sanders’s life. “But,” she asks, “who would have listened to an old woman jumping to conclusions?”

4.50 From Paddington (1957) opens in the run-up to Christmas with Mrs. McGillicuddy leaving London on what is “a dreary misty December day” — but not so misty that she can’t see a man strangling a woman in the window of a passing train. The Sittaford Mystery (1931) begins with an evocative scene of a winter wonderland “as depicted on Christmas cards and in old-fashioned melodramas,” but this charming tableau soon gives way to the grim spectacle of a dead body in a study. Serenity is similarly snuffed out by brutality in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas (1938). The tyrannical Simeon Lee gathers his family for Christmas at Gorston Hall, but after calling them all useless, cutting off allowances, and changing his will, he is found in a pool of blood with his throat slit. When a Spanish woman tells Lee’s son that she thought English holidays were happier affairs, he dryly replies, “Ah, but you must have a Christmas uncomplicated by murder.”

It would appear, then, that Christmas crops up regularly in Christie’s work. In actual fact, it doesn’t. Christie’s Christmas-themed books and stories constitute only a fraction of her vast output. She killed off characters all year round and complicated every occasion with murder. So why do we associate Christmas with her? And, by extension, why do we like to read about crime at Christmas?

For British readers, particularly in the post-war period, Christie and Christmas were interlinked because of a shrewd marketing campaign of the author’s publisher. The slogan “A Christie for Christmas” was a fixture in HarperCollins’s publishing list. Readers certainly had plenty of choice for reading material; between 1920 and 1976, Christie wrote one book a year, and for almost 20 of those years she produced two titles. What better stocking-filler than a bestselling murder mystery?

It is important to clarify what kind of murder mysteries Christie wrote. If she were writing today, her books would be bought alongside those of Richard Osman (whose Thursday Murder Club series is a nod to Christie’s 1933 short story “The Tuesday Club Murders”) and filed under “cozy crime.” It is a dubious term — since when was murder cozy? — and yet a necessary subgenre, one that sets apart clue-puzzle writing and narratives largely devoid of blood from darker, grislier police procedurals. Christie delighted in murder most foul but spared her readers gruesome details. Only in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas did she deliver what she called a “good violent murder with lots of blood” in response to her brother-in-law’s complaint that her murders were getting too “anemic.”

Cozy crime and Christmas make for a winning combination. While temperatures plummet outside, readers can fix a warm drink, curl up on the sofa under a blanket, and lose themselves in an absorbing atmospheric mystery. Christie’s mysteries are, essentially, comfort reads. They follow a recognizable format; intriguing plots and colorful characters power them; they offer pleasure through misdirection and deception; and they always culminate in a cathartic denouement in which cases are solved, killers are exposed, and order is restored.

Christie’s books are also comforting because of their nostalgic appeal. All of her novels, especially those from the 1920s and 1930s, the so-called Golden Age of detective fiction, are period pieces that present England as a green and pleasant land. People live in cities free from societal ills or in picturesque villages such as Miss Marple’s St Mary Mead or in grand country estates. Until someone ends up bullied or blackmailed, or stabbed or poisoned, relative harmony reigns throughout tight-knit communities, and old traditions (including Christmas ones) are upheld. Successive film and TV adaptations have reinforced these soft-focus images. As the Chicago Tribune put it in 1991, “the fictional world that Christie created – with its antique-filled drawing room, manicured gardens and orderly, gore-less murders that rarely left so much as a stain on the Aubusson rug – seems increasingly quaint.”

Perhaps the one nostalgic aspect that Christie’s readers are drawn to is her heroes’ methods of detection. In a world before cellphones, surveillance cameras, and DNA testing, Poirot et al. must resort to good-old-fashioned sleuthing, finding and weighing up the significance of all manner of physical clues, from a dropped monogrammed handkerchief to a stopped clock to an uneven row of oyster shells. In these books, detectives follow real fingerprints, not their digital equivalents. In addition, they set great store by what we would today term psychological profiling. “The psychology of character is interesting,” says Poirot in Lord Edgware Dies (1933). “One cannot be interested in crime without being interested in psychology. It is not the mere act of killing, it is what lies behind it that appeals to the expert.”

Christie’s work hits the spot at Christmas for various other reasons. As we prepare, willingly or otherwise, to eat, drink, and be merry with relatives, we read about Christie’s families, many of them squabbling over inheritances or old grievances, and take solace from the fact that they are more dysfunctional than our own.

The most wonderful time of the year also provides an opportunity to relish Christie’s take on wonder — miraculous deeds, strange phenomena, otherworldly characters. There is The Pale Horse (1961), with its three “witches,” Sleeping Murder (1976), which features a supposedly haunted house and a woman afflicted by déjà vu, and a stream of books and stories that include séances, deities, doubles, and psychic visions. The season to be jolly allows us to appreciate Christie’s subtle humor, which is often sourced from Poirot’s mangled English idioms. In The A.B.C. Murders (1936), he believes he “may be making the mountain out of the anthill”; in the 1947 collection The Labours of Hercules, he accuses someone of “barking up the mistaken tree”; best of all, in the story “The Under Dog: A Hercule Poirot Short Story,” he declares: “One would hardly think a young man of that type would have the – how do you say it – the bowels to commit such a crime.”

MAGAZINE: THE GERMAN RESISTANCE TO HITLER

Above all, what we get from Christie’s books during the festive period is plain and simple escapism. This is much needed, for Christmas, though fun, is also hectic. When a character in Hercule Poirot’s Christmas asserts that Christmas is an unlikely season for crime, the eponymous detective scoffs at the notion of a period of peace and goodwill. Christmas is stressful, he argues, epitomized by fraught family gatherings. Putting a brave face on things can prove disastrous. “The result of pretending to be a more amiable, a more forgiving, a more high-minded person than one really is, has sooner or later the effect of causing one to behave as a more disagreeable, a more ruthless and an altogether more unpleasant person than is actually the case!” Poirot claims, adding: “If you dam the stream of natural behavior, mon ami, sooner or later the dam bursts and a cataclysm occurs!”

Christie’s winning brand of escapist fare isn’t always cozy. One of her masterpieces, And Then There Were None (1939), which explores evil and retribution, is a compellingly brutal book, one that, in the words of historian Lucy Worsley, “marked a new level of achievement for Agatha as she becomes the supremely confident dispenser of death to those among the characters who deserve it.” But what all this death-dispenser’s books have in common is their ability to take us out of our own worlds and into hers to indulge in an elaborate guessing game. Invariably, Christie will outwit us and her detectives will outpace us, but it is still satisfying to accept the challenge, marvel at the legerdemain, and play along, while keeping in mind this pertinent line from Christie’s 1949 novel Crooked House: “What it comes to in the end is that everybody, perhaps, is capable of murder.” Even at Christmas.

Malcolm Forbes has written for the Economist, the Wall Street Journal, and the Washington Post. He lives in Edinburgh.