By Ruchir Sharma, chair of Rockefeller International

In a historic turn, China’s rise as an economic superpower is reversing. The biggest global story of the past half century may be over.

After stagnating under Mao Zedong in the 1960s and 70s, China opened to the world in the 1980s — and took off in subsequent decades. Its share of the global economy rose nearly tenfold from below 2 per cent in 1990 to 18.4 per cent in 2021. No nation had ever risen so far, so fast.

Then the reversal began. In 2022, China’s share of the world economy shrank a bit. This year it will shrink more significantly, to 17 per cent. That two-year drop of 1.4 per cent is the largest since the 1960s.

These numbers are in “nominal” dollar terms — unadjusted for inflation — the measure that most accurately captures a nation’s relative economic strength. China aims to reclaim the imperial status it held from the 16th to early 19th centuries, when its share of world economic output peaked at one-third, but that goal may be slipping out of reach.

China’s decline could reorder the world. Since the 1990s, the country’s share of global GDP grew mainly at the expense of Europe and Japan, which have seen their shares hold more or less steady over the past two years. The gap left by China has been filled mainly by the US and by other emerging nations.

To put this in perspective, the world economy is expected to grow by $8tn in 2022 and 2023 to $105tn. China will account for none of that gain, the US will account for 45 per cent, and other emerging nations for 50 per cent. Half the gain for emerging nations will come from just five of these countries: India, Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil and Poland. That is a striking sign of possible power shifts to come.

Moreover, China’s slipping share of world GDP in nominal terms is not based on independent or foreign sources. The nominal figures are published as part of their official GDP data. So China’s rise is reversing by Beijing’s own account.

One reason this has gone largely unnoticed is that most analysts focus on real GDP growth, which is inflation-adjusted. And by adjusting creatively for inflation, Beijing has long managed to report that real growth is steadily hitting its official target, now around 5 per cent. This in turn appears to confirm, every quarter, the official story that “the east is rising.” But China’s real long-term potential growth rate — the sum of new workers entering the labour force and output per worker — is now more like 2.5 per cent.

The ongoing baby bust in China has already lowered its share of the world working age population from a peak of 24 per cent to 19 per cent, and it is expected to fall to 10 per cent over the next 35 years. With a shrinking share of the world’s workers, a smaller share of growth is almost certain.

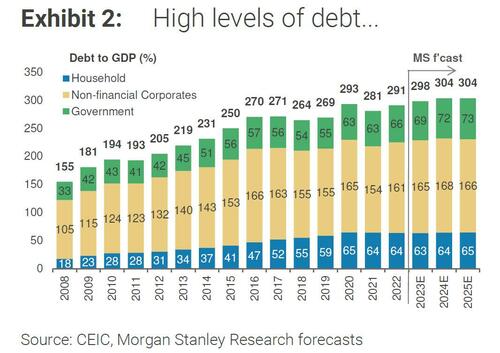

Further, over the past decade, China’s government has grown more meddlesome, and its debts are historically high for a developing country. These forces are slowing growth in productivity, measured as output per worker. This combination — fewer workers, and anaemic growth in output per worker — will make it difficult in the extreme for China to start winning back share in the global economy.

In nominal dollar terms, China’s GDP is on track to decline in 2023, for the first time since a large devaluation of the renminbi in 1994. Given the constraints to real GDP growth, in the coming years Beijing can only regain global share with a spike in inflation or in the value of the renminbi — but neither is likely. China is one of the few economies suffering from deflation, and it also faces a debt-fuelled property bust, which typically leads to a devaluation of the local currency.

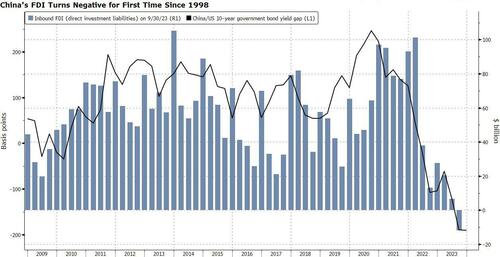

Investors are pulling money out of China at a record pace, adding to pressure on the renminbi. Foreigners cut investment in Chinese factories and other projects by $12bn in the third quarter — the first such drop since records began. Locals, who often flee a troubled market before foreigners do, are leaving too. Chinese investors are making outward investments at an unusually rapid pace and prowling the world for real estate deals.

