Everybody’s in LA, John Mulaney’s six-part Netflix live talk show, loosely about Los Angeles, is a lesson in the promise and peril of taking artistic risks. Created to coincide with the “Netflix Is a Joke” humor festival, the show teased its ad hoc premise with winking promos depicting awkward vox pops with real Angelenos, promises of talent “equal to, but not necessarily, Jerry Seinfeld, Chris Rock, and David Letterman,” and framing that warned viewers that the show will kind of, well, make things up as it goes. Fair play, and kudos for the moxie — though some viewers will enjoy this thrown-together meal even as others wish Mulaney would discard freestyle cooking and return to the comic equivalent of a Julia Child recipe.

Mulaney, one of America’s most successful stand-up comics and a generally deft showman, has indicated that the series was born from a desire to take advantage of the fact that so many comedians would be in town at the same time. Although Everybody’s in LA has its eccentric charms, the whole edifice leans on an assumption — putting funny people together in a room inevitably leads to an entertaining outcome — that is at times tested. Jerry Seinfeld’s Comedians in Cars Getting Coffee may be the best-known example of this conceit, though so many other shows, podcasts, and the like have pursued it, and with such uneven results, that by 2022 the film Bodies Bodies Bodies depicted someone sighing as another character pitches her a podcast about “hanging out with your smartest and funniest friend.”

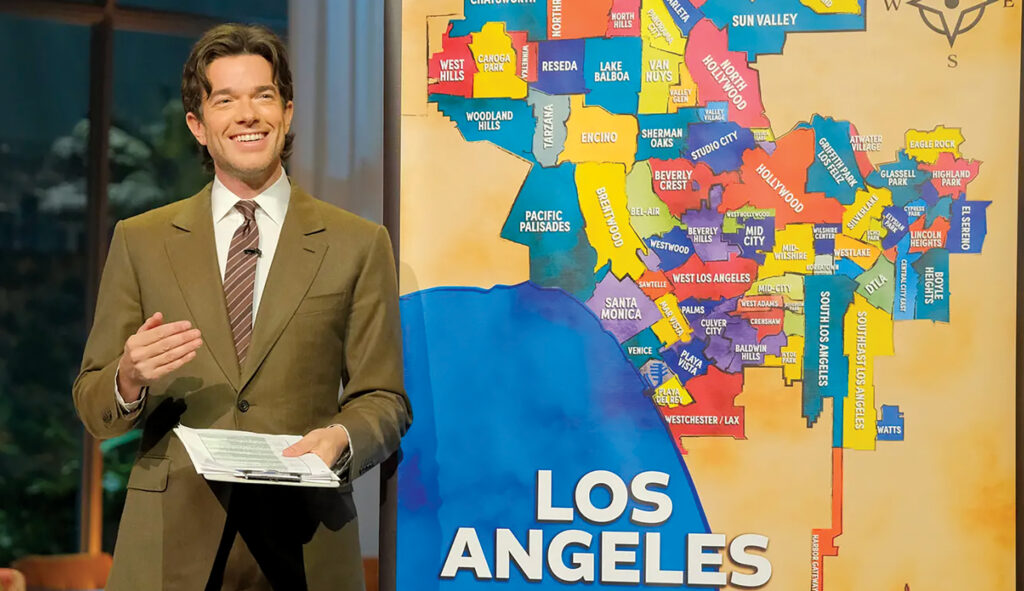

Everybody’s in LA is essentially a variety talk show — complete with a live audience and broadcast to the world without even a Super Bowl-style delay. Assisted by the actor Richard Kind, Mulaney acts as emcee, interviews guests, and does short monologues. There are also live dispatches from other parts of LA, prerecorded segments, and live musical guests. (The first is St. Vincent, performing “Flea.”) The show’s midcentury modern studio, with lots of browns, beiges, and yellows, combined with Mulaney’s penchant for unusually-colored, slightly retro-looking suits, feel like a nod at an older LA and at the show’s throwback format: minus some profanity, much of the material would feel at home in a network studio in the 1970s — or even an auditorium at a 1950s Catskills resort. There’s no Mrs. Maisel, though, and we sometimes feel the lack.

