WASHINGTON, DC – Texas and Louisiana lack standing to sue the Biden administration’s policy of not enforcing a federal law requiring the arrest of certain criminal aliens, the Supreme Court held on Friday.

Justice Brett Kavanaugh wrote the majority opinion for justices, examining 8 U.S.C. § 1226, where Congress commands that the Department of Homeland Security “shall” arrest and detain some types of criminal aliens when they are released from state prison. Secretary Alejandro Mayorkas has refused to enforce that law.

“In 2021, after President Biden took office, the Department of Homeland Security issued new Guidelines for immigration enforcement,” Kavanaugh began. “The Guidelines prioritize the arrest and removal from the United States of noncitizens who are suspected terrorists or dangerous criminals, or who have unlawfully entered the country only recently, for example.”

“The States essentially want the Federal Judiciary to order the Executive Branch to alter its arrest policy so as to make more arrests,” he continued. “But this Court has long held that a citizen lacks standing to contest the policies of the prosecuting authority when he himself is neither prosecuted nor threatened with prosecution. Consistent with that fundamental Article III principle, we conclude that the States lack Article III standing to bring this suit.”

Texas DPS troopers apprehend two criminal aliens and seize smuggled marijuana near the border with Mexico. (Texas Department of Public Safety)

“Under Article II, the Executive Branch possesses authority to decide how to prioritize and how aggressively to pursue legal actions against defendants who violate the law,” the majority added.

“That principle of enforcement discretion over arrests and prosecutions extends to the immigration context, where the Court has stressed that the Executive’s enforcement discretion implicates not only normal domestic law enforcement priorities but also foreign-policy objectives,” Kavanaugh also wrote.

Kavanaugh added the caveat that:

the standing calculus might change if the Executive Branch wholly abandoned its statutory responsibilities to make arrests or bring prosecutions. Under the Administrative Procedure Act, a plaintiff arguably could obtain review of agency non-enforcement if an agency has consciously and expressly adopted a general policy that is so extreme as to amount to an abdication of its statutory responsibilities.

“To be clear, our Article III decision today should in no way be read to suggest or imply that the Executive possesses some freestanding or general constitutional authority to disregard statutes requiring or prohibiting executive action,” he also cautioned.

“It bears emphasis that the question of whether the federal courts have jurisdiction under Article III is distinct from the question of whether the Executive Branch is complying with the relevant statutes,” the majority added. “We take no position on whether the Executive Branch here is complying with its legal obligations.”

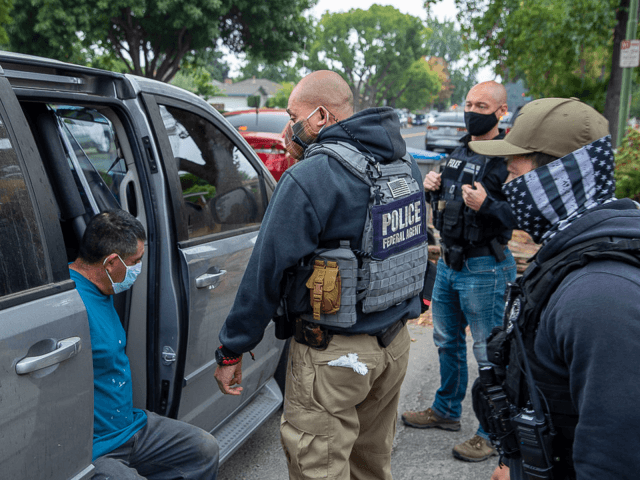

The Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) announced the conclusion to a week-long targeted enforcement operation that resulted in the apprehension of over 125 at-large criminal aliens across the state of California (ICE)

The majority concluded by observing that “Congress possesses an array of tools to analyze and influence those policies,” and that “through elections, American voters can both influence Executive Branch policies and hold elected officials to account for enforcement decisions.”

Justice Neil Gorsuch, joined by Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett, agreed that the states lack standing here, but refused to join Kavanaugh’s opinion for Chief Justice John Roberts and the three liberal justices, writing an entirely separate analysis that concluded:

In our system of government, federal courts play an important but limited role by resolving cases and controversies. Standing doctrine honors this limitation at the front end of every lawsuit. It preserves a forum for plaintiffs seeking relief for concrete and personal harms while filtering out those with generalized grievances that belong to a legislature to address. Traditional remedial rules do similar work at the back end of a case. They ensure successful plaintiffs obtain meaningful relief. But they also restrain courts from altering rights and obligations more broadly in ways that would interfere with the power reserved to the people’s elected representatives. In this case, standing and remedies intersect. The States lack standing because federal courts do not have authority to redress their injuries. Section 1252(f )(1) [of federal immigration law] denies the States any coercive relief. A vacatur order under §706(2) [of another federal law] supplies them no effectual relief. And such an order itself may not even be legally permissible. The States urge us to look past these problems, but I do not see how we might. The Constitution affords federal courts considerable power, but it does not establish “government by lawsuit.”

Justice Samuel Alito dissented from the court’s 8-1 judgment, writing separately to explain why he thought states do have standing in court under these circumstances.

The case is United States v. Texas, No. 22-58 in the Supreme Court of the United States.

Breitbart News senior legal contributor Ken Klukowski is a lawyer who served in the White House and Justice Department.