President Joe Biden is hitting the campaign trail in a slightly unorthodox way as he tries to help Democrats hang on to their slender congressional majorities in an election where they are at risk of a historic wipeout.

Biden is eschewing traditional campaign rallies and allowing vulnerable Democrats to avoid photo-ops that would likely further endanger them. But he is not staying holed up in the White House basement either, staying above the fray and avoiding headlines. He is attempting a delicate balance between throwing down-ballot Democrats a lifeline and tying them to an unpopular administration.

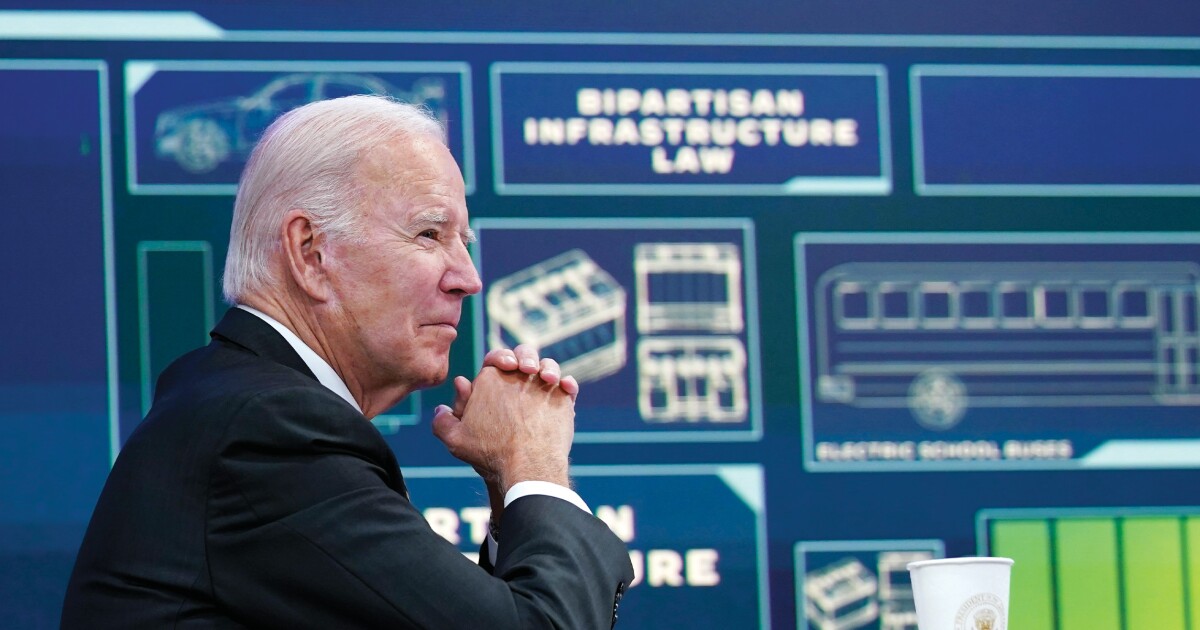

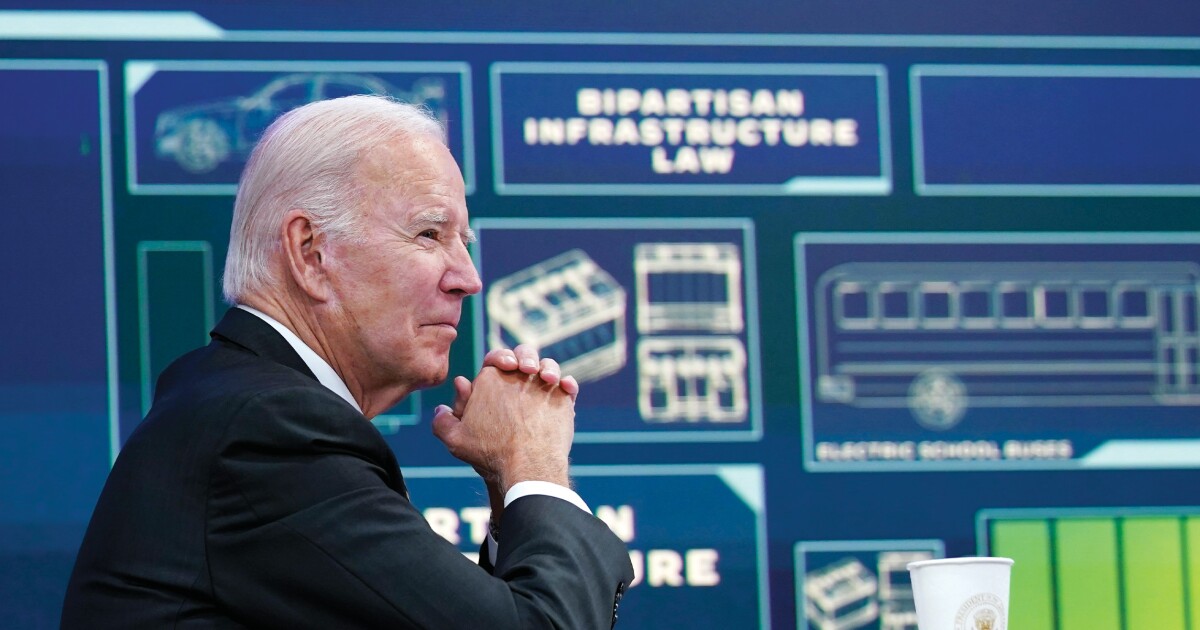

The president has been leveraging the power of his office by using executive order signings as an occasion to visit states where allies are on the ballot. He has also gone on a promotional tour advertising the benefits of various spending bills he has signed into law, which not so coincidentally fall in the backyards of those who are up for election, unlike himself.

Biden headlines Democratic National Committee fundraisers behind closed doors, avoiding the optics of sparsely attended public events or awkward grin-and-grips with candidates. But the appearances still allow him to raise money and give widely covered speeches amplifying the party’s main midterm election themes: the specter of former President Donald Trump and “MAGA” Republicans, dangers to democracy, the Supreme Court reversing Roe v. Wade and threatening other privacy rights, and the hypocrisy of GOP lawmakers who “vote no and take the dough” from his favored spending packages.

Case in point: Biden headed to Pittsburgh to tout the projects that would be funded by the bipartisan infrastructure law he signed last year. Then he trekked over to Philadelphia for a reception with Lt. Gov. John Fetterman, who is locked in a tight Senate race with Republican opponent Dr. Mehmet Oz.

Biden also went out to the West Coast. While more safely Democratic than the Senate swing state of Pennsylvania, Oregon’s gubernatorial election and several California House races are competitive. In Irvine, he signed an executive order aimed at lowering prescription drug costs and assailed GOP lawmakers for unanimously voting against the Inflation Reduction Act — “If Republicans take control, the prices are going to go up,” he claimed — with Rep. Katie Porter (D-CA).

