–>

April 30, 2023

On March 28—just two days before the congressionally proclaimed “National Vietnam War Veteran’s Day“—PBS broadcast “The Movement and the ‘Madman,’” gleefully depicting America’s resistance to blatant international Communist aggression in Vietnam as moronic and portraying leaders of the so-called “peace movement” as heroes who saved the world from nuclear disaster. The program was as absurd as it was shameful.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); }

Jefferson advised that, when angry, count to 10 before speaking. When very angry, count to 100. Waiting a month did not quell my outrage, but today’s forty-eighth anniversary of the Communist conquest of South Vietnam necessitated a response.

I spent considerable time in Vietnam between 1968 and leaving during the 1975 final evacuation, including tours as an Army Lieutenant and Captain, a stint as a journalist, and multiple visits while serving as national security adviser to a member of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee. After leaving the Army, I was a fellow at Stanford’s Hoover Institution, where I authored the first major English-language history of Vietnamese Communism.

Beginning in 1965, I took part in more than 100 debates, lectures, ‘teach-ins,” and other programs on the war. During that time, I encountered a litany of arguments against the war from some of the most prominent war critics in the country. Most of their alleged “facts” were clearly false—a point confirmed by the “Pentagon Papers.”

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); }

Their protests were hardly meaningless. They helped Hanoi “snatch defeat from the jaws of victory” when America and its allies were clearly winning the war on the battlefield—paving the way for the slaughter of millions and the loss of any chance of freedom for tens of millions more in Indochina alone. The consequences beyond those borders included wars in Angola, Afghanistan, and Central America—and a credible case can be made that they incentivized Osama bin Laden to attack America on September 11, 2001.

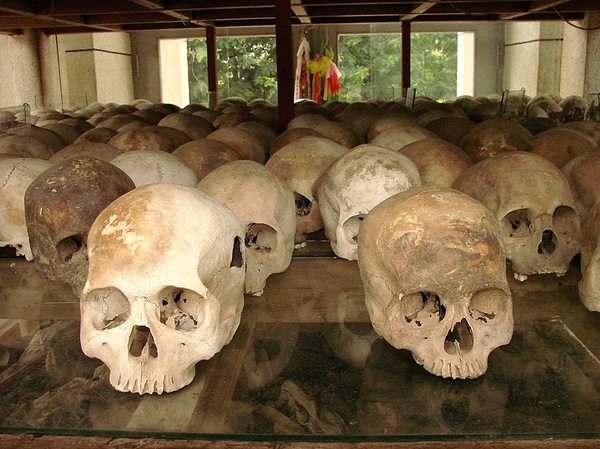

Image: Human remains from Cambodia’s killing fields by Adam Jones. CC BY-SA 3.0.

PBS did not even address why American involvement in Vietnam was so inherently evil. Most of the substantive arguments it made seemed premised upon the reality that soldiers and civilians were dying—a common occurrence during armed conflicts and, certainly, a much stronger argument for abandoning our resistance to Nazi Germany and Imperial Japan during World War II, which claimed tens of millions more lives.

There was not a single reference to Hanoi’s postwar publication of its official history—translated into English under the title Victory in Vietnam—documenting its May 1959 decision to open the Ho Chi Minh Trail and smuggle troops, weapons, and supplies through Laos and Cambodia into South Vietnam to overthrow its government by armed force. Put simply, Hanoi demolished the claim by war critics that America was not resisting international aggression in Vietnam.

It is true that the 1954 partition of Vietnam was supposed to be temporary. But the same is true of the 1945 division of Korea. When North Korea invaded South Korea in 1950, the UN Security Council denounced the aggression and authorized the United States to lead a multinational coalition under the UN flag to protect South Korea.

Several speakers during the hour-long program asserted that their protests kept President Nixon from using nuclear weapons against North Vietnam. The apparent basis for that dubious premise was an “options paper” prepared for the president, including a wide range of contingencies. Nixon told close advisers that he wanted to force Hanoi to the negotiating table by making them fear that he was a “madman” who might use nuclear weapons—an option Nixon had expressly dismissed while campaigning.

It should be recalled that Nixon served as vice president under Dwight Eisenhower, who reportedly helped end the Korean War by leaking word to China through Indian diplomats that he was moving nuclear weapons to Okinawa for possible use against North Korea if a quick settlement could not be reached. Not everyone agrees that these threats were ever actually delivered, but even deniers generally acknowledge the assertions made about these threats. Decades later, former Secretary of State Colin Powell admitted that he had tried to deter Saddam Hussein’s 1990 aggression by hinting that America might use nuclear weapons.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

Typical of the outrageous misrepresentation in this pathetic propaganda piece was its identification of Cora Weiss as a “peace activist” anxious to make protests safe for families. There was no reference to the fact that Ms. Weiss had served as Hanoi’s agent in efforts to blackmail the families of American POWs by promising mail and better treatment for their loved ones if they would publicly denounce the war. “Peace activist,” my ass—that was constitutional Treason!

Near the end of the program, various speakers lamented that their protests had accomplished very little—but at least had saved lives. Both claims are patently false.

Militarily, by 1969 Hanoi was on the ropes. Despite misreporting by the American media, the 1968 Tet Offensive was a military defeat for the Communists. All their attacks were repulsed, and their forces suffered more than ten times U.S. and South Vietnamese casualties. For the rest of the war, the puppet “Viet Cong” virtually ceased to exist as a fighting force. All the major fighting thereafter was done by North Vietnamese regulars.

But the “peace movement” encouraged Hanoi to hang on, and ultimately persuaded a feckless Congress in 1973 to make it illegal to spend appropriated funds for U.S. troops to try to fulfill the solemn pledge the United States had made in the 1955 SEATO Treaty—ratified with but a single dissent in the Senate and reaffirmed by 99.6% of Congress in authorizing war at the time of the 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident. Put simply, the “peace movement” was the most decisive factor in the Communist victory in Indochina.

Perhaps the most absurd comment came from “peace activist” Susan Miller, who claimed the protests had “saved people’s lives.” Space will not permit a full discussion of how wrong she was, but after Congress threw in the towel and the Communists conquered South Vietnam and its neighbors behind columns of Soviet-made tanks, more people died throughout Indochina than had died in combat during the previous 14 years.

In tiny Cambodia alone, the Yale University Cambodian Genocide Program concluded that Pol Pot’s Khmer Rouge (“Red Cambodians”) was responsible for the deaths of more than 20% of the population–about 1.7 million human beings. National Geographic Today noted in a 2003 story on the “killing fields” that, to save bullets, small children were dispatched by picking them up by their legs and “battered them against trees.”

The UN High Commissioner on Refugees estimated that as many as 400,000 South Vietnamese perished as “boat people” while fleeing their country in unseaworthy vessels. Countless thousands more were executed or died in “Reeducation Camps” and “New Economic Zones.” As for human rights, the distinguished human rights organization Freedom House observed in 1978 that the unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam was “as free as Korea (North), less free than China (Mainland).” p. 321. Thank you, American “peace movement!”

Given the tragic realities of what happened and Hanoi’s admissions that, in reality, it was engaging in armed international aggression, I find it shocking that PBS is hosting anti-Vietnam protesters today to brag about their behavior. If they had any decency, they would hide their faces in shame.

Professor Turner holds both professional and academic doctorates from the University of Virginia, where prior to his 2020 retirement, he cotaught interdisciplinary postgraduate seminars on Vietnam for three decades.

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>