China’s President Xi Jinping has in the past expressed supreme confidence that history is shifting in his country’s favour, and nothing can stop its rise. His meetings with Joe Biden and US chief executives at last week’s summit in San Francisco did hint at moderation, or at least a recognition that China still needs foreign business partners. But almost no matter what Xi does, his nation’s share in the global economy is likely to decline for the foreseeable future.

It’s a post-China world now.

By Ruchir Sharma, chair of Rockefeller International

In a historic turn, China’s rise as an economic superpower is reversing. The biggest global story of the past half century may be over.

After stagnating under Mao Zedong in the 1960s and 70s, China opened to the world in the 1980s — and took off in subsequent decades. Its share of the global economy rose nearly tenfold from below 2 per cent in 1990 to 18.4 per cent in 2021. No nation had ever risen so far, so fast.

Then the reversal began. In 2022, China’s share of the world economy shrank a bit. This year it will shrink more significantly, to 17 per cent. That two-year drop of 1.4 per cent is the largest since the 1960s.

These numbers are in “nominal” dollar terms — unadjusted for inflation — the measure that most accurately captures a nation’s relative economic strength. China aims to reclaim the imperial status it held from the 16th to early 19th centuries, when its share of world economic output peaked at one-third, but that goal may be slipping out of reach.

China’s decline could reorder the world. Since the 1990s, the country’s share of global GDP grew mainly at the expense of Europe and Japan, which have seen their shares hold more or less steady over the past two years. The gap left by China has been filled mainly by the US and by other emerging nations.

To put this in perspective, the world economy is expected to grow by $8tn in 2022 and 2023 to $105tn. China will account for none of that gain, the US will account for 45 per cent, and other emerging nations for 50 per cent. Half the gain for emerging nations will come from just five of these countries: India, Indonesia, Mexico, Brazil and Poland. That is a striking sign of possible power shifts to come.

Moreover, China’s slipping share of world GDP in nominal terms is not based on independent or foreign sources. The nominal figures are published as part of their official GDP data. So China’s rise is reversing by Beijing’s own account.

One reason this has gone largely unnoticed is that most analysts focus on real GDP growth, which is inflation-adjusted. And by adjusting creatively for inflation, Beijing has long managed to report that real growth is steadily hitting its official target, now around 5 per cent. This in turn appears to confirm, every quarter, the official story that “the east is rising.” But China’s real long-term potential growth rate — the sum of new workers entering the labour force and output per worker — is now more like 2.5 per cent.

The ongoing baby bust in China has already lowered its share of the world working age population from a peak of 24 per cent to 19 per cent, and it is expected to fall to 10 per cent over the next 35 years. With a shrinking share of the world’s workers, a smaller share of growth is almost certain.

Further, over the past decade, China’s government has grown more meddlesome, and its debts are historically high for a developing country. These forces are slowing growth in productivity, measured as output per worker. This combination — fewer workers, and anaemic growth in output per worker — will make it difficult in the extreme for China to start winning back share in the global economy.

In nominal dollar terms, China’s GDP is on track to decline in 2023, for the first time since a large devaluation of the renminbi in 1994. Given the constraints to real GDP growth, in the coming years Beijing can only regain global share with a spike in inflation or in the value of the renminbi — but neither is likely. China is one of the few economies suffering from deflation, and it also faces a debt-fuelled property bust, which typically leads to a devaluation of the local currency.

Investors are pulling money out of China at a record pace, adding to pressure on the renminbi. Foreigners cut investment in Chinese factories and other projects by $12bn in the third quarter — the first such drop since records began. Locals, who often flee a troubled market before foreigners do, are leaving too. Chinese investors are making outward investments at an unusually rapid pace and prowling the world for real estate deals.

China’s President Xi Jinping has in the past expressed supreme confidence that history is shifting in his country’s favour, and nothing can stop its rise. His meetings with Joe Biden and US chief executives at last week’s summit in San Francisco did hint at moderation, or at least a recognition that China still needs foreign business partners. But almost no matter what Xi does, his nation’s share in the global economy is likely to decline for the foreseeable future.

It’s a post-China world now.

Loading…