Urban decline is not inevitable or irreversible. It is the result of bad policies, and it can be reversed with good ones. That’s the message of writer-director Matthew Taylor’s new documentary, Gotham: The Fall and Rise of New York. And it’s a message needed now more than ever, as American cities descend once again into 1970s-style lawlessness, insolvency, and decay.

Through interviews with key political players, police officers, business leaders, reporters, and policy wonks, the documentary traces New York City’s decline into a crime-riddled hellscape in the 1970s and its rise into the prosperous “Capital of the World” under the Republican mayorships of Rudy Giuliani and his successor Michael Bloomberg.

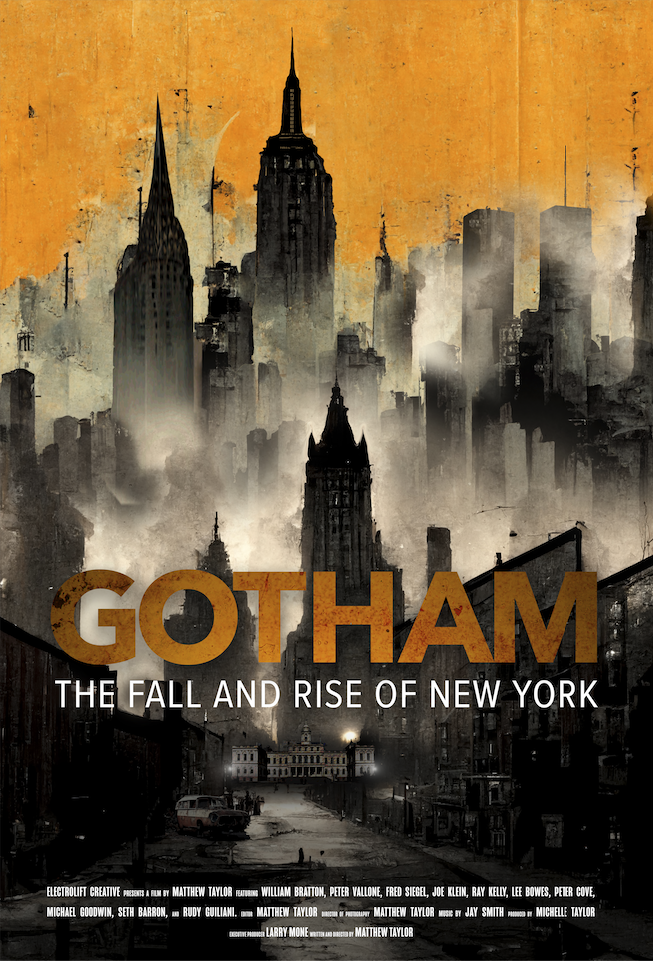

WATCH THE TRAILER:

[embedded content]

Gotham is also a love letter to the Manhattan Institute, New York City’s celebrated policy institute which was the brains behind Giuliani’s reforms. The Institute, the film explains, was founded by disaffected Great Society liberals who realized that their policies were not working according to plan. Instead of clinging to a progressive ideology, they sought real answers to the problems of crime, drug addiction, homelessness, failing schools, and broken families. And they had plenty of evidence all around them of what wasn’t working.

Gotham traces the beginning of the city’s decline to the administration of New York Mayor John Lindsay, a liberal Republican who later switched to the Democratic Party. Lindsay’s big government tax and spend policies pushed the city into a fiscal crisis that griped it for most of the 1970s. But it was his crime policies that really brought the city down.

John Lindsay raises his right hand to take the oath of office as the 103rd Mayor of New York City in December 1965. (Getty Images)

Under Lindsay’s police commissioner, Patrick Murphy, the New York Police Department (NYPD) stopped making narcotics arrests.

“The one thing that was true then and today is the nexus between illegal narcotics activity and violent crime in New York City,” former NYPD chief Louis Anemone explains in the film.

Ordinary New Yorkers could not understand why the police had abandoned them to violent drug-related crimes in their neighborhoods. As the Manhattan Institute’s Heather Mac Donald explains in Gotham, “[Murphy] believed that excusing crime was doing people a favor. It was not.”

