(function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v3.0”; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’)); –>

–>

September 6, 2023

I have been severely deaf since my early teens. I was and am one of the fortunate ones: not having been challenged with a sense deprivation before benefiting from an excellent primary and secondary education. This blessing enabled me to acceptably perform through writing and verbal skills at an advanced level and made a critical difference in my life’s independence and work.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”); } }); }); }

I was mostly deaf through university but squeaked by on my papers. I was mostly deaf when I started working but faked it for the early years, as the focus of my work was, necessarily, writing and research. In my late twenties I resigned myself to accept a fitting for hearing aids. The aids, though not flattering, were a help in one ear, but not a solution. However, I had managed to learn, through trial and error, to lip-read. I had also identified and put to work the sort of empathetic, “internal” personal attention to the speaker — another kind of “listening” — that the life of Helen Keller so beautifully exemplifies.

I worked on the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA) when returning in the early ’80s to D.C., and with a young daughter to support. Soon after the ADA became federal law, I at last would tell my prospective employers that I had severe hearing loss. (I had exhausted my pretense of understanding what I did not hear, especially at the larger meetings — which could have been my undoing.) But by then, my résumé was strong enough to gamble on being hired anyway, and I usually was. One of my semi-humorous confessions, to people close to me and knowing my deafness, was, “It was awful — she said her grandmother just died, and I said, ‘Great!'”

Mr. Rocky Stone, profoundly deaf since childhood, was a pioneer disability advocate. I worked for him — first on the fledgling ADA legislation before its passage in 1990, subsequently in getting the word out on the rights we were finally to be granted. Rocky had retired from his career in the federal bureaucracy and was by then the leading advocate for the hard of hearing.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”); } }); }); }

Were he still with us, Rocky would have had a lot to say about masks, COVID, and deafness. He told me, quite pointedly, at our first meeting that deafness is the only invisible disability. He said the unique feature of deafness qua disability is in a general public reluctance to accept deafness in another, on the face of it: if you can’t see a disability on someone, it’s not there. I was struck by his words, as I knew them to be true by my own experience.

Invisible or not, the stress and routine, the sheer difficulty of any disability is overlooked and minimized and even ridiculed by an astonishing number of people. Even those who sympathize will at times exhibit, usually unintentionally, a degree of intolerance or reluctance to naturally engage with the disabled.

Fast-forward to mid-summer of 2021, with the country deep in the COVID nightmare, when a majority of the states had mask mandates in effect. I am at my grocery chain store, masked up. Because I lip-read, I cannot “hear” the teller talking to me because her lips are masked. I explain to her that I am deaf, and I lip read, and I ask, can she speak up a little, and distinctly. She starts yelling at me. She shrugs, she glares, she indicates that I am trying to force her to take her mask off. So that I can hear her.

And what if one were legally blind? The blind use their senses of smell and hearing to direct themselves in public, with or without guide dogs. What if I were in a wheelchair? Can we really suppose that someone coping with the public from a few feet off the ground is not further challenged by wearing and trying to breathe around a mask and understanding/dealing with anyone else’s issues? How about breathing and asthma? That’s just part of a list.

Childhood intellectual and cognitive disabilities — including first learning to talk! — have increasingly been associated with the COVID mask mandates.

The disabled make up about 13% of the U.S. population. This number includes those with hearing, vision, cognitive, walking, self-care, and independent living difficulties. The percentage increases to 46% for Americans 75 and older. Of this population, 41% are reported as having experienced high levels of psychological distress during COVID.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”); } }); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

The 2020–2021 mask mandates for COVID have now been deemed ineffective by a growing number of experts. Yet millions of the disabled in the United States were hit with the mask mandates, with absolutely no public conversation regarding special status, no consideration of exemption; even no allowance for the probable difficulties to be forced upon the disabled: the routinely increased stress, the judgmental hostility in many cases, the legal and institutional threats, even the danger — of having our senses, our mobility, and even survival in some cases further compromised.

Just as the ADA legislation, a civil rights issue to be sure, came to the U.S. shockingly late, worse and far later came any awareness, consideration, or responsibility for the problems with the masking for COVID vis-à-vis our most vulnerable populations. If in fact the mandated masks for COVID were as ineffective as many now claim, that is a grievous error — and one not to be repeated. Yet even more grievous, maybe damnably so, is the recent coy beginnings of prevarication on the part of our government and quasi-governmental “scientific” elite, who now murmur — even with a return of COVID in arguably remote view — about putting the masks back on the American public.

Dr. Fauci is on his media tour again, with his familiar opinions. He’s worried the American people won’t step up to the masks. If Fauci is, in fact and truly, worried about the public rejecting masks — a ghastly COVID reprise of our past but never forgotten nightmare — I imagine that many Americans, to include many of the disabled, are a hell of a lot more worried about putting them back on again.

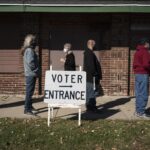

Image via Pexels.

<!–

–>

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>