The day before, Biden was in Colorado. He delivered a speech extolling the virtues of national monuments, and by the area around Camp Hale that he made over 400 square miles off-limits to gas and oil drilling in a state that is green-friendly — but not so reliably blue that Sen. Michael Bennet (D-CO), up for reelection this year, can afford to sleep on his GOP challenger.

But there are limits to how far Biden is willing to go with his strategy of wielding presidential power in the light of day and hobnobbing with DNC donors behind closed doors, often at night. Notice that his itinerary skipped Arizona and Nevada, which feature two of the closest Senate races in the country. At this writing, he hasn’t been to Georgia in weeks. He is headed to Florida, however, where polling suggests statewide races that are competitive but not quite so tight.

The White House balks at this characterization of Biden’s campaign schedule. “He’s been on the road nonstop, and he will continue to be on the road nonstop,” protested press secretary Karine Jean-Pierre, who said the Hatch Act constrains her from delving too deeply into the president’s midterm activities. “And, you know, where he is needed, he will go.”

“It’s really a way to make the best of a bad situation,” a veteran Democratic strategist told the Washington Examiner. Biden, who was mostly able to avoid large-scale public events in 2020 because of the pandemic, is ranging between 39% and 46% job approval ratings in public polls. He is underwater by more than 10 points in the RealClearPolitics average. His numbers in many swing states are even worse.

The president can remind Democrats that some legislation has passed while the party has enjoyed unified control of the federal government; that more can pass, including filibuster reform, with as few as two additional Democratic-held Senate seats; that nothing much will pass if Republicans take even one chamber of Congress; that Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization happened. He can’t get voters who disapprove of his performance in the White House to vote for the Democratic ticket, however.

Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump each held a dozen or more rallies in the month before their first midterm elections. Those were, however, major defeats for their respective parties. That’s what Biden is trying to avoid. Time will tell if he actually can.