The end result was all too predictable – especially for anyone reading the headlines in today’s big Democrat-run cities. Out-of-control crime in the 1970s sent businesses fleeing from New York City, and the taxpayers fled with them. By the end of Lindsay’s term, the city lost about one million people and about 600,000 jobs. This collapse of the tax base brought on a paradoxical crisis for the city’s housing market. The rental market’s collapse meant that housing in the city was too expensive for most people, but there was also mass abandonment of residential structures due to foreclosures, which in turn created large scale urban blight.

View across a trash-strewn vacant lot of abandoned buildings in a South Bronx neighborhood of New York City in 1976. (Brownie Harris/Corbis via Getty Images)

In the midst of this crime-fueled crisis, the city laid off 25 percent of its police force due to the ongoing fiscal crisis. Of course, the lack of policing only made the situation worse. The city became even more dysfunctional and unsafe.

The city’s fall was relatively fast. Its rise would span multiple administrations, but the film unabashedly gives credit where it’s due to the two-term administration of Mayor Rudy Giuliani. But first, there was Mayor Ed Koch’s term from 1978-1989. Koch—a moderate Democrat or, as he liked to call himself, a “sane liberal”—was able to pull the city back from its fiscal crisis, thanks in no small part to the economic boom brought on by President Ronald Reagan’s policies. The Wall Street of the 1980s grabbed the city by the hand and pulled it away from a fiscal cliff.

New York City Mayor Ed Koch rides the local subway train to Brooklyn on August 2, 1983. (Dan Goodrich/Newsday RM via Getty Images)

The 1980s also saw the beginning of a revitalization of the city’s blighted areas due to a policy of privatization. Areas around Bryant Park and Grand Central Station, for example, were put under the control of private businesses that cleaned them up, policed them, and ensured that graffiti and trash were removed. The difference was felt immediately. These areas were safe again for people to enjoy. Urban blight is a magnet for crime and decay, Gotham demonstrates. Cleaning up the blight is the first step in reclaiming a city for civilization.

In 1986, Mayor Koch announced a $5.4 billion fund to renovate or build 252,000 units of affordable housing in the city. This was a major step in creating the conditions to re-populate New York. But Koch, like Mayor David Dinkins after him, was unable to make a dent in the city’s crime problem. Finally, the public outcry over a number of high-profile criminal cases during Dinkins’ mayorship led to the passage of a law that dramatically increased the city’s police force. But the beneficiary of this new and stronger force would be Dinkins’ successor, Rudy Giuliani.

New York City Mayor David Dinkins (left) and Mayor-elect Rudolph Giuliani shake hands on the steps of City Hall on November 3, 1993, a day after Giuliani defeated Dinkins in the mayoral race. (DON EMMERT/AFP via Getty Images)

Giuliani had lost to Dinkins when he ran for mayor the first time in 1990. He spent the three years following his defeat schooling himself in the problems facing the city and creating a plan of action to deal with them. In doing so, he relied heavily on the data-driven research of the Manhattan Institute.

His first smart move was appointing William Bratton as his police commissioner. Bratton had distinguished himself as the chief of the Transit Police (at the time, the NYPD was split into three separate departments: the Transit Police, the Housing Police, and the City Police). He had studied social scientists James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling’s “broken windows” theory, which held that signs of urban disorder—broken windows, graffiti, loitering, vandalism, public drinking, jaywalking, petty crime—created an atmosphere of lawlessness that fed and encouraged more violent crime. The theory goes that one broken window leads to multiple broken windows, and soon you have a blighted and unsafe neighborhood.

As chief of the Transit Police, Bratton decided to crack down on the petty crime of turnstile jumping. He soon discovered that the people who jump turnstiles overwhelmingly had prior criminal records and often had knives and guns on them. In other words, they were jumping the turnstiles on their way to commit a bigger crime of robbery and/or murder. By cracking down on the people trying to cheat the subway fare, Bratton brought down subway crime by double digits in the span of two years.

As Giuliani’s police commissioner, Bratton brought this “broken windows” approach to the entire city. He cracked down on petty crimes and nuisance crimes and then tackled the larger ones. He was also helped by reforms Giuliani put in place that united the Transit, Housing, and City police departments into one united force. This helped because in the past these three separate departments were often hunting down the same criminal but not communicating with each other.

