(function(d, s, id) { var js, fjs = d.getElementsByTagName(s)[0]; if (d.getElementById(id)) return; js = d.createElement(s); js.id = id; js.src = “https://connect.facebook.net/en_US/sdk.js#xfbml=1&version=v3.0”; fjs.parentNode.insertBefore(js, fjs); }(document, ‘script’, ‘facebook-jssdk’)); –>

–>

November 23, 2023

Perhaps no year in American history has been more pivotal or historically significant than 1863. That year, the nation had been torn in half, with the seceded Confederate States remaining embroiled in the midst of the great Civil War. In the early summer of that year, the nation witnessed the climactic battle of Gettysburg.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268089992-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3028”); } }); }); }

Gettysburg concluded on July 3, 1863, with Robert E. Lee’s tattered Confederate Army of Northern Virginia retreating south, on July 4, Independence Day, after a disastrous military maneuver at Gettysburg that has become known as Pickett’s Charge.

Some military historians refer to Pickett’s Charge as the “high watermark of the Confederacy.” On July 4, the very day that Lee retreated back into Virginia, his future rival in battle, General Ulysses S. Grant, defeated the Confederate Army at Vicksburg on Independence Day, effectively securing two major victories for the Union Army within a matter of two days and pushing the outmanned Confederates into military desperation.

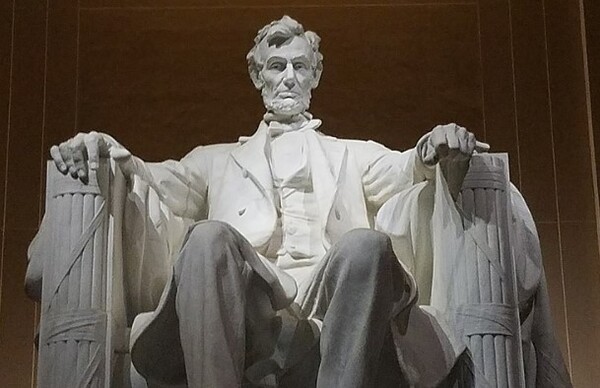

For military tacticians, historians, and President Lincoln himself, the realization became clear. After Lee’s defeat at Gettysburg, followed quickly by the fall of Vicksburg, the military tide had turned significantly in favor of the Union. Lincoln’s dream of reunifying the nation under one flag, as one United States of America, was finally within reach.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609270365559-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3035”); } }); }); }

Even so, Lincoln realized that even with the likely defeat of the Confederate Army, the long battle was not yet over, and many more American lives would be lost before the end.

Lincoln, a man who many historians call our greatest president because he presided over the reunification of the nation during its seemingly irreconcilable divide, was also a man of great sobriety. With nearly 60,000 casualties from both sides suffered at Gettysburg alone, Lincoln realized that the nation’s healing could not come from man alone.

On October 3, 1863, three months to the day after Lee’s disastrous defeat at Gettysburg, Lincoln penned a national proclamation. In it, he declared and urged Americans to set aside the fourth Thursday of November, from henceforth, as a national day of Thanksgiving.

On the third Thursday of November, November 19, 1863, Lincoln went to Gettysburg and, standing amidst the buried bodies of thousands of Union and Confederate soldiers, in a short period of two to three minutes, delivered the most famous political speech in American history.

One week later, on Thursday, November 26, 1863, the nation observed its first Thanksgiving under the presidential proclamation.

Each year since, America has paused, on that fourth Thursday, just as President Lincoln asked that we do, to give thanks.

‘); googletag.cmd.push(function () { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1609268078422-0’); }); document.write(”); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.pubads().addEventListener(‘slotRenderEnded’, function(event) { if (event.slot.getSlotElementId() == “div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”) { googletag.display(“div-hre-Americanthinker—New-3027”); } }); }); } if (publir_show_ads) { document.write(“

As a nation, the national thanksgiving list remains too long to enumerate herein. Still, we give thanks for the men and women of the American Revolution, and the Founding Fathers who gave us the U.S. Constitution; for the Americans who gave their lives in the Civil War to end the stench of slavery over the land; for the American doughboys who gave their lives in the Ardennes Forest and other areas of France; for Americans of the “Greatest Generation” who fought Nazi and Japanese tyranny in World War II; for American servicemen who fought in Korea, Vietnam, Kuwait, Iraq, and Afghanistan; for the heroes of the Civil Rights movement of the sixties, who fought to finally bring real equality to all Americans regardless of race; for the heroic first responders who charged into the collapsing Twin Towers and the burning Pentagon on 9-11; and the list goes on and on.