In what could either be a condemnation of Mulaney’s hubris or a testimonial to his gamely professionalism, Everybody’s in LA just barely survives one of the worst comedy premieres I’ve seen. An exercise in gathering and losing steam, the first episode opens with Mulaney sketching out the show’s premise, introducing that episode’s theme (“Coyotes”), and doing a short monologue sketch about Los Angeles and its history as a city “officially founded in 1842 as a place for improv students to go hiking.” He jabs at LA’s different neighborhoods, poor governance (“If you were rolling around town, you’d think, ‘no mayor,’ right?”), and magnetic lure to people elsewhere in the U.S. whose friends told them they were funny.

It’s good, or at least good enough. But the steam engine almost immediately starts to sputter. There’s an awkward sit-down with the R&B singer Ray J, who seems unprepared and, in an off-key, earnest moment, discloses that he’s having relationship problems with his wife. Assisted by a doughty but underwhelming Jerry Seinfeld, Mulaney interviews an expert on coyotes from a wildlife nonprofit group and takes phone calls from Angelenos about their coyote experiences. The phone-ins are, at least, winningly odd.

The comedian Stavros Halkias arrives, perhaps in the nick of time, to shock the audience out of its stupor with a rather off-color joke related to ethnic stereotypes about penis size, though the joke makes everyone uncomfortable and is also slightly dampened by the fact that Halkias’s mic isn’t working so he has to repeat it. He also gets in a funny dig at Mulaney’s drug problems, noting that no one watching the show would think that the polished Mulaney, rather than the slobbish Halkias, was the one who had recently overcome cocaine addiction.

Not everything is falling flat, but it does feel like Mulaney and friends are throwing random ingredients into a stew and hoping for boeuf bourguignon. The jokes also tend toward the inside-baseball: Will Ferrell pops up in the audience to heckle Mulaney while pretending to be the music producer Lou Adler, but the bit feels random, not least because the show’s likely audience of Gen Zers and millennials probably have no idea who Adler is. There’s also a milquetoast prerecorded documentary segment, satirizing HGTV, where a band of Mulaney’s comedian friends (Natasha Leggero and Chelsea Peretti, among others) tour a house that they’re purportedly considering buying together. They wander around making jokes about the decor and accidentally breaking things. My mind also started to wander.

The show feels, at times, like an experiment in “cringe comedy” or anti-humor. There are gestures toward surreality and tonal weirdness — the first episode opens with a brooding Joan Didion quotation, and title cards are accompanied by uneasy synth music — that make one wonder if Mulaney is trying, somewhat halfheartedly, to prove that he can push the artistic envelope in the same way that absurdist docu-comedians like Nathan Fielder and John Wilson have in recent years. If he is, he’s set himself a perhaps unfair challenge: although Wilson’s shows and much of Fielder’s work are ostensibly nonfiction, they’re edited down from hundreds of hours of footage and rigorously produced. They aren’t broadcast live, either.

CLICK HERE TO READ MORE FROM THE WASHINGTON EXAMINER

Everybody’s in LA gets more on track, sort of, in its second episode (“Palm Trees”). Gabriel Iglesias and Jon Stewart join for a roundtable conversation that is funnier, and certainly smoother, than the one in the first. There’s a decent bit where real mental health professionals diagnose stand-up comedians, and a biting sketch envisioning a tutoring clinic founded by Terrence Howard. (Since retiring from acting, Howard has promoted a conspiracist, alternative theory of mathematics he calls “terryology.”) The third episode (“Helicopters”) hosts an interesting conversation with a journalist who pioneered helicopter newsgathering in LA, who recounts with relish how colleagues would use news vehicles disguised as police cars or ambulances to get to news scenes, and Marcia Clark, the lawyer who prosecuted O.J. Simpson.

There’s something admirable in Mulaney’s willingness to lay it all out. Due to deadline constraints, my impressions are drawn only from the first three episodes, though I think I’m (just) intrigued enough to keep watching. Mulaney superfans no doubt will as well. Whether his experimental talk show will resonate with broader audiences is less certain. There’s a reason that the best stand-ups sell out Madison Square Garden while the best improv troupes hope to fill basements: most people want to hear a joke, not watch as the joke is worked out in real time.

J. Oliver Conroy’s writing has been published in the Guardian, New York magazine, the Spectator, the New Criterion, and other publications.