Police Commissioner William Bratton (left) and Mayor Rudy Giuliani at an event in New York City June 28, 1995. (Allan Tannenbaum/Getty Images)

Giuliani also tackled the issue of pickpockets and muggings—particularly in Times Square. The method was simple: He put mounted police on the street who were up high enough to have a full view of an area. Then he put undercover cops in plain clothes (with earpieces to communicate) throughout the shopping area. The cop on the horse would tell the undercover cops on the ground where a pickpocket or mugging or potential kidnapping was taking place, and the cops on the ground would nab the bad guys. In a matter of months, crime in Time Square dropped by half, then by 75 percent, and then it virtually disappeared. Under Giuliani’s leadership, Time Square went from being a seedy crime-plagued area to a family-friendly tourist trap.

As Gotham explains, the key to many of these crime reforms was a database Giuliani’s administration created called CompStat that allowed them to track where, when, and what crimes were being committed in the city. This allowed the police to see patterns in crimes. For example, they discovered that 10 percent of the city accounted for over 60 percent of the crime. This allowed them to use their resources more effectively.

New York mounted police officer in Times Square in 1997. (Elise HARDY/Gamma-Rapho via Getty Images)

Police officers stand in front of the New York Police Department in Times Square on December 30, 1999. (Erik Freeland/CORBIS SABA/Corbis via Getty Images)

They also learned that 75 percent of the subway crimes were committed on the platforms, not in the subway cars. At the time, police had only been patrolling the subways cars. By moving them onto the platforms, the city cut subway crime in half in a matter of weeks.

Giuliani also held police commanders responsible for the crime in their areas. They had to explain why they were not using the CompStat data. They could no longer ignore crimes—including drug-related crimes. Police were now actively encouraged and even ordered to deal with the drug crimes.

All of these reforms were designed to focus the police on addressing “quality of life offenses” (i.e., loitering, graffiti, vandalism, panhandling, petty theft, etc.) instead of just responding to crime. This meant getting cops out of their squad cars and onto the neighborhood streets.

As Bratton, who is interviewed in Gotham, explains, “Quality of life offenses are as important as serious crime to be addressed. The basic mission for which the police force exists is to prevent crime and disorder—the five most important words in law enforcement. To deal effectively with crime, you’re also at the same time going to have to deal with disorder.”

While the university sociology departments and progressive think tanks were concerned about the “root causes” of crime, Giuliani and Bratton were concerned about ending it.

“I believe the cause of crime is people,” Bratton says. “By focusing on the small things, that often times disrupted the bigger things from happening. By going after quality of life, we were also having an impact on crime.”

The end result: by the time Bratton left as police commissioner, crime was down 39 percent. By the end of Giuliani’s first term as mayor, he had reduced murder in the city by over 65 percent. Ordinary New Yorkers didn’t need to read the stats. They could see the change. The city was safe again. People could see it in their neighborhoods.

Former NYC Police Commissioner William “Bill” Bratton stands in the subway entrance in Times Square on January 29, 1998. (Tom Herde/The Boston Globe via Getty Images)

“You had neighborhoods that had become so safe that you had two-parent families moving in,” Heather Mac Donald explains. “That brought stability that [was] eyes on the street, that [was] serving the role of police officers. Police is always the second-best solution to urban disorder. The best solution is families.”

All of this is an object lesson for the current crime and disorder gripping American cities — especially as we see politicians embracing the destructive policies of the past. It took over 20 years to create a low-crime New York City, but it took an astonishingly short amount of time to reverse course.

Still, Gotham offers a hopefully vision. In the ‘70s and ‘80s, no one believed New York City could be saved. Giuliani, Bloomberg, the NYPD, civil servants, business leaders, the Manhattan Institute, and civic-minded New Yorkers proved all of the naysayers wrong.

“The experience of the Giuliani term was the result of real efforts and real ideas by real people,” the Manhattan Institute’s former president Larry Mone says in Gotham. “It didn’t just happen. And if you don’t really understand that legacy, you’re doomed to watch it fall apart before your very eyes.”

Gotham: The Fall and Rise of New York is available to stream, rent, or buy at iTunes, Amazon Prime, GooglePlay, Vimeo, Vudu, and YouTube. Click here for more information.

Rebecca Mansour is Senior Editor-at-Large for Breitbart News. Follow her on Twitter at @RAMansour.