Hopefully, again on this Thanksgiving, we will reflect upon the sacrifices of those who have gone before us to give us the freedoms that we so often take for granted.

But as we do so, perhaps we should also reflect back on another great proclamation delivered by President Lincoln that year, 1863, which, unfortunately, has long since been forgotten and largely ignored by the nation ever since.

Five bloody Civil War battles would be fought in 1863, three won by the Union — Gettysburg and Vicksburg in July and Chattanooga in November — and two by the Confederacy — Chancellorsville in April and Chickamauga in September.

As 1862 rolled into 1863, before any of these battles unfolded, and even as he signed the Emancipation Proclamation on New Year’s Day of 1863, Lincoln knew that the nation would face great bloodshed that year.

Thus, before the first great battle, in Chancellorsville in April, Lincoln, on March 30, 1863, issued a proclamation calling for a national day of fasting and prayer.

The proclamation began by recognizing that

whereas, the Senate of the United States, devoutly recognizing the Supreme Authority and just Government of Almighty God, in all the affairs of men and of nations, has, by a resolution, requested the President to designate and set apart a day for National prayer and humiliation … it is the duty of nations as well as of men, to own their dependence upon the overruling power of God, to confess their sins and transgressions, in humble sorrow, yet with assured hope that genuine repentance will lead to mercy and pardon; and to recognize the sublime truth, announced in the Holy Scriptures and proven by all history, that those nations only are blessed whose God is the Lord.

Finally, Lincoln proclaimed that “it behooves us then, to humble ourselves before the offended Power, to confess our national sins, and to pray for clemency and forgiveness.” He then designated April 30, 1863 as a national day of fasting and prayer.

Thus, the Lincolnian proclamations of 1863, the bloodiest and most historically significant year to the United States, began in the spring with proclamation for prayer, fasting, and repentance and closed in the fall with the proclamation for Thanksgiving.

In the 160 years that have passed since both of these great proclamations, the nation seems to remember one, Thanksgiving, which is a good thing. But the other proclamation for a day of prayer, fasting, and repentance, Americans have largely forgotten.

Perhaps this year, with America divided internally more than any time since the Civil War, we might remember and practice both of Lincoln’s proclamations, with national prayer on the one end, and national Thanksgiving on the other.

That combination, both Thanksgiving and prayer seemed to help lead the nation to healing in the first Civil War.

Hopefully, by heeding Lincoln’s proclamations, by combining Prayer with Thanksgiving, we can find healing again.

Don Brown, a former U.S. Navy JAG officer, is the author of the book Travesty of Justice: The Shocking Prosecution of Lieutenant Clint Lorance, The Last Fighter Pilot: The True Story of the Final Combat Mission of World War II, and CALL SIGN EXTORTION 17: The Shootdown of SEAL Team Six and the author of 15 books on the United States military, including three national bestsellers. He is one of four former JAG officers serving on the Lorance legal team. Lorance was pardoned by President Trump in November 2019. Brown is also a former military prosecutor and a former special assistant United States attorney. He can be reached at [email protected] and on Twitter @donbrownbooks.

Image: Cathy Rowe via Wikimedia Commons, CC BY-SA 4.0 (cropped).

<!–

–>

<!– if(page_width_onload <= 479) { document.write("

“); googletag.cmd.push(function() { googletag.display(‘div-gpt-ad-1345489840937-4’); }); } –> If you experience technical problems, please write to [email protected]

FOLLOW US ON

<!–

–>

<!– _qoptions={ qacct:”p-9bKF-NgTuSFM6″ }; ![]() –> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>

–> <!—-> <!– var addthis_share = { email_template: “new_template” } –>